Toponym and Administration

Located at the foot of Mount Nemrut, Kahta’s origins go back to the famous castle Arsameia (Armenian: Arshamashen) ad Nymphaios (Trk.: Kahta Çayı; Cendere). Today the Arsameia Castle is known as Eski Kale near Eski Kahta, not to be confused with Arsameia ad Euphrates, or modern-day Gerger. In the Middle Ages, Arsameia at the Nymphaios was known as Gakhtai or Kakhta. The name Gakhtai is first seen in 12th century World Chronicle of Patriarch Michael the Syrian (Syriac: ܡܺܝܟ݂ܳܐܝܶܠ ܪܰܒ݁ܳܐ, Michael the Great; Michael Syrus, or Michael the Elder, born 1126 in Melitene / Malatya)[1], which is the longest and richest surviving chronicle in the Syriac language.

The district center was moved to its current location in the 20th century.

History

In ancient times, the territory of the

later Ottoman kaza belonged to the Commagene region and kingdom.

Arsameia was founded in the third century B.C. by the Armenian king Arsames I (reigned 255-225 B.C.), ruler of Sophene (including the kingdom of Commagene, also founded by Arsames) and Armenia. “The figure of Arsames, the founder of both Arsameias, is shrouded in mystery. We get to know him thanks to the inscriptions discovered in Arsameia on the Nymphaios. Most probably, he can be identified with the king of Armenia, described by the Greek author Polyaenus, who supported Antiochus Hierax – the younger brother of King Seleucus II Callinicus. Antiochus rebelled against him, won the battle near Ankara, but eventually lost the war for power, and fled to Egypt, where he was murdered by the robbers. The construction of Arsameia’s fortress by Arsames would be justified in this light by the ongoing military activities against Seleucus.”(2)

The Seleucid Antiochos Hierax was later described by the Commagenian king Antiochos I as his ancestor. The city Arsameia ad Nymphaios was abandoned by Roman times, stones from the tombs there were used by Roman soldiers to build bridges.

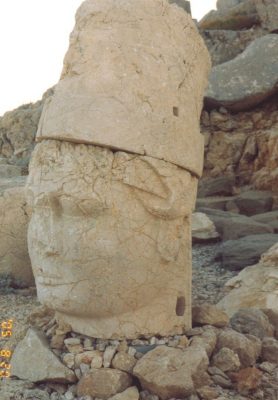

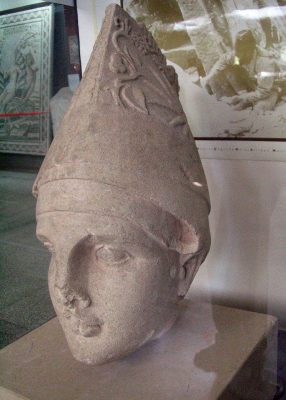

Significant cultural monuments from the Commagenian period are the tombs on Mount Nemrut, and also the hierothesia (sacred burial grounds) of Arsameia and Nymphaios (a tributary of the Euphrates) and Karakuş. The Sesönk burial mound possibly represents another hierothesion. From the Roman period are preserved, among others, the two tumuli of Sofraz and the bridge of Septimius Severus, which has the second largest bridge arch built by the Romans, 34 meters.

The present city of Kâhta is not the ancient Kâhta. The original Kâhta is located in the present village of Kocahisar (Eski Kâhta), where the fortress of Kâhta (Arsameia at Nymphaios) is also located.

The historical city of Kahta and its castle, which gave its name to the district, is the current Kocahisar village. The district center was moved to Kolik village during the republican period.

Population

The administrative seat of the kaza of same name, Kahta, was an Armenian/Kurdish-Sunni settlement at the beginning of the 20th century and is currently a Kurdish-Sunni (Kavsi) settlement. At present, Kahta is one of the districts with the most homogeneous Kurdish population in Turkey. There is no Turkish/Turkmen element except for the officers and the ethnic Turks who come to Menzil village from outside.[3]

According to the statistics of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 10,245 Armenians in 57 localities of the kaza Kahta on the eve of the First World War. They maintained 11 churches.[4]

In the administrative seat Kahta, with a total population of 4,300, more than the half was Armenian (2,250). Armenians were also numerous in the nahiyes of Şiro, Gerger, Merdesi and Zeravikan, “where more than 10,000 Armenians lived, alongside with Catholic Syriacs, Kurds, and a handful of Turks. The divergence between the Patriarchate’s population figures and the official census is astonishing here; there were more children enrolled in the Armenian schools alone than there were, according to the official count, Armenians in the kaza. Yet the summary of the deportation submitted to the mutesarif of Malatia in September 1915 contains figures matching those of the official census: this summary speaks of 791 Armenians, of whom 715 had been expelled, as well as 74 boys under ten and girls under 15 ‘without father or mother’ who were in the custody of ‘pious people’. More than 9,000 people seem to have simply evaporated without plausible explanation.”[5]

Armenian Settlements in the kaza Kahta

Kyakhta (administrative seat), Abaoun, Andam, Ashma, Bsyiki (Paizi), Arbana, Berdeso (Berteso), Bervedul (Barbados), Bimirdo, Blela, Bojukbagh, Gan (Kyan), Garn, Gomik (Komik), Gork (Komik), Dardaghan (Dardighan), Derete (Terete), Derskha, Divan (Tivan), Temsias, Terkiten, Tiltla, Tillo (Til), Tokhariz (Tokhaharis), Tomak, Khechtur (Khachatur), Khoresv, Kaghtul, Kaghter, Karatut, Karachor, Karkar (Trk. Gerger), Karghoran, Karpo, Kayikan, Kyavaz, Hajar (Hajala), Hasuntikin, Havank, Helim, Henich, Hut, Huni (Honi, Juni), Mezre, Mzragh (Mzrak’), Narenja (Narlija), Nenijanun, Shafkan, Chimrkan, Seyid-Mahmud, Sraturt, Vank (Wenk), Vankuk, Ulbish (Gurbish), Pirakh, Puturke (Petrke), Keferdish, Kikokh, Kolik (Koluk), Kordro (Kordo).

Destruction

In the autumn of 1911, the Young Turks provoked new massacres of Armenians in the village of Kahta-Mirza.[6]

As French-Armenian scholar Raymond Kévorkian summarizes with dismay, that in 1915 this “remote kaza, which saw hundreds of thousands deportees plundered or slain in the Karlik gorge, is almost a caricature of Young Turk government and Ottoman society in the Eastern vilayets. Two sub-prefects quarreled over the property of the deportees from Erzurum, who were killed soon after; an inquiry was undertaken, but only because this property was diverted from the state coffers; a Kurdish chieftain [Haci Bedri Ağa of the Reşvan tribe], who had been entrusted with the task of ‘expediting’ the deportees – that is, with the dirty work of killing them – insisted that he be given his share of the ‘pie’. Financial abuse and personal enrichment seem to have been the only crimes for which anyone could be brought before a court-martial, as if the authorities had legalized massacres in advance. A 12 December 1915 telegram would seem to indicate that while these matters were under investigation the minister of the interior [Mehmet Talat] was issuing new instructions to ‘deport’ the handful of Armenians who had so far been left in their homes: ‘In accordance with the last orders received, not a single local [Armenian] has been kept here. Similarly, not a single person come from elsewhere has been allowed to remain.’”[7]