Toponym

The name Akn (Western Armenian Agn) probably originated from the name of the river Aknaghbyur flowing through the city. The Turkish placename Eğin derives from the Western Armenian version Agn.

Administration

Under Ottoman rule, the kaza belonged to the provinces of Erzurum, Sivas and Mamuret ül-Aziz (Mezre-Harput).

Population

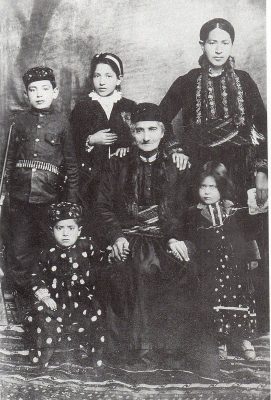

In 1914, the kaza of Akn boasted an Armenian population of 16,741, living in 25 villages and towns and maintaining 25 churches, three monasteries and 20 schools, attended by 1,300 children.[1]

A part of the Armenian population of the kaza where Hayhorom (‘Armenian Romans’; Trk: Hayhoromlar; also hayhurumlar) since the times of Byzantine rule over the region, i.e. they belonged to the Greek Orthodox (‘Rum’) denomination (millet). By the 20th century Hayhoroms in the kaza of Akn were essentially concentrated in five villages (Vag, Zorak, Musaga, Sirzu, Hogus).

Notable Armenians

- Babgen Siuni (Western Armenian: Papken Siuni; birth name: Bedros Parian; 1873-1896), leader of the Ottoman Bank takeover (26 August 1896)

- Misak Metsarents (1868-1908), born in the Binkyan village in the wealthy Metsaturian family; poet

- Siamanto (1878-1915), Armenian writer, poet and national figure arrested on 24 April 1915 and killed during the Ottoman genocide

- Nikol Galanderian (1881-1944), Armenian composer of children’s songs.

Death Vision of a Celebrated Poet

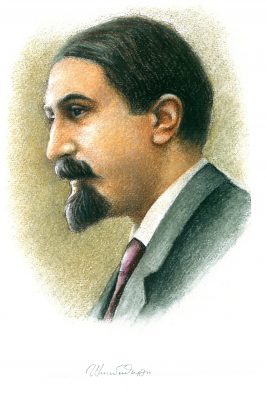

Siamanto (Siamant’o – Սիամանթօ; i.e. Atom Yarjanian or Earčanean; Ատոմ Եարճանեան), is considered, along with Daniel Varujan, the most important Western Armenian poet of his time. He was born Atom Yarjanian in Akn on 15 August 1878 and was murdered during the deportation in August 1915. From the western Armenian province, Siamanto moved to Constantinople in 1891, where he attended high school. Between 1896 and 1908, under the impression of the Armenian massacres, he fled abroad and lived in exile; in 1897, he studied in Cairo, Geneva, London and Paris.

Like many Western Armenian intellectuals, Siamanto came under the influence of Francophone culture during his studies in Paris, especially the French Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine (1844-1896) and the Belgian lyricists and dramatists Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) and Émile Verhaeren (1855-1916), who were committed to French Symbolism. As a member of the national-revolutionary Armenian party Dashnaktsutiun, the latter’s Flemish national pride and exaggerated pathos were as much a part of Siamanto’s nature as Verhaeren’s fight for the cultural independence of his Belgian homeland or Maeterlinck’s sense of the oppressive omnipresence of death, which Siamanto expressed in his first poem Death Vision in 1898. After the Young Turk revolution against the despotism of Sultan Abdülhamit II, Siamanto returned to Constantinople in 1908. There he learned first-hand details of a recent Armenian massacre from letters sent to his family from Adana by his friend, the doctor Tiran Palakian, and under their impression wrote the poetry cycle Red News from My Friend, which his colleague Varujan described as a “gifted song about crime”. Reality had caught up with the poet’s dark fantasies, describing his devastated, depopulated homeland as an inferno reminiscent of Dante: Death, screams from the afterlife, twitching shadows of monsters, cawing ravens, hyenas and wolves lured by the smell of decay, blinding lightning, deafening thunder, and dark nights of terror in an unleashed, raging nature.

Death vision

Slaughter, bloodshed, butchery.

Through our cities, our land

Murderers move with booty and blood

among the dead and dying.

Crow flocks swoop,

their beaks bloody, their laughter drunken.

The fiery wind angrily smothers the dying

and the silent lament of old men

who flee in droves along country-roads.

In the midst of the night, mists of blood

fountains rising from the trees.

In wild panic, herds rush

into blazing fields.

Young and old lying slaughtered in the streets,

Butchered generations, indescribable.

Slowly, tropical heat arises,

from the burning of ancient cities…

Under marble-heavy falling snow

freezes the loneliness of the ruins and the dead.

O hear the dreadful creaks of hearses

Under their full load!

Hear the tearful prayers of mourners,

Whose march stretches from the gorge

To the mass graves!

Listen to the last breath of agony,

beneath gusts of wind that shred the trees:

“Oh, dare not come nearer, come not nearer,

Stay away from the graveyards and the sea!”

On red waters I see ships in a distance,

laden with corpses.

From convulsions of the intestines

Skulls and bones appear to me:

“Hear, hear!”

To the dogs’ horror, dying men howl,

reaching me from plains and graves:

“Slaughter, bloodshed, butchery!”

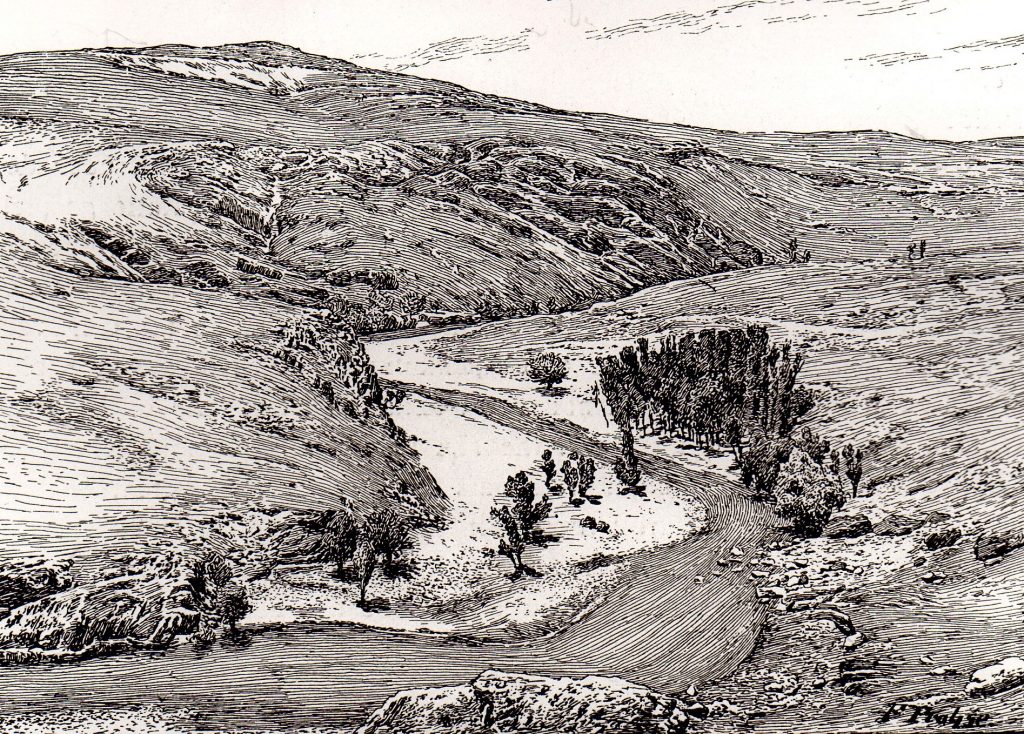

Emigration

“With an economy based on wine-growing and tanning, the mountain district, in which the villages were for the most part located in the highlands dominating the Euphrates, suffered from a shortage of arable land and had for centuries been sending emigrants elsewhere. Thus, many of the Armenians from Agn could be found among the prominent bankers and jewelers of the Ottoman capital, but also among the high-ranking government officials; the last famous example was Gabriel Noradounghian, foreign minister from 1912 to 1913 in the last liberal Ottoman government.”[2]

As a result of the strong immigration of Armenians from the kaza Akn/Eğin to the capital Constantinople, the dialect spoken in Akn developed there in the mid-19th century into the general West Armenian literary language (ashkharhabar).

The Akn Amiras: Providing Service and Moneyed ‘Aristocracy’ for Constantinople and Smyrna

“In the course of the seventeenth century, prior to the use of the amira title, wealthy Ottoman Armenians were given the titles of hoca and celebi. These people similar to their successors held important posts within their communities and the Ottoman circles. They controlled much of the Ottoman financial affairs, and at the same time governed the Armenian millet.

Starting from the eighteenth century, the above-mentioned titles were replaced by amira.[3] (…) it was an ‘honorific [title] which takes wealth, court position and status into account.’ Moreover, the title of amira was used exclusively for the affluent Armenian Orthodox men, and not to the Armenian Catholics, who were referred as celebis. Hence, not all people had the chance of joining the ranks of the amira class. The majority of amiras originally came from the Ottoman city of Agn (Eğin in Turkish). But there were others who had moved to the Ottoman capital from the cities of Van, Sivas, Kayseri, and Divrigi.”[4]

The Armenian communities of the kaza and town Akn have given many prominent writers, doctors, teachers, artists, lawyers, national and religious figures. For about 200 years, from the 18th to the early 20th century, Akn also provided prominent amira families; in Constantinople and Smyrna these were the Datians (Western Armenian: Dadian), the Jezairlian and others.

“The Dadians administered two gunpowder factories. Dad Arakel, one of the main pillars of the Dadian family, established a gunpowder factory in 1795. He was also appointed as the chief gunpowder producer in the Azadli factory. Later on, his legacy was kept alive by his descendants Hovhannes and Boghos Dadians, who founded an iron and steel factory in Zeytinburnu in 1844. Westerners called this establishment as the ‘Grande Fabrique’ since, it provided the required commodities such as ‘pumps, small machines, steam engines, swords….’ to the Ottoman military.

In his turn, Hovhannes Amira Dadian was one of the favorites of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II. He got famous after having created a new machine that received the Sultan’s deep appreciation. On several occasions, Hovhannes Amira travelled on his behalf to Europe, to introduce new methods of production to the Ottoman factories, which suffered from lack of modern European machines. This amira founded a technical school to prepare well-skilled staff for the above-mentioned iron and steel factories. Moreover, during his stay in Europe, he also learned new weaving and gun-making techniques, which he introduced to the Empire. In 1836, a wool clothing factory was established in the Ottoman city of Sliven (currently in Bulgaria) by Hovhannes Dadian. Similarly, he along with Boghos Dadian built a broadcloth factory in Izmit in 1842. Another similar foundry existed in Hereke, established in 1843 by these two men. However, it was later converted to a silk factory having machines imported from Austria. Taking these events into consideration, one clearly understands the important role played by the Armenian amiras of different professions in guiding the Empire towards progress.”[5]

Destruction

November 1895 – September 1896

British archaeologist David George Hogarth noted massacres of Armenians in Akn on 8 November 1895 and throughout the summer of 1896.

On 3-4 September 1896, Muslim bands attacked Akn town, and Kurds attacked the surrounding Armenian villages (Lichk, Binkyan, Zmara, Kasma, Apuchek, Kamarakap, etc.), massacred the inhabitants, looted and set fire to the houses. According to an eyewitness, the number of victims reached 3,000. In the next two decades, the Armenians rebuilt the city, and life in Akn became more active.

1915

“The first arrests in the kaza were made on 22 April 1915, for no apparent reason. The same day, the town crier announced that arms had to be surrendered to the authorities. This order was followed by systematic house searches and new arrests. (…) 248 people were arrested in the course of 24 hours in Agn alone. Similar events occurred in the kaza’s villages around the same time.”[6]

On 1 June 1915, the auxiliary prelate, Father Petros Garian (Bedros Karian), and another 30 of the town’s leading citizens, “including the kaza’s tax collector, Srabion Papazian, a member of the district’s council, Margos Narlian, the head of the Armenian orphanage, Mardiros Semerjian, and also B. and H. Diradurian, Gh. Vartabedian, B. Khanarian, K. Ardsruni,Avedis Palushian, Avedis Gananian, and Dr. Sahag Cholakian. Those arrested were sent off to Keban Maden with 90 other men, loaded on a raft, and drowned on the Euphrates.”[7]

By an extended draft of 7 June all, concerning all males between 16 and 18 and 46 to 60, 400 men were ‘mobilized’ and then under guard taken to three places on the banks of the Euphrates, where they were tied together in groups of five and thrown into the river. Since there had already been a general conscription for males between 18 and 45 years of age in the previous year no Armenian men were left in Akn except those older than 60 years.

The general deportation started in late June. “The authorities announced, however, that they were willing to allow those families who agreed to convert to Islam to remain in their homes. About 5 per cent of the population succeeded in avoiding deportation in this way.

Three convoys were deported. The first included the population of the villages, the second was made up of people from the outskirts of Agn and one of the town’s neighborhoods, and the third and last, dispatched on 5 July (…) comprised the rest of Agn’s Armenian population – that is, around 7,000 people.”[8]

The march was deliberately made long and arduous so that as many deportees as possible would perish. While a caravan leaving Akn could by the direct route reach the Kırk Göz-Bridge over the Tohma river in four to five days, the first deportation convoy from Akn reached it only after a 24-day trek. A surviving deportee of this trek noted that “12-year-old Turkish and Kurdish boys came to the [transit] camp to help themselves to girls. (…) According to the Constantinople Armenian Patriarchate’s sources, some 400 Armenian children were being held in Turkish homes in Agn in late 1918. There were an additional 900 Armenian survivors, half of them from the villages of the kaza.”[9]

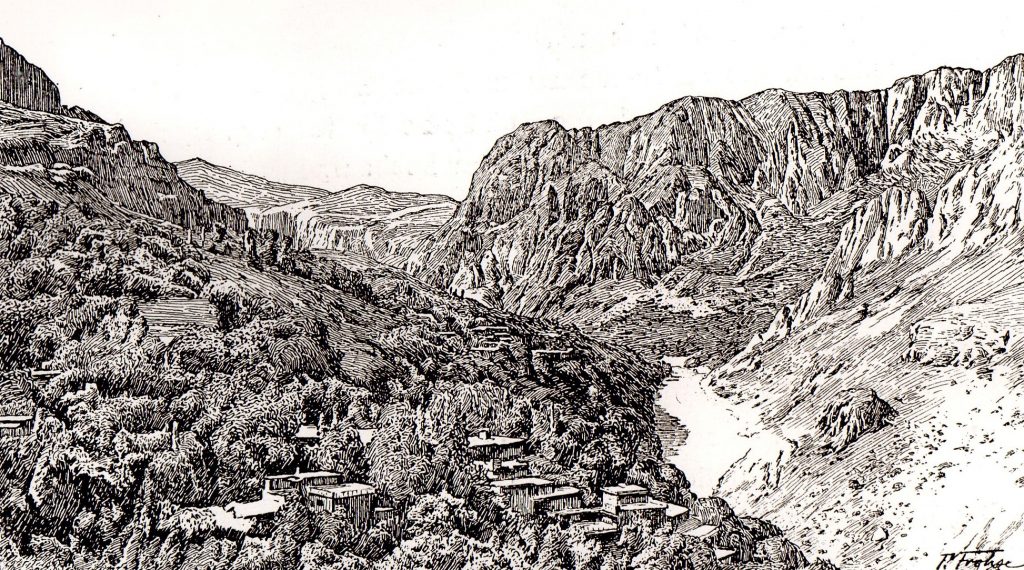

Akn Town

Akn is located on the right bank of the Western Euphrates (Karasu River), in a tree-lined valley between the Tauros and Anti-Tauros mountain ranges, more than 1000 m high. By 1911, British archaeologist David George Hogarth, writing for the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, described Akn as an important town in the Mamuret ül-Aziz Vilayet: “…picturesquely situated in a theatre of lofty, abrupt rocks, on the right bank of the western Euphrates, which is crossed by a wooden bridge. The stone houses stand in terraced gardens and orchards, and the streets are mere rock ladders.”[10]

Akn was famous for its architectural monuments, monasteries, churches, bridges, and the antiquities of the area. In the 11th century, the Artsrunis built the Narek Monastery (Narekavank; named after the monastery of the same name in Rshtunik), and later, Surb Nshan Monastery (named after St. Nshan Monastery in Varag). At the end of the 19th century, Akn had two functioning Armenian churches: Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God) and Surb Gevorg.

Population

At the beginning of the 19th century, the city had about 10,000 inhabitants, of which about 5,500 were Armenian Apostolic Christians. They maintained two churches and two schools. According to the data of 1880, there lived 5,442 Armenian-Apostolic Christians and 4,286 Muslims (Turks and Kurds) and Hayhorom in Akn.

According to the Turkish state census of 1929, only 41 Armenians remained in Akn.

The pre-WW1 population was mainly engaged in handicrafts (tailoring, weaving, shoemaking, blacksmithing, ironwork, textiles, etc.) and trade. At the end of the 19th century, there were up to 300 shops, kiosks, workshops and taverns in Akn.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were two Armenian schools for girls and boys in Akn (Narekyan and Nersisyan), as well as four private schools for had 360 students.

Akn has played a significant role in Armenian culture. Not only had the population developed its own dialect, but Akn was also famous for its folk songs, pandukht[11] songs, poems. From 1870 the newspapers Flower, Euphrates, and Whip were released in Akn. In 1873 the theatre play ‘St. Nerses the Great’ was presented here.

History

In ancient times, Akn and its vicinities was part of the Second Hayk province of Armenia Minor.

According to legend, after the destruction of the capital city the Bagratid kingdom of Shirak, Ani, a part of its inhabitants came here, meeting a cold spring (the Water of Immortality Fountain), and founded a new city, calling it Akn.

In fact, Akn was founded around 1021 by King Senekerim-Hovhannes Artsruni of Vaspurakan who was urged by Byzantine to move his residence to Sebastia (Sivas) in 1022; he called the new town Marantunik. Thousands of Armenian colonists from the lake Van region settled there. Thousands more Armenian refugees from Ani fleeing from the devastating earthquake of 1319 also settled in the region. Under Byzantine rule, a portion of the Armenian population converted to the Chalcedonian creed and joined the Byzantine church, becoming known as Hayhorom (Trk.: Hayhurum; ‘Armenian Romans’).

At the beginning of the 16th century, Akn fell under Ottoman rule.

The 1923 forcible population exchange between Greece and Turkey (Greek: Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, Turkish: Mübâdele) compelled the Hayhorom, or Armenian-speaking Greek Orthodox minority population to leave their homeland. After a most difficult journey of eight months and more than a thousand kilometers, they reached the shores of the Aegean and were transported (after various stations) in Diavata, near Thessaloniki, and Kastaniotissa (new Eğin), at the Greek island of Evia.