Administration

The sancak of Kayseri comprised the three kazas of Kayseri, Incesu and Karahisar-Develi (Everek/Develi).

Toponym

Caesarea (Grk.: Καισάρεια) was historically known as Mazaka (ancient Grk.: Μάζακα; Armenian: Majak‘). The Armenian historiographer Movses of Khorene (Movses Khorenatsi) derives the toponym from Armenian ‘Mshak’, the name of a semi-legendary Armenian governor, who, according to Khorenatsi, built a dormitory here, covered it with walls and named it after him.[1]

Καππαδοκία / Cappadocia / Gamirk’

Cappadocia is a historical region in East Asia Minor, mentioned in ancient Armenian sources as Gamirk’. It is also referred to in the Bible as Gamer or Gomer. According to Movses Khorenatsi, Gamirk’ (Cappadocia) was conquered and annexed to the Armenian Kingdom by the Armenian progenitor Aram, who ordered the local population to learn Armenian. Cappadocia became a Roman province in 17 A.D., and Mazaka/Majak’ was renamed in Roman times (1st century B.C.) Caesarea in honor of Emperor Gaius Julius Octavian (Caesar Augustus).[2]

Over time, the borders of Cappadocia have changed dramatically. In the royal period (4th – 1st centuries B.C.) Cappadocia bordered Cilicia to the south (separated by the Taurus Mountains), to the southeast Commagene, to the east to the kingdoms of Sophene (Armenian: Tsopk’) and then Greater Armenia (Armenia Maior). Before the First World War, it crossed the Euphrates and Halys watershed mountains, tens of kilometers west of the Euphrates River.

A settlement of the area took place around 8000-7500 B.C., parallel to the more southern settlement area around Konya. The earliest traces of settlement date from around 6500 B.C. The Hittites also took advantage of the fertile soil as early as 1600 B.C. and cultivated crops. Later came the Phrygians and Lydians, then in the late 7th century B.C. the Medes, but they were soon replaced by the Persians. After Alexander’s campaign, Cappadocia fell to the Macedonians.

Soon, however, the Diadochi fought each other and Cappadocia was also caught up in these power struggles. In the north of Cappadocia, Mithridates I had created his own sphere of power, the later Kingdom of Pontos.

After the Battle of Ipsos in 301 B.C., power over Asia Minor was reorganized by the Diadochi. However, the Seleucid claim to power over Cappadocia was opposed by the Ariarathids, and from about 260 (or earlier) this dynasty was able to break away from the Seleucids. Cappadocia became an independent kingdom under Ariarathes I and began its own coinage. Initially still closely linked to the Seleucid dynasty, the orientation of the Ariarathids changed from 188 B.C. The crushing defeat suffered by Antiochos III against the Romans once again shifted the balance of power in Asia Minor. From now on, Pergamon, the Roman confederate, dominated politics, and the Ariarathids allied themselves with the Pergamene Attalids. In addition, the Ariarathids came into conflict with the Pontic Mithridatids, which would culminate in the Mithridatic Wars after the dynasty’s extinction.

The Ariobarzanids, who ruled Cappadocia from 95 to 36 B.C., also had a great opponent in the Pontic king Mithridates VI Eupator (“good father”) and protracted struggles for dominance. Especially the Roman generals Sulla, Lucullus and Pompeius were important “allies” for the Ariobarzanids.

Since the first king Ariarathes I (333-322 B.C.) coins were minted in Cappadocia for all kings until Archelaos (36 B.C. to 17 A.D.). The extinct volcano Erciyes Daği is the sacred mountain Argaios of antiquity and can be admired on very many coin reverses of Cappadocia.

Marcus Antonius installed Archelaos as the new king over Cappadocia in 36 B.C., bringing back stability and prosperity after the wars with Mithridates and the following hard years. Emperor Tiberius put an end to the independent kingdom in 18 A.D. and integrated it as the imperial province of Cappadocia.

Under Valens, the province was divided in 372. Caesarea remained the capital of the northern part (Cappadocia prima), Podandus became that of Cappadocia secunda in the south, but it was soon replaced by Tyana.

After the division of the empire in 395 A.D., Cappadocia became an Eastern Roman province. The Isaurians invaded Cappadocia in the 5th century A.D., the Huns in the 6th century. Khosrow I invaded Anatolia in 579 and burned Sebastea (Sivas) in Cappadocia. The Byzantine army was defeated by the Seljuks in 1071. It was followed by the Turkmen and finally the Ottomans.

Christian Population

“Since ancient times Armenians had peopled the outlying sancak of Kayseri in the southwestern part of the vilayet of Angora, which covered part of the area of the ancient province of Cappadocia. (…) The presence of an Armenian population here is attested since the third and fourth centuries of our epoch. It increased over time: after the Arabs conquered part of Asia Minor, Armenian colonists were settled here by the Byzantines in order to strengthen the military marches of the Taurus. On the eve of the First World War, there were still 31 towns and villages inhabited by more than 52,000 Armenians in this sancak. These possessed 40 churches, seven monasteries, and 56 schools with an overall enrolment of 7,119. (…)

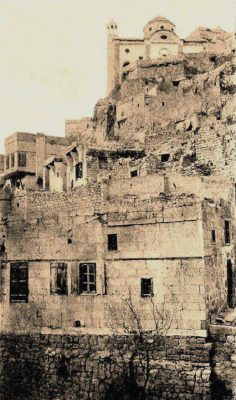

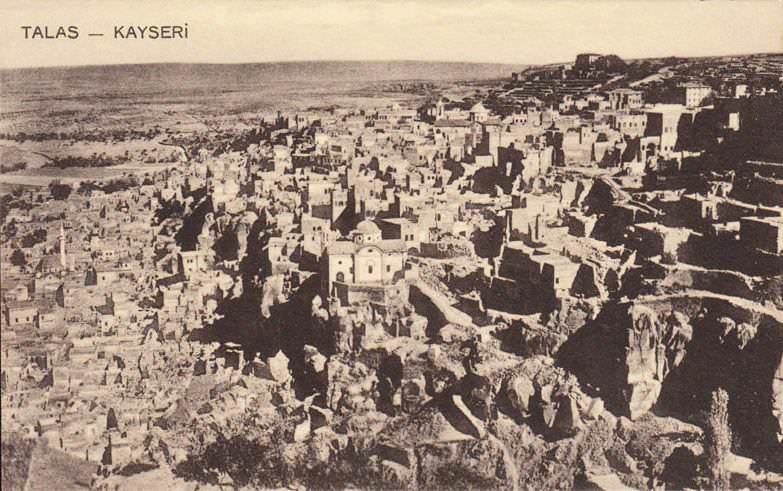

Five kilometers southwest of Cesarea, the village of Talas, albeit in the decline in the early twentieth century, still had an Armenian population of 1,894, representing 42 per cent of the total population. (…) The village of Derevank (310 Armenians), just northwest of Talas, dominated the entry to a valley in which there lay a string of Armenian villages: Tavlusun (pop. 115), Germir (pop. 365), Balages (pop. 923) – on the outskirts of which lay the immense monastery of St. Daniel, established in the mid-eleventh century and demolished a few days after all inhabitants of Balages were deported – Mancesen (pop. 386), Nirze and the adjoining village of Darsiak (pop. 835), with the monastery of St. Gregory, founded in 1206, a quarter of an hour away. The villages of Muncusun (pop. 1,669) and Evkere/Gasi (pop. 2,154) closed off the northwestern extremity of the valley that began above Talas, with the famous monastery of St. Garabed, the region’s most important spiritual and educational center and also seat of the diocese’s archbishop since the twelfth century. The last of these villages, Erkelet (pop. 300), lay in the northern part of the kaza. Thus, there was a non-negligible rural Armenian population, particularly in the kaza of Kayseri.”[3]

Greeks have lived in the area since ancient times. The Greek Orthodox Diocese of Cesarea consisted of 52 communities with 34,000 inhabitants, who have “suffered greatly economically owing to the mobilization and the boycott. The authorities contributed by persecutions towards the oppression of the Christians, imposing arbitrary taxes and forced subscriptions for the needs of the State and the Army, thus rendering the situation of its Christian inhabitants an extremely precarious one.”[4]

The Greek Orthodox survivors were forcibly resettled in Greece at the beginning of the 1920s, although they spoke Turkish in most of their daily lives. The Greek dialect of this region, Cappadocian, is now considered extinct.

Destruction

In the first half of March 1915 Armenian notables were arrested in Everek. Many of the arrested died under torture in the konak [official residence, seat of local goverment] of Everek.[5] On 13 June 1915, the arrests of Armenian notables of Talas began. Soon afterwards, they were shot at Gemerek.[6] On 15 June 1915, eleven members of the local Armenian elite of Kayseri were hanged at the Kömür Bazaar’s square. These executions were followed by 857 more of individuals condemned to death by the military tribunal at Kayseri.[7] In the beginning of July the male Armenian population of Derevank and in all the Armenian villages in the valley was systematically arrested and then executed.[8] In the second half of July, the arrests of men over the age of fourteen became systematic. They were sent out of town each night and executed under the supervision of the captain of the gendarmerie and the head of the bandits of Kayseri’s Special Organization, Gübgüzade Sureya Bey.[9]

From 13 August, some 20,000 Armenians from Kayseri and Talas were deported in several convoys to the Syrian Desert via İncesu, Develi, Niğde, Bor, and Ulukışla under the personal supervision of Yakub Cemil Bey, the CUP delegate in the province. The first convoy from Kayseri was made up of the remaining Armenians from the peripheral district.[10] After the males were exterminated, 13,000 Armenians from the kaza of Everek were deported to Syria on 18 August 1915 under the supervision of the kaymakam Salih Zeki; around 600 arrive in Aleppo, and 400 arrive in Damascus.[11] On 18, 28 and 29 August, the Armenians of Talas were deported to Syria in three convoys.[12]

“Of all people implicated in the atrocities inflicted on the Armenian population of the sancak of Kayseri, only Şakir Bey was indicted by the Istanbul court-martial in 1920. He was ultimately acquitted.”[13]