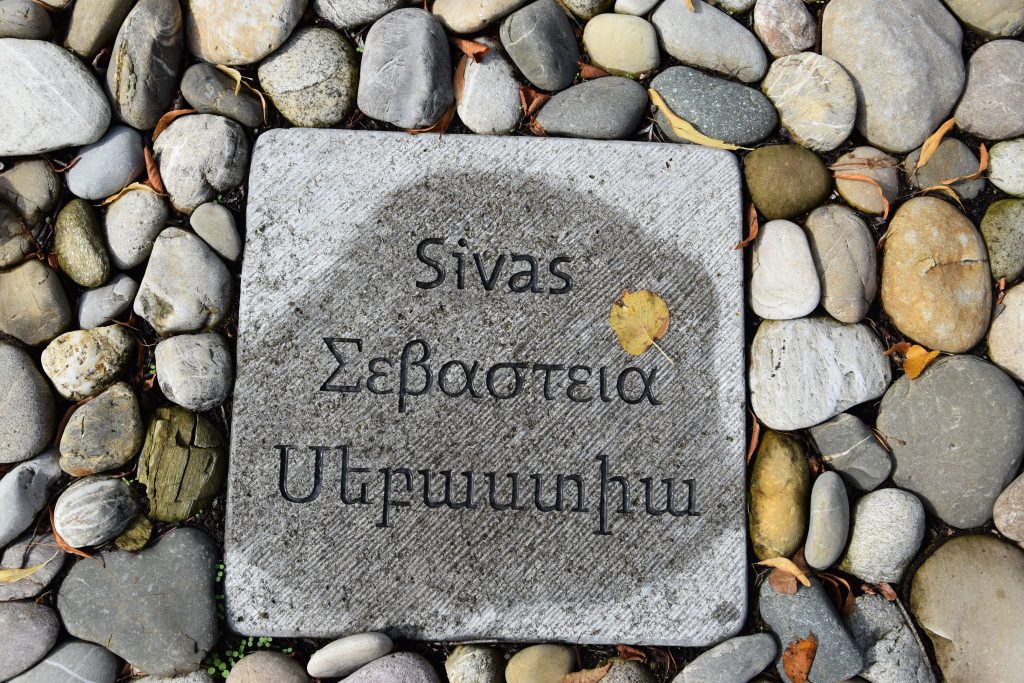

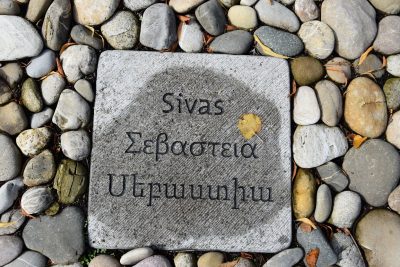

Armenian Population

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 31,185 Armenians in the kaza Sivas, maintaining 13 churches, four monasteries, and 19 schools for 1,980 children.[1] Nearly two thirds , i.e. 20,000 of the Armenian population of this kaza, lived in the regional capital, Sivas city.[2]

Destruction

In early April 1915 the authorities took all the measures required to completely cut off relations and correspondence between Sivas and the neighboring villages: “No one knew what was going on, even in a village just an hour away.”[3]

Sivas City

Population

According to S. Ioannidis, around the middle of the 19th century the population of the city was 17,000 and the majority were Muslim Turks.[4] In 1914, Sivas had about 45,000 inhabitants. Over a third were Armenians, the rest Greeks and Turks. Before the forcible Exchange of Populations (1923), Sivas consisted of 43,000 people of whom 1,500 were Greek and 9,100 were Armenian. After the exchange, in 1927, the population reduced to 29,700.

“In 1925 there were reportedly around 3,000 Armenians left in the vicinity of Sivas. By 1929 this number had fallen to 1,200. A 1939 source gives a figure of around 2000, out of a total population of about 35,000. There were about 300 Armenians still living in Sivas in the 1970s, this had dwindled to under 50 by the late 1990s. There is also still a scattering of Armenians, mostly elderly, in villages around Sivas. Many villages also have one or two inhabitants who will say that they have Armenian mothers or grandmothers (and probably many more who will not publicly admit it).”[5]

The city boasted a large number of churches. The Armenian Apostolic community had six churches (cathedral Surb Astvadsatsin, Surb Sarkis, Surb Minas, Surb Prkich, Surb Hakob, Surb Gevorg, later serving as a Greek Orthodox church), four monasteries (Surb Nshan, Surb Hreshatakapet, Surb Anapat, Derdzak), an orphanage, a hospital and several schools in Sivas until the Ottoman Genocide. In 1915, the Armenian Sanasarian College, which had been moved here from Erzurum in 1912, was closed. The Catholics had one church with the seat of the Metropolitan of Sebastea <(dedicated to St. Blasius, a 4th century saint martyred in Sebastia). The Protestants maintained two churches and eight schools. At least 283 ancient Armenian manuscripts were kept in Surb Nshan.

“Sevasteia has many buildings and monuments including an Armenian Monastery (Holy Cross) [Surb Nshan – Holy Sign] which is believed to have been built by the Apostle Thadaio [Thaddeus], and the Gök Medrese which was built by Kaloyannis of Konya/Iconium (c. 1272). According to S. Ioannidis close to the town there were well known salt works as well as mines. Wheat, legumes and fruit were also in abundance in the region. Before the forcible Exchange (1923), the Greeks had a church (Saint George) which was formerly an Armenian church, as well as a primary school.”(6)

View a list of the Greek settlements of Sivas

History

Founded in the 1st century B.C. as Megalopolis, Sebasteia became the capital of the Roman province of Armenia Minor (Armenian P’ok’r Hayk) under Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305). Later it was part of Pontos and Byzantium. After losing the Battle of Man(t)zikert in 1071, Byzantium lost Sebasteia to the Seljuk Turks. And in 1408 the city was occupied by the Ottoman Turks. Gradually the Hellenistic influence in the city decreased.

A Greek account summarizes the local history as follows:

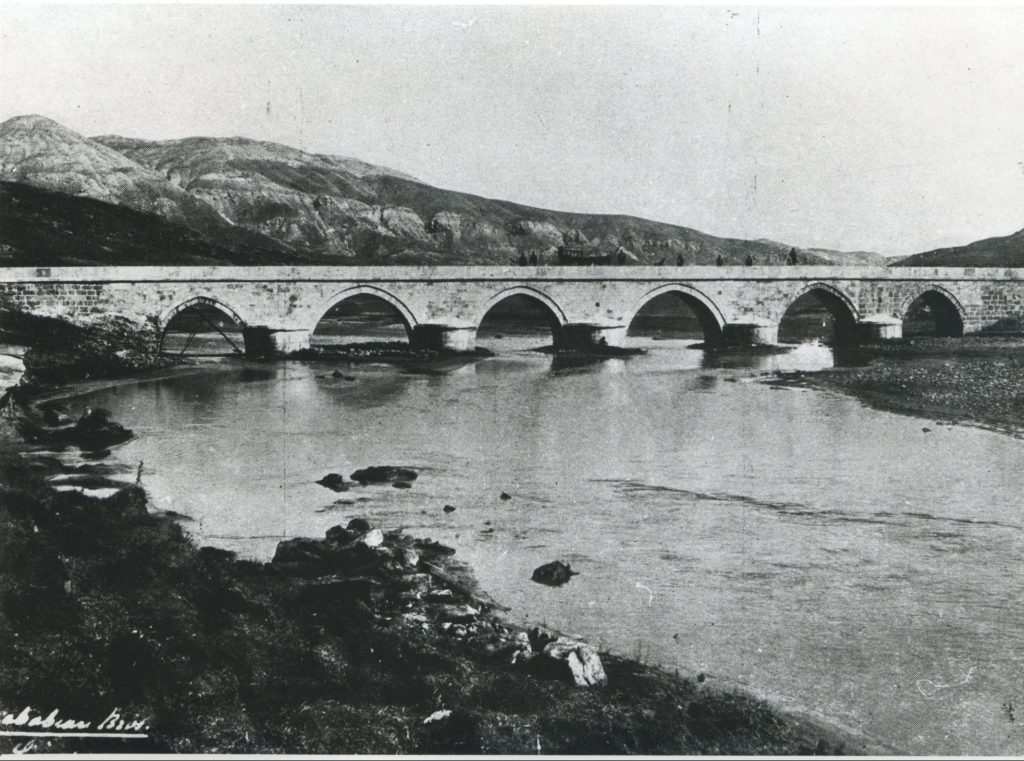

“Sivas, which is known by Greeks as Sevasteia (Gr: Σεβάστεια) was in earlier years referred to as Suvaz and was an ancient Pontic town (…). The town was built at the foot of Mount Paryadris and 2km from the Alis/Halys River (Tr: Kızılırmak – ‘Red River’). (…) Close to the town is a road that links the northern regions of Asia Minor with Kayseri as well as the road that leads to Baghdad. There are three bridges in the region which pass over the Kızılırmak. One was built during the Roman era and leads to Tokat, while the other two are for roads leading to Kayseri and Baghdad.

A number of archaeologists believe ancient Sevasteia is located 8km from today’s town at a village named Gavras (Gr: Γαβράς) which is close to the Kızılırmak. According to many researchers ancient Sevasteia was called Kavyra (Gr: Κάβειρα). Oeconomidis identifies Neocaesarea as being close to Kavyra. Later, Pompey renamed it Diospolis (Gr: Διόσπολη) and Marcus Antonius passed it over to the son of Pharnaces and grandson of Mithradates [Mithridates] VI. Later, it came under the rule of Polemon and following his death his widow Pythodora renamed it Sevasti to honor August which the Greeks referred to as Sevasto.

In close proximity to today’s Sivas was the Lake of Sebaste where the 40 martyrs were killed. S. Ioannidis who visited the region in the mid-19th century mentioned that the lake had all but dried up. Following the Persian Wars, Justinian paid extra attention to the town and built walls around it while during the years of Procopius a large fortress was built in the centre of the town. In the 11th century the Armenian king Synecherin [Seneqerim] swapped the district Baspurakan [Vaspurakan] in his own country, with Sevasteia which thus became the capital of Armenia Minor. The town was later ruled by the Seljuks, Ottoman Sultan Beyazit I (Bayezid I; 1397) and Tamerlane (1400). Tamerlane had ordered his cavalry to trample over 4,000 children of the town following his retreat from the town and subsequent handing back to the Ottomans.” (7)

Destruction

The entire population of Sebastia was subjected to the Hamidian massacres in 1895. In 1913, there was a boycott of Christian entrepreneurs and merchants in the city of Sivas.

Arrests and deportations from and to Sivas 1915-1923

In April/May 1914, the market of Sivas was the victim of a fire. In 1915, the Armenians of Sivas town were not really targeted until May, when the Armenian employees of the Post and Telegraph Office were dismissed. This dismissal was followed “by that of all other Armenian civil servants, such as municipal physicians and pharmacists, gendarmes, and so on. (…) [Governor] Muammer invoked the Armenians’ lack of cooperation to justify launching a vast confiscation campaign that led in turn to the arrests of the city’s notables (one of the first to be imprisoned was the famous arms-maker of Sivas, Mgrdich [Mkrtich] Norhadian. (…) The first round-up was followed by a second wave of arrests, launched on 23 June, that led to the apprehension of around 1,000 men. Thus, a total of 5,000 people were crammed into the city’s central prison and the cellars of [two] medreses [Şifahdiye and Gök].[8]

“As in Harput/Mezre, the Armenians tried to put their most valuable belongings in the safekeeping of the American missionaries, especially Dr. Clark and Mary Graffam, but the police limited their ability to do so by blocking the entrance to the American mission. Funds deposited with the Banque Ottoman were also frozen and then confiscated on Muammer’s orders.”[9]

“Between Monday, 5 July and Sunday, 18 July, Sivas’s 5,850 Armenian families were deported in a total of 14 convoys, at a rate of one convoy daily, with an average of 400 households in each caravan. The operation was carried out neighborhood by neighborhood – even street by street – in an order that suggests the most affluent families were deported first and the most modest quarters dealt with last. However, some 70 artisan households were allowed to remain behind, along with (…) the 80 orphans in the Swiss orphanage (…) and above all the approximately 4,000 recruits from the region assigned for labor battalions. The inhabitants of a village near the city, Tavra – millers who provided the city and the army with its flour – were also temporarily allowed to stay behind as were the peasants from Prkenik [Brgnik].”[10]

“(…) also in Sivas, where the Swiss have their orphanage, the staff of the American missionary institution has been forced to be deported. The inmates of the Swiss orphanage were spared until now, but since their house was confiscated by the government and the stately new building was not yet finished, they had to move to the abandoned properties of the Americans. In Sivas, the notables were also arrested first and eight to ten of them were hanged. The Armenian bishop [Father Sahak / Sahag Odabashian, 1875-1915] suffered a torturous death. For the Protestant inhabitants of the city, among whom were some former inmates of the orphanage, the difficult hour of parting from their homeland came on July 7. The night before, they held a moving communion service in their chapel, reaffirming their faith and their resolve to stand firm and support each other in the hard trials that awaited them.” [11]

In the 1915-1923 genocide, Sivas and its surroundings had the largest number of non-Muslims killed. Surviving Armenians who fled to Armenia founded the Malatia-Sebastia district in Yerevan.

“When the Greeks of Pontos were being persecuted by the Young Turks beginning in 1916, Sivas was the destination for those who were being ‘re-settled’ or in effect being sent on death marches. During the same period, in September of 1919, the Sivas Congress took place. The call for the congress was made by Mustafa Kemal three months earlier. It was at the Sivas Congress that vital decisions were made which determined future policies in the War of Independence. On the 2nd of July 1993, 37 people, mostly Alevi, were massacred in what is now known as the Sivas massacre. The victims, who had been gathered at a cultural festival were massacred when a group of radical Islamists set fire to a hotel where the Alevi group had been gathered.”[12]

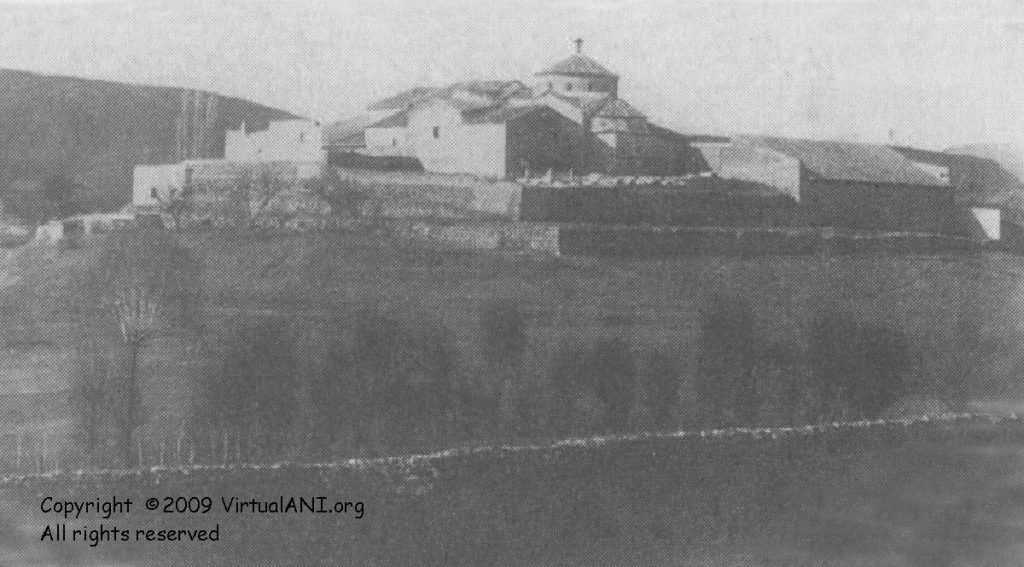

Surb Nshan Monastery: Survived 1915, Demolished in 1978 (?)

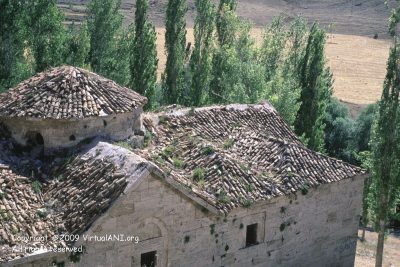

The monastery of Surb Nshan (meaning “Holy Sign” or “Holy Cross”) seems to have been established by Atom-Ashot, the son of King Senekerim, probably while his father was still alive (i. e. before 1027). The monastery was named after the celebrated relic that Senekerim had brought from Varagavank (Vaspurakan), and which was returned there after his death.

The Catholicos of the Armenian Church, Petros I Getadardz, lived in Sivas from 1023 to 1026 before returning to Ani, the then seat of the Armenian Catholicate. In 1046, after the capture of Ani by Byzantine forces in 1045, Catholicos Petros was banished from the city and forced to reside in Erzurum. In 1049 he returned to Ani, where he consecrated his nephew Khachik as Catholicos, but was summoned to Constantinople where he remained in semi-captivity until 1051. Petros was then allowed to live in Sivas but was forbidden by the Byzantine emperor to return to Ani. He took up residence in Surb Nshan monastery, where he built a residency. After his death in 1058 he was buried in a tomb inside the monastery, below the east wall of the Surb Astvatsatsin church.

In 1387/88, Step’anos, the archbishop of Sebastia, was executed for refusing to convert to Islam. For a while the monastery of Surb Nshan was converted into a dervish sanctuary, and other churches in Sivas were demolished.

In 1915 Surb Nshan monastery was the main repository of medieval Armenian manuscripts in the Sebastia region and at least 283 manuscripts are recorded. The library was not destroyed during the Armenian Genocide and most of the manuscripts survived. In 1918 about 100 of them were transferred to the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Others are now in the Matenadaran in Yerevan, or in public or private collections.

In 1939 the traveler H. E. King visited Surb Nshan. He found that the monastery was being used as a military depot and he was unable to go inside. He wrote that the walled enclosure of the monastery was still intact and the main church appeared to be “in an excellent state of preservation“, complete with its dome.

The monastery is now entirely destroyed and a sprawling military base occupies the site. The date of the destruction is uncertain. A short article in The Armenian Reporter of March 30, 1978 says that news had reached Istanbul that the Surb Nshan church in Sivas was being demolished, and that the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul was expected to lodge a complaint. Some books say that the last remnants of the monastery were demolished in the 1980s. A religious shrine (a Muslim one) of some sort still exists within the army base and can be visited for several hours on one day of the week.

Excerpted from: Virtual Ani – http://virtualani.org/surpnishan/index.htm