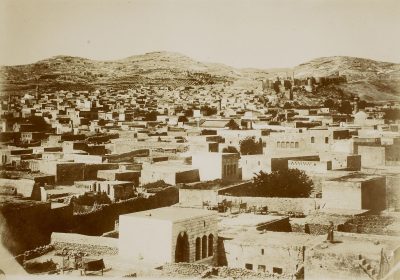

The homonymous administrative seat of the kaza, Urfa, is one of the oldest human settlements and a crossroad of civilizations, known under many toponyms.

Christian Population

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, the Armenian pre-war population of the kaza of 36,448 lived in ten localities, maintaining six monasteries and 20 (?) schools.[1] Most Armenians of the kaza resided in the administrative center Urfa. “There were only a few Armenians in the northern plain of Mesopotamia, in Garmuc [Dağeteği], an hour and a half northeast of Urfa (pop. 5,000), Mankush (60 households), Tlbaşar (100 families), and in the nahie of Bozova, in Hoghin and Hovig, whose Turkish-speaking inhabitants were winegrowers or raised silkworms.”[2]

According to Agha Petros list there lived 7,200 Syriacs in the city of Urfa, and a further 8,000 lived in ten outlying villages. “Some of these villages were very large – Roum Kale [Rumkale], Serudj [Suruc], Harran, and Biredjik [Birecik] had close to 2,000 Syriac residents each. Tfinkdji noted 200 Chaldean residents with 2 priests, 1 church, and 2 schools.”[3]

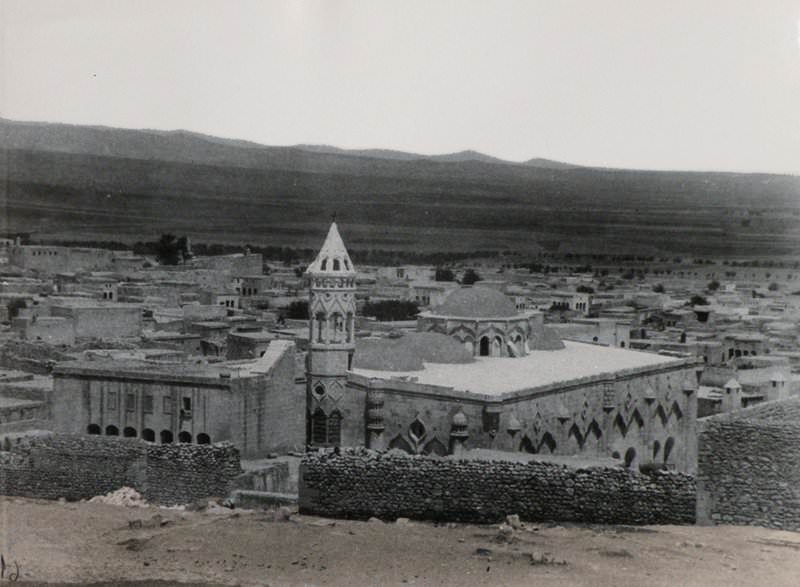

City of Urfa / ܐܘܪܗܝ – Urhoy / Ուռհա – Urha / Ἔδεσσα – Edessa

“Mother of many children”: The Toponym

Situated at the crossroads of ancient land trade routes and on a fertile plain, the biblical northern Mesopotamian city with many names looks back on an eventful history spanning four millennia. For Aramaic-speaking Christians it is still called Urhoy, which became Urha in Armenian. The Greek general Seleucus I Nicator (the Victorious; 358-281 B.C.), the successor of Alexander the Great and founder of the Seleucid dynasty, gave it the name of the first capital of Macedonia, Macedonian capital, Ἔδεσσα – Edessa. Under this name it was still known to the crusaders in the Middle Ages, when Edessa formed a Frankish county.

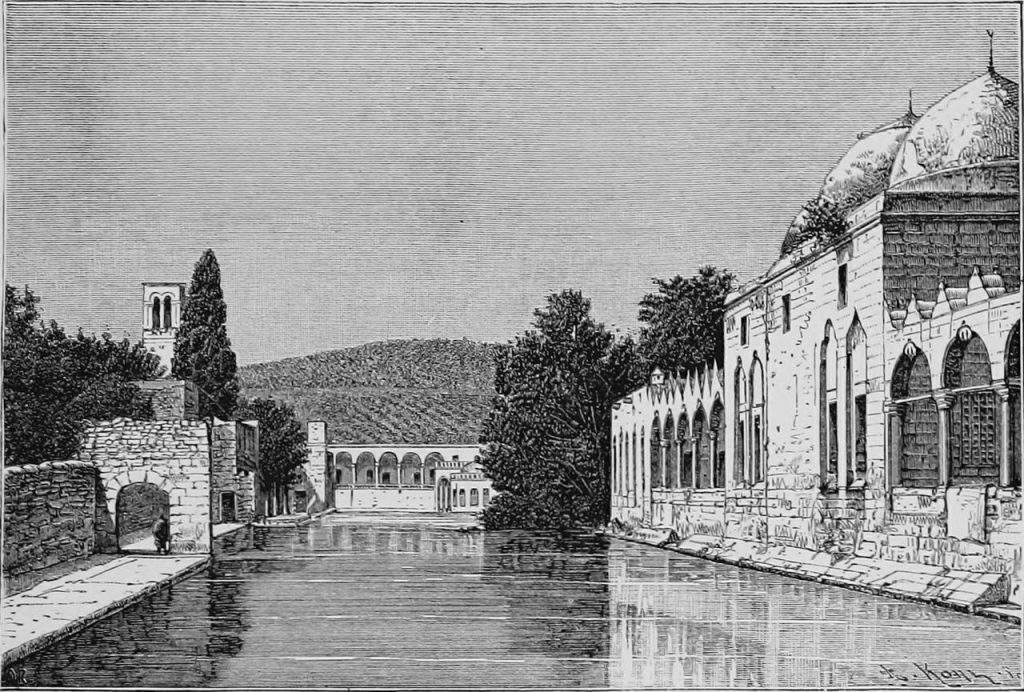

During the rule of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 B.C.) the city was named Callirrhoe or Antiochia on the Callirhoe (Ancient Greek: Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Καλλιρρόης). During Byzantine rule it was named Justinopolis.

Urhoy/Edessa officially became Urfa when it was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1637. Şanlı means ‘great, glorious, dignified’ in Turkish, and Urfa was officially renamed Şanlıurfa (‘Urfa the Glorious’) by the Turkish Grand National Assembly in 1984, in recognition of the local resistance in the Turkish War of Independence. The title was granted following repeated requests by the city’s members of parliament, eager to receive a title similar to those given to neighbouring cities Gazi (Veteran) Antep and Kahraman (Heroic) Maraş.

Population

There were three Christian communities in Urfa: Syriac (7,200), Armenian, and Latin. On the eve of the First World War, 25,000 to 30,000 Armenians resided in the city of Urfa[4], representing a third of the overall population of 60,000.

There existed also a small but ancient Jewish community in Urfa, with a population of about 1,000 by the 19th century. Most of the Jews emigrated in 1896, fleeing the Hamidian massacres, and settling mainly in Aleppo, Tiberias and Jerusalem.

Raymond Kévorkian: Bridge between Mesopotamia and Asia Minor

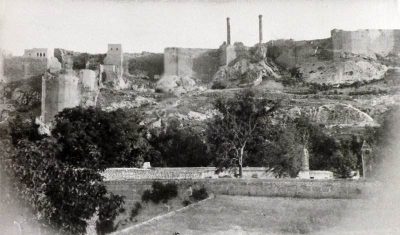

“The ancient city of Edessa was long a political and cultural center of the first importance. A sort of bridge between Mesopotamia and Asia Minor, it was inhabited by very diverse populations. The Armenians and Syriacs who lived here still shared early in the twentieth century an attachment to the Near Eastern cultural heritage, which they zealously propagated. The Armenians arrived in the region of Edessa very late – that is, early in the eleventh century. (…) The city itself lay in a vast, fertile plain, except for the Armenian quarter, most of which rose, level after level, up the slopes of Mt. Telfedur in the northern part of the city. Overlooking the lower part of the Armenian quarter was the Cathedral of the Holy Mother of God, the archbishopric, and the Armenian middle school.

Commercial activity in Urfa, the economic center of Upper Mesopotamia, was then largely dominated by the Armenians, who were also active in certain craft guilds, such as those of stonecutters, architects, boot-makers, copper tinners, goldsmiths, rug weavers, and blacksmiths. The fertility of the surrounding plain, irrigated by the Berik, made it possible to cultivate immense vineyards and orchards, as well as cereals and cotton. There were many thriving industries centered on weaving, the production of cotton prints, and dying.”[5]

History

The history of Urfa is recorded from the fourth century B.C., but may date back at least to 9000 B.C., when there is ample evidence for the surrounding sites at Duru, Harran and Nevali Cori.

Neolithic

Urfa shares the Balikh River Valley region with two other significant Neolithic sites at Nevalı Çori and Göbekli Tepe. The city originated circa 9000 BCE as a PPNA Neolithic site located near Abraham’s Pool (Site Name: Balıklıgöl). It was part of a network of first settlements spanning West Asia where agriculture began. It was here that the life-sized limestone “Urfa Man” statue was found during an excavation and is now on display at the Şanlıurfa Archaeology and Mosaic Museum. The Urfa Man resembles both carvings at nearby Göbekli Tepe and statues found at ‘Ain Ghazal. The village at Balıklıgöl was followed by a string of four PPNB villages on four hilltops at the Gürcütepe site. Beginning in 6200 B.C. small Halaf culture villages began to appear in the Balikh Valley. The typical Halaf village is 2ha with a population of 500 people surrounded by agricultural fields. By 5000 B.C. the entire valley was densely filled. Two of these villages would become the nuclei for the major cities of Urfa and Harran.

Bronze Age

The Uruk period expansion triggered the formation of cities on the upper Euphrates. In a process known as secondary urbanization, which began around 3200 B.C., countryside villages emptied out and were replaced by cities. The rise of Urfa and Harran mirror the rise of Ebla as all three were driven by the same underlying economic expansion of Uruk. By the Early Bronze Age (2900–2600 B.C.) Urfa had grown into a walled city of 200ha. This city is located at the archeological site Kazane Tepe adjacent to modern Urfa. There is a tentative, yet unproven identification of ancient Urfa (Kazane Tepe) with the city of Urshu. Urshu is mentioned in the Ebla archives as a kingdom joined in political alliance with Ebla by marriage through a princess of the royal house. Ancient Urfa continued as a sovereign Bronze Age city-state until its annexation into the Akkadian Empire and its successor the Neo-Sumerian Empire. After the fall of Ur it was again independent for a time until it fell to the Old Assyrian Empire and was abandoned in the Amorite expansion in 1800 B.C.

Biblical history

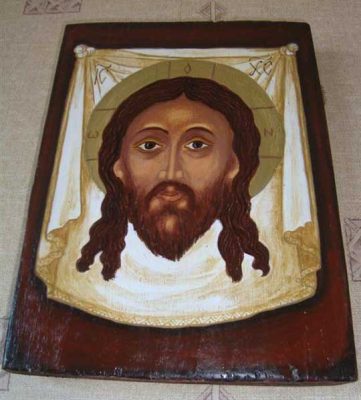

Jews, Christians and Muslims alike revere Urfa because the Jewish progenitor Abraham (Ibrahim) and the prophet Job are said to have lived here. According to Muslim belief, Urfa is Abraham’s birthplace and the fifth most important city in Islam. Christians know Urfa as the oldest Christian city-state: according to their tradition, the Aramaic ruler Abgar V. Ukkama (‘the black one’; 9-46 AD) is said to have been in correspondence with Jesus and to have asked him for healing. The apostles Thomas and Thaddeus were sent for this purpose. According to Syriac Orthodox tradition, Thomas is even considered the founder of that ancient church that is so closely interconnected with the history of Urfa. According to their tradition, the bones of the apostle were transferred from Parthia or India to Edessa and buried there. Closely related to the Abgar legend is the tradition of the mandylion, which is linked to the image of Christ in Edessa. According to an earlier tradition, the mandylion was painted by the messenger of King Abgar, and according to a later tradition, the mandylion was not made by human hands, but by direct transfer of the face onto a cloth (“Acheiro-poieton”). A copy of the miraculous portrait cloth of Jesus is now in the Vatican, another since the 14th century in Genoa.

Syriac history

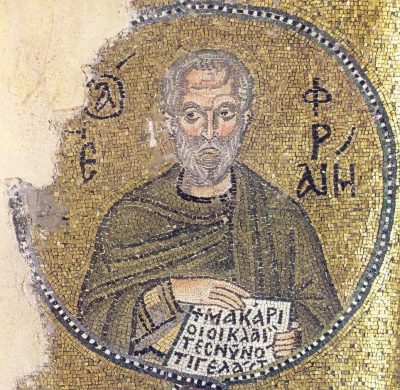

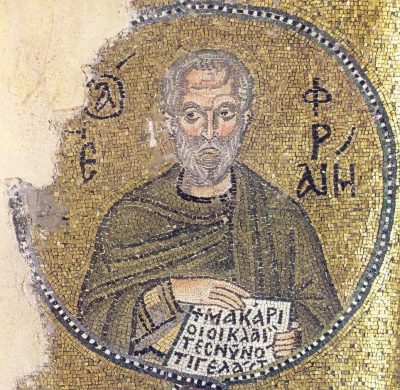

In late ancient and early medieval times, Urhoy/Edessa was a center of Syro-Aramaic learning and spiritual life. The late ancient saint, teacher, deacon, writer and church teacher Ephräm the Syriac (also Afrem, Ephraem, Ephraim, Ephrem; Aramaic ܡܪܝ ܐܦܪܝܡ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ Mor Aphrêm Sûryoyo; * c. 306 in Nisibis, today Nusaybin; † 9 June 373 in Edessa) taught as an ascetic in Nisibis until Emperor Jovian had to surrender the city to the Persians in 363. Since then he lived near the city of Edessa.

He is considered the founder of the school of the Persians and, along with his older contemporary Aphrahat, one of the greatest theologians of the Syriac church.

At times, Melkite and East and West Syriac bishops officiated side by side in Edessa. One of the most famous was the historian, bishop and churchfather Jacob Baradaeus of Edessa (Grk.: Βαραδαι̑ος, Arabic: مار يعقوب البرادعي, Syriac: ܝܥܩܘܒ ܒܘܪܕܥܝܐ), also known as Mor Ya`qub Burdono, Jacob Bar-Addai, or Jacob bar Theophilus (†578). His missionary efforts helped establish the Syriac Orthodox Church, also named ‘Jacobite’ Church after its eponymous founder, and ensured its survival despite persecution.

Urfa is also the birthplace of the Melkite Theodore Abū Qurra († c. 830), one of the earliest Christian thinkers in Arabic.

Armenian history

For the Armenians, Urfa is considered a holy place since it is believed that the Armenian alphabet was invented there.

City of Edessa

Although the site of Urfa has been inhabited since prehistoric times, the modern city was founded in 304 B.C. by Seleucus I Nicator and named after the ancient capital of Macedonia. In the late 2nd century, as the Seleucid dynasty disintegrated, it became the capital of the Arab Nabataean Abgar dynasty, which was successively Parthian, Aramean/Syriac kingdom Osroene, Armenian, and Roman client state and eventually a Roman province. Its location on the eastern frontier of the Empire meant it was frequently conquered during periods when the Byzantine central government was weak, and for centuries, it was alternately conquered by Arab, Byzantine, Armenian, Turkish rulers. In 1098, the Crusader Baldwin of Boulogne induced the final Armenian ruler to adopt him and then seized power, establishing the first Crusader State known as the County of Edessa and imposing Latin Christianity on the Greek Orthodox, Assyrian Church of the East and Armenian Apostolic majority of the population.

Age of Islam

Islam first arrived in Urfa around 638 A.D., when the region surrendered to the Rashidun army without resisting, and became a significant presence under the Ayyubids (see: Saladin Ayubbi), Seljuks.

At the end of the 11th century, crusaders seized the multi-ethnic city-state of Edessa, but lost it to the Turkish Abbasid general and Muslim ruler of Mosul, Imad ul-din Zengi (also Zengui; d. 1146), under Count Jocelyn de Courtenay the Younger, who was weak in morals and character. Zengi began the siege of the leaderless city in Courtenay’s absence on 30 November 1144. When it was forced to surrender on 23 December of the same year, Zengi gave it up to plunder for three days. Mainly the Frankish or Catholic population fell victim to massacres and enslavement.

The fall of Christian Edessa inspired one of the most outstanding contemporary Armenian spiritual poets, Catholicos Nerses IV Shnorhali (‘the Gracious’) Pahlavuni, to write an elegy (completed in 1145). In this long lament, consisting of 1070 double-spaced rhymed stanzas, Nerses depicts Edessa’s fall as a tragedy for all Christendom, caused by “the abundance of his sins and betrayal by unfaithful hands.” He draws on accounts from participants in the fighting and siege, including his nephew Apirat. The Urha of the Armenians and Syriacs, “the mother of many children,” becomes in Nerse’s elegy a mourning widow and ‘mistress’ who, seeking help, implores her sisters, the metropolises of Christendom at that time: Jerusalem and Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria and Antioch.

The subsequent Second Crusade failed to recapture the city. Subsequently, Urfa was ruled by Zengids, Ayyubids, Sultanate of Rum, Ilkhanids, Memluks, Akkoyunlu and Safavids before Ottoman conquest in 1516. Under the Ottomans the area became a center of trade in cotton, leather, and jewellery.

Destruction

“A Great Holocaust”: The Massacre of 28/29 December 1895

Since September 1895, in North American and European publications, the biblical Greek term holocaust (“whole-burning sacrifice”) became a synonym for Ottoman persecutions of Christians. One of the first to use it in her correspondence was the American teacher and evangelical missionary Corinna Shattuck (1848-1910). Shattuck had taught at a girls’ school in Urfa since 1892 and helped establish a school for the blind there in 1902. As an eyewitness, she reported in a letter dated 7 January 1896 and under the immediate impression of the massacre of 28 December 1895:

“ On Saturday, December 28th, the firing of a few guns in the Moslem quarter south of us proved the signal. Immediately an immense multitude gathered on the hill back of our house. The guards in the street east of us went to meet the people, fired a few shots over their heads, and then allowed the mass of wild humanity, thirsty for blood, to pass into the city and begin their work. The horrid work continued until dark. Three soldiers kept the mob from entering our street, constantly proclaiming: ‘It is the house of a foreigner, and it is forbidden to touch her.’ We find by count that our ‘shadow’ covered 17 houses and 240 people. The mob came as far as to enter our girls’ schoolrooms in the churchyard, and they broke open the third door below us on the street and plundered the house. I saw one man beaten and then thrown down on the roof just opposite to me on the other side of the street.

The Syrians and Roman Catholics were also spared. All other Christians suffered complete loss of ail home furnishings, and some houses were burned. The number of killed cannot be less than 3,500 and may reach 4,000. Of these it is estimated that 1,500 perished in the great Gregorian church [cathedral]. On Saturday that portion of the city was hardly touched, and great numbers of Armenians flocked to the church for safety that night. Sunday morning the work began again at daybreak, and when the people reached the church the soldiers broke open the doors. Then entering, they began a butchery which became a great holocaust. It was participated in by many classes of Moslems. For two days the air of the city was unendurable; then began the clearing up. During two days we saw constantly men lugging sacks filled With bones and ashes. The dragging off of 1,500 bodies for burial in trenches was more quickly completed, some being taken on animals. The last work of all has been the clearing of the wells. From one very large well it is said that 60 bodies were taken. It is well authenticated that 20 bodies were taken from another well. About 300 persons escaped from the church by way of the roof, which was reached by a narrow staircase on the inside. Shortly after noon on Sunday, some fifteen or more of the prominent citizens and government officials (not including the Mutessarif, or the military commander), preceded by a military band and mounted guard, made a grand parade of the city. They entered our yard, and, speaking with me from the veranda, they assured me of perfect safety and begged me not to be alarmed, as it was ‘nothing that pertained to me.’ I very quickly went into my room.”[6]

The Scottish historian and biographer of Mustafa Kemal, Lord Patrick Balfour, 3rd Baron Kinross (1904-1976) mentioned an almost double number of Armenian victims, 8,000:

“Cruellest and most ruinous of all were the massacres at Urfa, were the Armenian Christians numbered a third of the total population. Here in December, 1895, after a two-months siege of their quarter, the leading Armenians assembled in their cathedral, where they drew up a statement requesting Turkish official protection. Promising this, the Turkish officer in charge surrounded the cathedral with troops. Then a large body of them, with a mob in their wake, rushed through the Armenian quarter, where they plundered all houses and slaughtered all adult males above a certain age. When a large group of young Armenians were brought before a sheikh, he had them thrown down on their backs and held by their hands and feet. Then, in the words of an observer, he recited verses of the koran and ‘cut their throats after the Mecca rite scarifying sheep’.

When the bugle blast ended the day’s operations some three thousand refugees poured into the cathedral, hoping for sanctuary. But the next morning – a Sunday – a fanatical mob swarmed into the church in an orgy of slaughter, rifling its shrines with cries of ‘Call upon Christ to prove Himself a greater prophet than Mohammed.’ Then they amassed a large pile of straw matting, which they spread over the litter of corpses and set alight with thirty cans of petroleum. The woodwork of the gallery where a crowd of women and children crouched, wailing with terror, caught fire, and all perished in the flames. Punctiliously, at three-thirty in the afternoon the bugle blew once more, and the Moslems officials proceeded around the Armenian quarter to proclaim that the massacres were over. They had wiped out 126 complete families, without a woman or a baby surviving, and the total casualties on the town, including those slaughtered in the cathedral, amounted to eight thousand dead.”[7]

In Urfa and its environs, Kurdish irregulars of the so-called Hamidiye cavalry slaughtered 13,000 Syriacs.

The massacres of 1985/6 triggered spontaneous relief efforts in Europe. The “largest German aid organization by far” was the Hülfsbund für christlichen Liebeswerk im Orient (based in Bad Homburg), which is still active in Lebanon and Armenia and was originally close to the German revivalist movement. Before the First World War, the Hülfsbund maintained “five main stations and 29 subsidiary stations in Maraş and four other places, in whose orphanages about 1,500 children were accommodated and in whose schools more than 3,300 children were taught by 109 teachers. The Hülfsbund consisted of 26 missionaries”.[8]

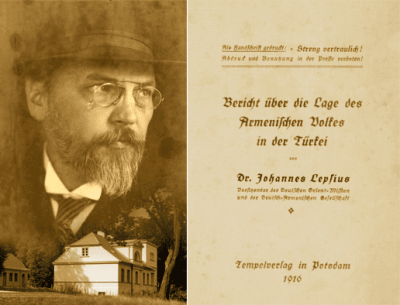

The German Protestant theologian and missionary Dr. Johannes Lepsius (1858-1926) had already founded the German Oriental Mission (DOM) in 1886, but since 1895 he placed it entirely in the service of impoverished Armenian survivors, mostly women and orphans. J. Lepsius founded a hospital, an orphanage and a carpet weaving factory called ‘Masbane’ (‘soap factory’, according to the former function of the building) in Urfa for the impoverished survivors; the orphanage and carpet factory were run by the German teacher and missionary Franz Hugo Eckart (1873-1919), assisted by his younger brother Bruno (d. 1945). From 1903, all charitable institutions were under the overall direction of the Danish missionary Karen Jeppe (1876-1935), who made a name for herself during and after the First World War as a rescuer of numerous Armenian children. In 1917, Karen Jeppe, suffering from typhus, left Turkey, but continued her work in 1921 as an official representative of the League of Nations in neighboring Syria; she was buried in the Armenian cemetery in Aleppo.

In 1920, the Swiss German Gertrud Vischer-Oeri described the beginnings and activities of the German Orient Mission (Deutsche Orient-Mission) in Urfa in her diary entries as follows:

“In a huge Chan (caravanserai) orphans, probably well over a hundred, were taken in, under the direction of the Danish Karen Jeppe and two elderly Armenian house-parents. A carpet weaving factory was established in the city, which gave work to many Armenian women and girls according to old Persian patterns under the direction of Mr. Eckart and artistic pattern drawing by his brother [Bruno Eckart]. Then a hospital was also established in the city, where a Swiss woman, Dr. Zürcher, worked. After her came Dr. Christ from Basel, whose wife, however, became ill after a few years. Brother Jakob Künzler, who was trained as a carpenter, worked with Dr. Christ. He later trained as a nurse in the deacon’s house in the Äschenvorstadt and was very valuable for the work in the hospital and for practical work. He was also the one who inspired Dr. Andreas Vischer for Urfa during his vacation in 1905.” [9]

1915-1918

During the First World War, Urfa was a site of the Armenian and Syriac genocides, beginning in August 1915. By the end of the war, the entire Christian population had been killed, had fled, or was in hiding.

Throughout the summer of 1915, Urfa was effectively transformed into a transit center for ten of thousands of deportees[10], whose misery and horror reports had given the Armenian inhabitants of Urfa a clear picture of the fate that lay ahead of them. In mid-June, around 2,000 deportees from Zeytun had passed through Urfa, whom the city’s inhabitants had undertaken to assist. “In the following weeks, Armenians in a state beggaring description flooded into the city. They were put in particular in a large khan located at the exit from the city on the road to Aleppo, which all the caravans had to take; the courtyard of this khan was slowly transformed into an open-air morgue. A few of these deportees managed, after the fall of the Armenian neighborhoods, to hide in the city, but they were late dispatched southward after a surprise roundup organized in June 1916 by the local authorities.”[11]

In Urfa, „(m)assive arrests began on 8 June [1915]. Sixteen notables and high-ranking officials were apprehended: Garabed Izmirlian, the president of the diocesan council; Soghomon Knajian; Khosrov Dadian, the city’s treasurer; Arush Sarafian; Arush Kaghtalian; Kevork Der Bedrosian; and Hagop and Nazar Kulahian; Sarkis Ejzaji; Yesekiel Boyajian; Garabed Kataroyan; and Kazanji Kambur, Mgrdich Yotneghperian, disguised as a Bedouin, succeeded in making his way into the prison where these men were being held and suggested carrying out an operation to free them, but all refused, fearing that such an action would bring an a general massacre. (…) The 16 notables (…) were tortured and then deported to Rakka on the 13th; their families joined them there a few days later. While some were brought back to Urfa around 26/27 June, the others were liquidated one hour from Rakka in a place known as Cir Tosun.”[12]

Further arrests of hundreds of Armenians followed. On 28 July, all prisoners were transferred to Diyarbekir, among them the primate of Urfa, Artavazd Kalenderian. These men were massacred on 30 July on the road to Diyarbekir in a place near Urfa known as Şeytan Deresı.[13] This massacre was conducted by two high-ranking officers of the Special Organization (Teşkilat-I Mahsusa), Lieutenant-Colonel Halil Bey [Kut], the uncle of War Minister Enver, and Çerkez Ahmet (Ahmed). Their next operation followed on 10 August 1915, when a battalion of the Special Organization under Halil’s order “set out to execute the 1,500 Armenian and Syriac worker-soldiers in two amele taburis working in Karaköprü and Kudeme, in the vicinity of Urfa. After surrounding the camp in Karaköprü, the çetes tied these men up, lined them up in front of ditches that had been dug in advance, and shot them. When they attacked the camp in Kudeme the next day, however, a number of worker-soldiers defended themselves with their tools or their bare hands. Some even managed to seize their executioners’ weapons and take up positions on a promontory, where they put up three days’ resistance before committing suicide. Two survivors from these amele taburis, the brothers Sarkis and Krikor Daraghjian of the Sanderchonts family, were able to return to Urfa and inform the population about the massacres (…).”[14]

The authorities killed also “as many as possible of the captive ‘Syriacs, Chaldeans, Jacobites, and Armenian Catholics.’ Among the dead ere the Syriac priest Hana Kandalaft and the Syriac monk Efram. Other clerics were put under house arrest.

Vartabed Vartan, the Armenian Catholic leader, hid in the house of a Muslim friend. When he was caught, he was sent away to a prison in Adana, where he was sentenced to death. He appealed for a new trial and was sentenced to 101 years imprisonment, which was reduced to 15 years. He was hanged on the order of the local governor after the armistice had been signed at the end of the war, only two days before the English and French troops arrived and took control.”[15]

On 23 August 1915 the highest Ottoman official ordered that all Armenians be deported from Urfa. Since the Armenians knew very well what that meant, “they refused and prepared to defend themselves in their homes. A siege of the Armenian quarter began, and a final week-long battle began on September 23.”[16]

On the opposite side were Ottoman professional soldiers, supported in the case of Urfa by the German Major Count Eberhard Wolffskeel von Reichenberg, whose participation was indirectly criticized by the German consul to Aleppo, Walter Rössler, in a letter of 25 October 1915 to his ambassador: “The fact that Count Wolffskeel accompanied General Fakhri Pasha will also have fed the suspicion that Turkey was acting under German advice and influence. I may add that Count Wolffskeel also accompanied Fakhri Pasha in the military action against the insurgents at Suediye [Musa Ler] at the end of September. To Your Excellency’s high consideration I therefore obediently submit whether it is expedient for a German officer to take part in an expedition against an internal Turkish enemy.“[17]

„On 13 October, after they had been pounded for 24 hours, the Turkish troops launched a violent assault, gaining control of a number of Armenian positions. A second general offensive launched on 19 October left most of the Armenian neighborhoods in the assailants’ hands. By the evening of 23 October, after 25 days of fighting, all the Armenian positions had been taken by the army. Most of the defenders had either died in combat or committed suicide, beginning with Mgrdich Vorneghperian, who shot himself in the head, after the last bastion fell.”[18]

The letters of the German besieger Wolffskeel, who came from old Franconian nobility, were characterized by strong anti-Armenian prejudices and were first quoted in excerpts by the Austrian contemporary historian Wolfdieter Bihl in 1985[19] and edited for the first time by the German-American historian Hilmar Kaiser together with the Swiss genocide researcher Dominick Schaller in 2001[20]. In Urfa, a battle was raging from house to house, Wolffskeel wrote to his wife on 12 October 1915. It would take another 14 days “until we have broken down the gang.” But only four days later his work was completed. Now came the “unpleasant part” with the deportation and the courts martial, which, however, belonged to the “domestic Turkish affairs”. Wolffskeel did not see any need for humanitarian action in favor of the Armenian population of Urfa, although he was precisely informed about the crimes committed against the Armenians by the German missionary Franz Eckart and was able to get a clear picture of the extent of the destruction himself after taking the Armenian quarter:

“I walked through the city on the day I took it. But the situation looked bad. Shot up, burned down or still burning houses, everywhere in the streets and in the houses dead in quantities, partly half or completely charred. Without a cigarette, one could not go through at all. These half-savages with the fanatical, black-bearded distorted faces make a much more unpleasant impression even in death than the fallen on a battlefield. There is also the horror of civil war. It looked especially bad in one of the Armenian churches. (…)

Here and there I see the director of the German factory, Mr. Eckart, a pleasant, clever man who has lived here for 20 years and can judge the conditions quite correctly. The upcoming times will be quite difficult not only for him, but for all of Urfa. There are no more workers. All, but also all craftsmen were Armenians, the Turks were at most engaged in some agriculture. Now, when all Armenians are deported, all industrial activity will cease. There are no more tailors, no blacksmiths, in short nothing.”[21]

Wolffskeel was satisfied that the court martial of the “Armenian uprising” in Urfa would take place with the participation of his Ottoman superior Fahri Bey, whom Wolffskeel qualified in a letter to his wife of 19 October 1915 as a “decent character” and a “conscientious and humane man”.[22] Fahri demanded from Franz Eckart that all Armenians still present in the carpet factory had to leave it and assured them of immunity from punishment in the event of their departure. Breaking their word, Fahri’s soldiers soon murdered on a hill those Armenians who had been delivered by the German missionaries in good faith.

1919-1920

The British occupation of the city of Urfa started de facto on 7 March 1919 and officially de jure as of 24 March 1919, and lasted until 30 October 1919. French forces took over the next day and lasted until 11 April 1920, when they were defeated by local resistance forces before the formal declaration of the Republic of Turkey on 23 April 1920.

The French retreat from the city of Urfa was conducted under an agreement reached between the occupying forces and the representatives of the local forces, commanded by Captain Ali Saip Bey assigned from Ankara. The withdrawal was meant to take place peacefully, but was disrupted by an ambush on the French units by irregular Kuva-yi Milliye on the way to Syria, leading to at least 296 casualties among the French:

“The French left [Urfa] early on April 11 [1920], with sixty camels and thirty horses. They met their fate nine miles out, at Sebeke Pass. (…) Garnet Woodward, a British NER [Near East Relief] worker who accompanied the colum, (…) reported that the French attempted to surrender but were shot down by Kurds and Turks, who proceeded to finish off the wounded. Gendarmes sent from Urfa eventually ended the killing and saved some of the soldiers. Between 50 and 161 troopers, most of them Muslim Algerians and Tunisians, survived and were brought back to Urfa. Three hundred and more soldiers died. (…) The French blamed the Armenians for the debacle at Urfa, aggravating Franco-Armenian relations.”[23]

The last Neo-Aramaic Christians (Syriacs) left in 1924 and fled to Aleppo (where they settled in a place that was later called Hay al-Suryan ‘The Syriac Quarter’).

Gertrud Vischer-Oeri: Memories of Urfa (Diary)

The Swiss Gertrud Vischer-Oeri was the wife of Dr. Andreas Oeri, who ran the hospital of the German Orient Mission in Urfa from spring 1919 to summer 1920. For her children who remained in Switzerland, G. Vischer-Oeri recorded her experiences and impressions from Urfa during this period. Urfa, which officially belonged to the French occupation area, was besieged by Kemalist nationalist forces, but at times also attacked by Kurdish and Arab irregulars. Especially the Christian survivors of the genocide in World War I who had returned to Urfa soon had to fear for their safety again. The following excerpts from G. Vischer-Oeri’s records illustrate this:

16 August 1919: (…) It was a difficult decision for me to go to the destroyed Armenian quarter for the first time. (…) First we paid a visit to Mrs. Vartuhi [Varduhi], the wife of our former pharmacist Abraham. (…) Mrs. Abraham was deported with her daughters and the youngest son, but later she escaped to Aleppo, where she lived for 5 years in great poverty, but without losing any of her 6 children. Two sons, who had been in American schools, were able to return to their mother. The 4 oldest children gradually found work in Aleppo, through which they at least earned their living. About 4 months ago, Vartuhi Khanum returned to her house in Urfa, which is one of the few Armenian houses that was not destroyed because it was adjacent to the Turkish quarter. But how different it looks now in this house than 5 years ago, when we were last there. At that time, the Abrahams were wealthy people who were very well furnished by local standards. Now everything is empty, there is no carpet on the floor, hardly any bedding, hardly any kitchen utensils. The 2 older daughters are employed by the American relief organization [Near East Relief] as nurses and teachers, one son has remained in Aleppo, where he now has a decent job. But his and the family’s great wish is that he should still be allowed to study medicine; he had already started at that time. (…)

(…)

19 August 1919: (…) Towards the mid of October [1919], rumors were heard that the English forces would evacuate Urfa and all of Syria. As always, we did not believe in the rumor and reassured the Armenians, who immediately became very afraid. But on 20 October it was certain that the rumor was true and that the English would leave. Great panic among the Armenians. The Turks also threatened quite publicly and triumphed that they will take back the Armenian women whom they had to release from their harems since the Armistice and later under the pressure of the English. A Turk told an Armenian miller that he would take his mill away from him again, and so on. The fear increased more and more, also the excitement, and we too had the conviction that, even if there might not be any massacres, at any rate the Armenians would again be deprived of all their rights. The English negotiated with the Mutesarif and he promised that nothing would happen, but we have since learned what his word means. – But on 24 October the happy news spread that the English would be replaced by the French. Great joy of the Armenians, anger of the Turks. – On 27 October, Captain Lambert and Lieut. Deloire (…) arrived. On 1 November the last Englishmen left Urfa.

19 February 1920: (…) As time went by, it became more and more obvious that this time the Turks’ hostilities were mainly directed against the French. The Armenians were at least assured of this. After all, the Armenian leaders received several anonymous letters advising them to be on their guard. For example, they were once invited by the Turks to a mosque for a meeting, but were prevented from attending by anonymous letters. (…)

Kurdish riders had been seen in the distance. In the meantime Andreas [Vischer] had arrived from the city, and we learned that the Baderli Kurds had given the French an ultimatum to leave Urfa in 24 hours or they would attack. Now we all hurried to the hospital. At 5 o’clock we were told that the water supply had been cut off, but we were able to fill all the containers before then. Dr. Armenag’s family with 2 children and many Syriacs had fled to the hospital. I immediately asked Dr. Armenag to send some of his supplies as well (…). The approximately 50 or 60 Syriacs also had nothing with them. We could not send them away, of course, but we said that if food and water were scarce, we would have to take care of our employees first and foremost. (…) It remained quiet all Sunday, although the ultimatum had expired by noon. Even in the afternoon they were still taking wood supplies from our house. Of the Syriacs, about 23 were still with us; others had taken refuge in vacant houses nearby. The entire neighborhood outside the city had emptied out in the last few days. (…)

26 February 1920: – From the Syriacs we understood that the government had made inquiries among them and because many men were missing (…), the Turks suspected that the Syriacs had been armed by the French and were fighting on their side. The Syriacs who stayed behind in the city were now threatened and so they decided to pick up their people here. At first, no one wanted to go. But gradually 17 Syriacs, 4 Armenian women, (…) in total 39 people, decided to move to the city. (…) While the people were making themselves ready, I asked the 2 Turkish gendarmes whether they would also help to shoot at our hospital. Their answer was, of course, that it was not the Turks who were shooting, but the Ashiret (tribes). I showed them the many bullet marks on the wall of the house and said it was a shame to shoot at a hospital like that. “It is not us, it is the eşeks (donkeys) who are doing this”. (…) After all, we know very well that the gendarmes are participating above all. The Syriacs told that there were 300 Annesi Arabs in the city, otherwise there was not much enthusiasm. The Turks had great losses. 200 men and the tribes about 70. (…)

Tuesday, 10 May 1920 the cannons were taken away to Surudj [Suruc]; on Sunday and all these days many troops and tribes were seen leaving. Now a battle was expected on Wednesday or Thursday, but nothing happened, not on Thursday, not on Friday. Slowly people believed more and more the rumor that the French had withdrawn from the Surudje plain and had occupied only the railroad. It was also said that they had received orders to withdraw completely from northern Syria. Which is true? We don’t know anything, but on 7 May the French are not four hours from Urfa and it would have been easy for them to take Urfa and then they evaporated. – Thank God, we had to say, because if they had taken Urfa by force first and left afterwards or left Urfa unoccupied as they did in Aintab, it would have been terrible for the Christians. – The Christians are afraid, but thank God since Saturday, 15 May, there are again rumors of an American (!) army approaching. Also, an American, Italian, British commission is said to be on its way to investigate the French massacres in Ferri-Fashä.

On Wednesday, 19 May, one of the two Turkish battalions left – for Mosul or Mardin, or to meet Mahmud Bey, the son of Ibrahim-Pasha, who is holding out against the French? (…)

Rumors! – It is said that the French are back in Surudj [Suruc]. Surudj and that region have been completely plundered by the Turks before, and the Kurds are now on the side of the French. Already a few days ago one heard that the railroad line was being repaired by Kurds, to whom the French pay huge wages. In any case, everything is upside down and if one power does not gain the upper hand, the Kurds, Turks and Arabs and again the individual tribes will devour each other. – There will be a dearth here. The butter time passes and almost no butter has come to the city, in the villages there is butter like water, but it cannot be brought to the city. It is the same with the fresh cheese, which is preserved in spring for the whole year. How will the harvest be? The Armenians are boycotted by the Turks, they do not allow any work to be done by them. Often the Armenians have difficulty in obtaining the necessary food on the market. (…)

Excerpted from: http://www.aga-online.org/texts/erinnerungen_an_urfa.php?locale=de