Toponym

The Arab place-name Hisn(i)mansur (‘Fortress Mansur’; Trk: Hüsnimansur, Hasanmansur), which was officially used until 1926, derives from the Umayyad commander Mansur bin Cavana (d. 758). In Antiquity and the Byzantine period, the toponym Perr(h)e (Grk.: Πέρρη; Pordonnium) was used. Perr(h)e (at times Antiocheia on the Taurus) was one of the four important ancient cities in the Kingdom of Commagene. The relics of Perr(h)e are now located in the district of Örenli, the former village of Pirin (also Pirun), in the north of the city of Adıyaman. The Kurdish name Semsûr was adapted from Hisnimansur. The origin of the Turkish placename Adıyaman, which has been recorded since the 17th century, is unknown.[1]

History

From Kummuh to Commagene

The toponym Commagene derives from Kummuh, a Neo-Hittite kingdom of the Iron Age located in the same area, and Commagene would retain indigenous Luwian and Hittite traditions and motifs in its architecture. The region had been part of Urartu, the proto-Armenian kingdom, under the name Sophene, which became part of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 B.C.) (…), named for the indigenous people of the area, while the actual area which would encompass the future-Commagene was known as Kummuh by the Luwians and Hittites who lived there or by the Assyrian designation, Kuinukh; nothing is known of its history at this time. Urartu declined after the 714 B.C. military campaign of the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II (r. 722-705 B.C.) which was so decisive a victory that it thoroughly destabilized the region, making it an easy mark for later Scythian invasions. After the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell in 612 B.C., the region was taken by the Medes who held it until the rise of the Achaemenid Empire c. 550 B.C.

The region’s location, and importance in trade, brought it into contact with Greek culture and this interaction would define Sophene (and later Commagene) as a cultural blend of Armenian, Greek, and Persian

influences, traditions, and religious practices. The Orontid ruling house was Zoroastrian but they were among those who encouraged the worship of the goddess Anahita, one of the most popular deities of the Early Iranian Religion which Zoroastrianism had replaced.

Under Zoroastrianism, Anahita continued in popularity as an aspect of the one, true god Ahura Mazda but, in some regions, she was worshipped as she had been in pre-Zoroastrian Persia. The temples and shrines to Anahita, and the seeming polytheism represented by shrines to other deities (such as Mithra), encouraged a comfortable rapport with Greek merchants who came from a polytheistic tradition and would have recognized aspects of their own goddesses in Anahita. This rapport, naturally, encouraged closer contact and a further blending of Armenian, Persian, and Greek cultures.

After the Achaemenid Empire fell, Sophene asserted itself as a separate kingdom, breaking away from the satrapy of Greater Armenia to form its own under the Seleucids. Its capital was the town of Carcathiocerta (modern-day Egil, Turkey) and its major urban trade center was Arsamosata (later known as Samosata, modern-day Samsat in the Adıyaman Province of Turkey). This new satrapy remained a cohesive entity under the Orontid satraps Sames I (r. 290-260 B.C.) through Ptolemaeus of Commagene (r. as satrap 201-163 B.C.) until, as noted Ptolemaeus founded Commagene.

The Kingdom of Commagene (163 B.C. – 72 C.E.) was a Hellenistic political entity, heavily influenced by Armenian and ancient Persian culture and traditions, established in southwestern Anatolia (…) by Ptolemaeus of Commagene (r. 163-130 B.C.) of the Orontid Dynasty who had formerly been satrap (governor) of the region under the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE). The Seleucid Empire had been in steady decline since it came into conflict with Rome in 190 B.C. and, by 163 B.C., no longer had the strength to maintain its earlier cohesion. Ptolemaeus seized on the weakness, declared Commagene an independent state, and became its first king.

Commagene is commonly referred to as a ‘buffer state’ between the greater powers of Armenia, Parthia, Pontos, and Rome as it maintained friendly relations with all four, favoring one over the others at different times. Its wealth, from trade and agriculture, would have made it an attractive prize for any of the larger powers of the region but the kings of Commagene managed to maintain its autonomy until 72 C.E. when it was absorbed into the Roman Empire. It is best known for the building projects of its fourth king, Antiochus I Theos (r. 70-38 B.C.), especially the monumental statuary of the site known as Nemrut Dag (also Nemrut Dagi) at Mount Nemrut. (…)

Today, the Kingdom of Commagene is remembered primarily through the monumental site of Nemrut Dagi on Mount Nemrut, (rediscovered in 1881 C.E., and a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1987 C.E.), and the various other building projects, reliefs, and statuary from the reign of Antiochus I Theos and his successors. The ruins of Antiochia ad Cragum and Aytap also remain popular tourist attractions as well as communal recreation areas, down by the water, for the local population. Nemrut Dagi, however, is the central monument to Commagene and its kings, drawing millions of visitors every year from around the world, and fulfilling the wish of Antiochus I Theos that his name should live on forever.

Excerpted from: Mark, Joshua J.: Commagene. https://www.worldhistory.org/Commagene/

Population

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 5,202 Armenians in 21 localities of the kaza Hisnimansur on the eve of the First World War, maintaining five churches and four schools for 370 children.[2]

The rural zones in the north were inhabited by Armenians, who had been Islamized at an undetermined date.

Located on the right bank of the Euphrates, Adıyaman, the kaza’s administrative seat, had a total population of 15,000 in the late 19th century, of which 6,000 were Armenians, and the remainder were Turks, Greeks and Syriacs. The inhabitants of Adıyaman mainly cultivated tobacco, cotton and hashish. There were Armenian-populated villages in the vicinity of Adıyaman: Samsat, Gantara, Kruk.

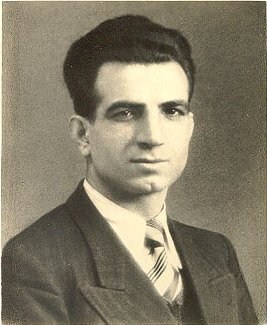

After the massacres and deportations of 1915, some Armenians settled in Adıyaman again. In 1971, 52 Armenian families lived in Adıyaman. The hero of the French resistance during the Second World War, Missak Manouchian (Manushian; 1906-1944) was born there.

24 Armenian Settlements in the Hisnimansur / Adıyaman kaza

Hisnimansur (Adıyaman, administrative seat), Bshrik (Bshrin), Bozuk (Pozuk), Gantara (Ghantara), Gavrak (Kevrak), Gyolbunar (Gyolbughnar), Zarkav, Zurna, Tavtir, Terbivk, Terbetil, Izdik, Kharfi, Kavrik (Hupek) Kiziljabunar (Kiziljabughnar), Kozan, Hayk (Hayik), Marmara, Shnabi, Orimn, Samsat, Vardana, Kilisan, Kyarkyushyen.(3)

Destruction

During the Hamidian massacres of 1895 and the massacres of Cilicia in 1909, the Armenians around Adıyaman heroically resisted the attacks by irregular gangs.

In 1915, the kaza Hüsnimansur served as a transit zone for Armenian deportees. On 14 May 1915, 400 Armenians in the kazas of Behesni and Hüsnimansur were massacred by çeteler, commanded by Haci Mehmet Ali Bey. In a 3 November telegram, the kaymakam [Nuri] informed the mutesarrıf of Malatya that “there are no more local Armenians to deport; there are only four to five households belonging to Armenian craftsmen who have come here with their families and whose conversion took place after the required religious obligations were fulfilled.” Nuri Bey also noted that there were few boys and girls who had been “placed with well-intentioned people”. “As far as the young virgins who wish to marry are concerned, the process is nearing completion.” However, the older women who also had offered to convert would not be taken into consideration, according to the kaymakam, who preferred to marry off “younger females”.[4]

“Thus”, Raymond Kévorkian concludes, “most of the Armenians allowed to remain in Adıyaman were from other regions, particularly ‘women from elsewhere who had married after converting to Islam.’ Another telegram, however, is less forthcoming about ‘how to deal with people taken into custody.’”[5]