Administration

Administratively, Colonia (Koloneia) was part of the First Armenia province, but after Justinian’s reforms was integrated into the province Armenia Secunda. 1473 it was occupied by the Ottoman Turks and became the center of the Ottoman province of Trabzon, then of the sancak of the Sebastia/Sivas province.

Destruction

In 1895, 5000 people from Şebinkarahisar fell victim to the Hamidian massacres.

Deportations began on 24 June 1915, followed by the complete destruction of the Armenian quarters of the city Şebinkarahisar. Later, only a small number of Armenians re-established themselves in their hometown.

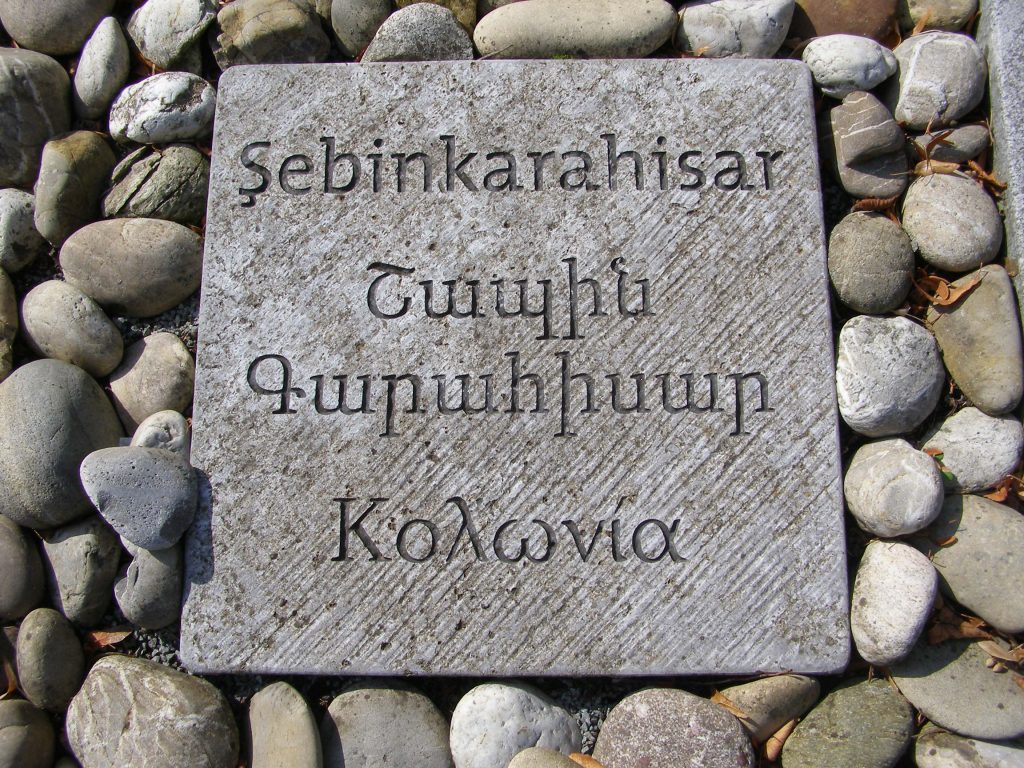

City Şebinkarahisar / Շապին Գարահիսար – Shapin Garahisar / Շաբին Կարահիսար – Shabin-Karahisar

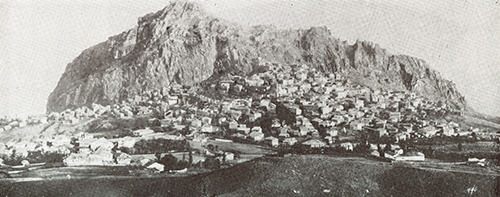

The sancak’s capital city is located on the bank of the Akşehr tributary of the Kelkit (Arm.: Gayl) river, at the foot of a rocky mountain 1482 m above sea level, surrounded by quite fertile lands. There are silver lead mines around the city, which have been exploited since ancient times.

History

Şebinkarahisar was founded in the 60s of the first century B.C. by the Roman general Gnaeus Pompey under the name of Colonia (Grk.: Koloneia). It was a border fortress city between Pontos and Armenia Minor. Along with more than 10 other cities of Lesser Armenia, Colonia was also completely rebuilt by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (527-565). The latter, by renovating and strengthening the Roman fortress, made Koloneia the most powerful fortified city of the Second Armenia province of Lesser Armenia (Armenia Minor). A stone lion with two heads is placed at the entrance of the fortress door. At the western end is the big octagonal tower of the fortress. Remains of a Byzantine chapel were preserved inside the fortress until the beginning of the 20th century.

Population

Under Byzantine rule, Koloneia had 25-30,000 inhabitants, mainly Armenians and Greeks.[1]

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Şebinkarahisar’s Armenian population was about 400 houses. The Greeks and Turks were almost equal. In 1872/1873 there were 502 Armenian, 150 Greek and 2,000 Turkish households in Şebinkarahisar.

According to Raymond Kévorkian, with 4,918 inhabitants Armenians formed the majority population[2] of the city, while other sources give the number of Armenians as high as 7,800.[3] “In 1914, there were also five big Armenian villages in the immediate periphery of Şabinkarahisar, with a total population of 9,104. Four kilometers northwest of the city lay Tamzara (with an Armenian population of 1,518), Buseyid (pop. 510) and Anerği (pop. 646) lay five kilometers southwest. Ziber (pop. 752) and Şirdak (pop. 667) were located to the south.”[4]

The main occupations of Şebinkarahisar’s population were crafts, internal and external trade. The city market had more than 60 shops and kiosks. The majority of the population of the city, mainly Turks, were engaged in agriculture.[5]

The extraction of silver and lead had a special significance for Şebinkarahisar. According to statistics, the lead mine dates back to the 19th century. However, the considerable amount of income was completely taken away because the exploitation of the mine was handed over to an English trading company. Most workers in the mine were Greeks and Armenians.

In the early 19th century, Şebinkarahisar had two Armenian churches, dedicated to the Mother of God (Surb Asatvatsatsin, built in 1274) and to the Holy Savior. In Şebinkarahisar, Armenians lived concentrated “at the foot of the medieval citadel, perched in a rocky outcrop in the upper quarter around the Cathedral of Our Lady. Piled up one beside the next, their houses, with continguous flat roofs, were all interconnected: the roofs of one row of houses served as a street for the next highest row. To the northwest, a new Armenian neighborhood known as Kopeli, had sprung up in the latter half of the nineteenth century.”[6]

Notable Armenians

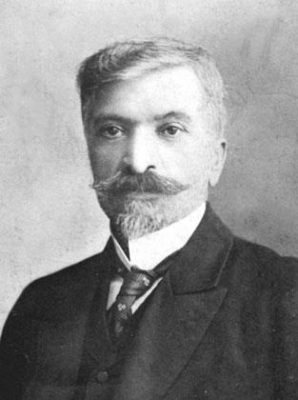

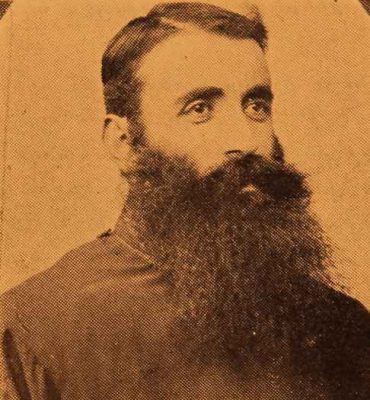

- Harutiun Shahrigian (1860–1915): politician, soldier, lawyer, and author; genocide victim

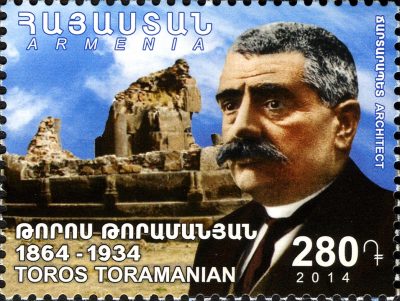

- Toros Toramanian (1864–1934): architect

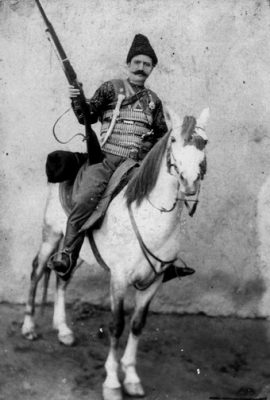

- Andranik Ozanian (1865–1927): general and national hero

- Levon Yesajanian (1890-1935, Athens): poet

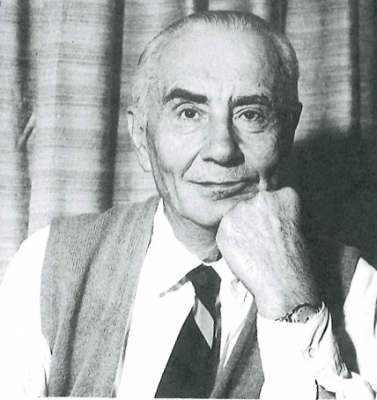

- Aram Haigaz (also Haygaz; 1900–1986): writer; genocide survivor and witness of the failed self-defense of his native city Şebinkarahisar.

The Failed Resistance

The news of the 1 January 1915 murder of the designated primate of Erzincan, Sahag Odabashian (born 25 June 1875 in Sivas), between Suşehir and Refahiye—that is very close to the city—was obviously very alarming for the Armenian leaders of Şebinkarahisar. “The massacre of Armenian soldiers that took place on the road between Erzincan and Sivas in January 1915, after the debacle at Sarıkamiş, followed by the 8 February destruction by a band of çetes [irregulars], under alarming circumstances m of the village of Piurk [also Purk, Burg], located in the neighboring kaza of Suşehir, convinced the Armenians of Şabinkarahisar that preparations were made to massacre them. (…)

The assassination in May of the priest of the nearby village of Anerği, Father Seponia Garinian, the arrest and murder of Nazaret Hiusisian, an emblematic figure in the city and the arrest of well-known personalities (…), compelled the Armenian leaders to take refuge in the quarter around the citadel. (…) The authorities thereupon launched the next phase of operations, which consisted in confiscating weapons and hunting down deserters. That led to extremely violent search-and-seizure-operations.”[7]

During interrogations by the police, the Armenian Apostolic primate of Şebinkarahisar, Father Vaghinag Torigian, was tortured and murdered on 7 June 1915 near Enderes, the seat of the kaza Suşehir, by Kuzurzade Kamil Beg.[8] A week later, soldiers and irregulars started an operation against centers of commerce and craft, located below in the city, arresting 300 men, who were imprisoned in the basement of the konak (government building) and then executed.

On 16 June 1915 the inhabitants of Şebinkarahisar saw, in a distance, the village of Anerği in flames. According to the Armenian eyewitness, genocide survivor and later author of recollections on the resistance in Şebinkarahisar, Aram Haygaz, the inhabitants of the city now spontaneously barricaded themselves in their neighborhoods. People from the villages, attacked by irregulars, took refuge in the city. The Armenians from the city’s lower quarters, known as the ‘Orchards’, began to withdraw to the heights. “The fire that had broken out that same day [17 June 1915] in the lower quarters, where the houses were mainly built of wood, spread, accelerating the concentration of the Armenian population in the upper quarter and, later in the citadel, where (…) between 5,000 to 6,000 people, three quarters of them women and children, found refuge.”(9)

Only 500 of the Armenians were capable of bearing arms, with only 200 weapons in their possession. They were eventually besieged by 6,000 regular forces, starting their offensive on 4 July 1915. “On the morning of the 11th [24 July], the twenty-seventh day of the siege, a white flag was hoisted above the citadel. After hesitating, soldiers and çetes surround the citadel: the handful of males over fifteen were shot on the spot, while some 300 boys between the ages of three and 15 were separated from the others.”[10] The boys were reintegrated into the group of women assembled in the cathedral and the adjacent buildings. Some of the women took poison. “The rest were exiled to the deserts by way of Agn and Fırıncılar.”[11]

Among them was the eyewitness and survivor Aram Haygaz, whose brother, father and other relatives were among those killed. He and his mother were deported. Haygaz survived by converting to Islam, until he escaped to freedom. His memoir of that time, Four Years in the Mountains of Kurdistan, describes his life as a shepherd and a servant, and how he grew to a young man among the Kurdish tribesmen and chieftains.

In the vicinity of Şebinkarahisar, the Ottoman military also incinerated all Christian villages, including ten Greek villages. The population was partly massacred, partly deported.[12]