In the agricultural kaza of Feke where a large number of agricultural crops were produced, forestry and mining were further means of existence.

Armenian Population

According to the census of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople there lived 4,948 Armenians in eight localities of the kaza on the eve of the First World War, maintaining seven churches,

one monastery and nine schools with an enrolment of 661 pupils.[1]

Destruction

“The 5,000 Armenians of the kaza of Feke were deported relatively late, and were even able to benefit from the assistance of Hacın’s American mission. According to [Edith] Cold, the Muslims of Feke and Yerebakan exhibited their hostility to the deportations, with the Turks of Feke behaving in ‘honorable fashion’.”[2]

Town of Feke / Վահկա – Vahka

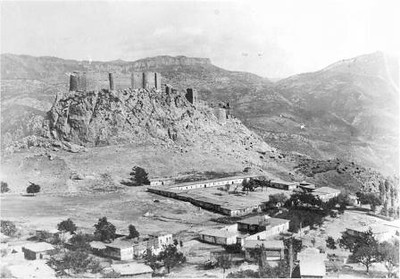

Feke, a small town on an attractive forested mountainside commands a pass across the Taurus mountains directly north of Adana. Eski Feke (‘Old Feke’) was a settlement near the Vahka / Vahga Fortress, 10 km in the northeast.

Toponym

Vahka was the name of the fortified castle built first by Byzantines and rebuilt by the Armenian Rubenid dynasty in the late 11th century.

History

The area was settled by the Hittites in the 16th century B.C., the Persians in the 6th century B.C., conquered by Alexander the Great in 333 BC, and later passed into the hands of the Romans and Byzantines.

Beginning in the 10th century AD the Byzantine government forcibly settled Armenians into Cilicia to act asguards on the frontier with Syria. With the collapse of Byzantine rule in Asia Minor after the Battle of Manzikert it fell upon the Armenians in Cilicia to defend themselves. The Byzantine fortress of Vahka, located 10 km northeast of the town of Feke, was conquered at the end of the 11th century by Constantine I, the Armenian ‘Lord of the Mountains’ (1092–1100), son of Ruben.

In 1137 Vahka was besieged by the Byzantine emperor Johannes Komnenos during the recapture of Cilicia. The fate of the castle was decided by a duel between Constantine, the leader of the Armenian guard, and a Byzantine officer. After the defeat of Constantine, the castle was surrendered, Prince Levon and his sons Toros and Ruben were soon captured (Niketas Choniates, Chronika, chapter 6). They were brought to Constantinople , where Prince Levon died in 1140 and Ruben was murdered in 1141. Toros, however, managed to escape to Cilicia, where he arrived in 1145, recaptured Vahka from the Byzantines and established his own rule. Vahka remained the most important seat of the Armenian dynasty of Rubenids until the coronation of Levon II Rubenian (1150-1219) in Tarsus on 6 January 1199.

In 1275 the Patriarch of Sis fled to the castle during a Mameluk campaign against Cilicia. When exactly it fell to the Mameluks is unknown. It was later captured by the Ottomans.

Below the castle are the imposing remains of a two-story early Byzantine church (Trk.: Kara Kilise) of the 5th/6th century and a late antique/medieval town.

The impressive circuit walls, towers, and vaulted chambers of the castle are positioned at the top of an elongated mountainous outcrop, primarily flanking the more accessible western side. Sheer cliffs precluded the need for defenses at the east. The outer gatehouse, which consists of a winding staircase and an elaborate bent entrance, leads to the summit. Here there are cisterns, residential quarters, and embrasured loopholes for archers. Most of the exterior masonry is the typical Armenian rusticated ashlar with finely drafted margins.