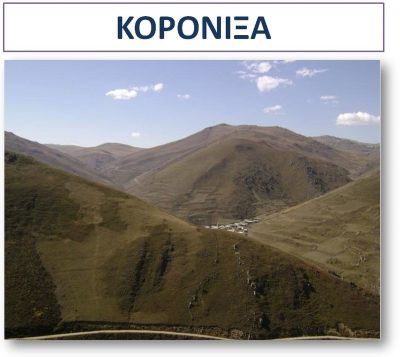

The Index Anatolicus notes that the town of Korónixa (Gr: Κορόνιξα) was named Koróxena (Κορόξενα) until 1895. Until the forced Greek-Turkish population exchange, the large municipality consisted of nine quarters. In 1928 the name was changed to Görükse.

In the 1840s, part of the Greek Orthodox population emigrated to Bolaman, Fatsa and Habsamana, from where they continued their migration to Adapazarı.(1)

Emigration from Chaldia

Situated near to the metallurgic center of Gümüşhane (Gr: Argyroupolis), the population of Koronixa took part in the Greek emigration from this area, which in the 19th century had become a specific of the demographic trends in the Chaldia Metropolitan, to which Koronixa and her emigrants ecclestically belonged.

“(…) The issue of migrations from the Chaldean region has been of concern to Pontian Hellenism for a long time, as the strong escaping of the inhabitants saw the danger of its complete disintegration. However, there was no possibility of stopping this large outflow of Chaldean residents to the Caucasus, western Pontus and the metropolitan areas of Asia Minor. However, the cohesive fabric of the metallurgical immigrants with their place of origin was the fact that they all belonged ecclesiastically to the Chaldean Metropolitan, whose Metropolitan appointed a commissioner to handle on his behalf the ecclesiastical things of the area.

The areas of the new facility were in different directions. A part of the inhabitants of the numerous villages of Chaldea, in 1828, following the outgoing Russian army, settled in the Chalka region, near Tbilisi, where it formed a group of 43 Greek villages. Others settled in various other parts of the Caucasus at the same time or during the Crimean War (1856). Total number of immigrants to the Caucasus: 348,0009. Another section of immigrants moved southwest and settled in the area of Ak Dag Maden, in the province of Ankara, between Ankara and Sebastia, where it established 30 Greek villages.

Other establishments were Kioumé Maden in the western Pontos, Denek Maden in Ikoni, Bereketli Maden and Bougu Maden Taurus.

Not to forget the descent of a significant number of immigrants down the Chaldean River to the littoral areas of Tripoli [Tirebolu] and the littoral as well as the western Mediterranean Sea.

The inhabitants mentioned by the author come from metallurgists in the town of Koronixa or Koroxena, Chaldea, near Argyroupolis.(…)”

Source: Excerpted from an article by A. Pavlidis, “GUMUSHANE & KORONIXA (ARPALI KOYU) -ΑΡΓΥΡΟΥΠΟΛΗ ΧΑΛΔΙΑΣ & ΚΟΡΟΝΙΞΑ ή ΚΟΡΟΞΕΝΑ”, https://adapazari-pontians.blogspot.com/p/koronixa-arpali-koyu.html

Anastasia Kasapidou: Patrida – The Lasting Pain of the Lost Homeland

You’ve come, Pulopom, my chick!

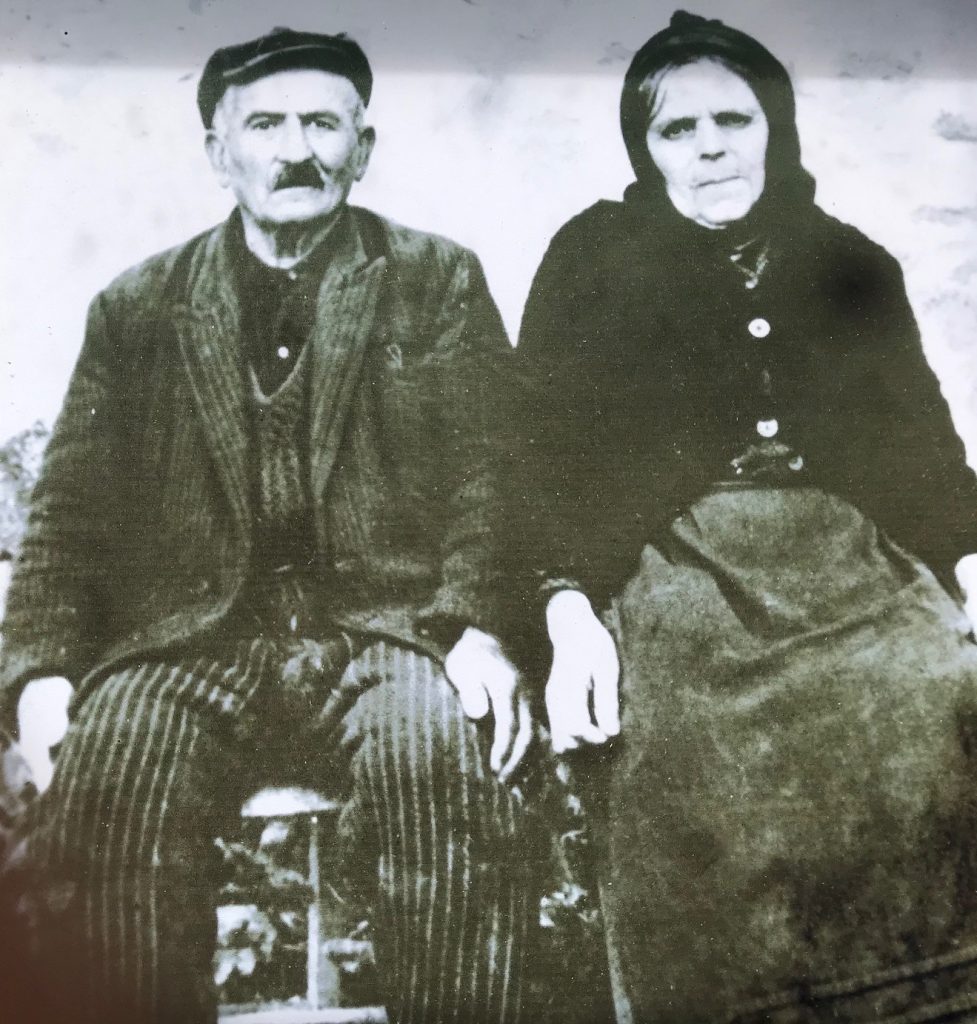

As if someone had nailed her there, I find my grandmother Despina Kastanidou – we called her Yaya (grandmother) – always in the same position. Sitting in a low squat, picking lentils, chickpeas and beans.

“You have come, my chick, come help me, you see better, my eyes are not so good anymore.”

I sit down next to her on a free stool. Her son Vasos, my uncle, a talented carpenter, had made many such stools so that we could all sit together at the table at Grandmother’s for dinner. We did not have such luxury at our parents’ house. But our mother, gifted like her brothers, had sewn cushions and filled them with straw, and all of us, parents, brothers and sisters, even the smallest, sat on these straw cushions around the low table. We were very happy! This is how we lived then … in Platania.

In my mind I am often still there. Something leads me again and again from the present back to the times when I was with my Yaya. This awakes in me great pain, but also great joy, and I then say to myself: ‘Yes, I am with her again, with Yaya, she talks to me, I listen to her.’ – In such moments of joy, I sit next to her again on the stool in the shade of the mulberry tree and we read out lentils, just like in those days. I want to dwell on this happy memory.

But this silent harmony is often interrupted by Yaya’s painful monologues: “Pitiful homeland, villages full of darkness, pain of all the unhappy people who stayed there. My unhappy, deserted house! My spirit is near you every day. Ah, if only I could be with you, if I could see you all again before I die!”

“What’s wrong with you, Yaya?” I asked her.

“You don’t know, my polupom! I will die with my eyes open.”

“You don’t know, my little girl! Even the moon shone brighter at home.”

“Ah, wretched me, with eyes wide open I shall die.”

To this lament she writhed in pain as if she wanted to represent what she had lost. This lawsuit has paralyzed and hollowed me out. At the same time, I pondered how to die while keeping my eyes open? But I immediately repressed this thought again. No, Yaya is so young, she won’t die! I then trusted her explanation: “You know, my chick, when I die, I will look towards home, I must look for my homeland!”

To my naive question, “Why, Yaya?” she always scanned the horizon of Platania with her gaze. This searching gaze is engraved in my memory and still haunts me today.

In her eyes I recognized the tremendous crime that happened to my little big Yaya. But how she dealt with her misery, how she told it, had dignity and reflected her bravery and kindness. Her narration came straight from her soul. I saw through her eyes what she had seen. Her story slowly seeped into my child’s soul and frightened me. I felt as if she was saying to me:

“You will never forget this, my child. You will pass on this injustice to the younger generations. You must not forget it either.”

This thought of Yaya was a deep sigh from a wounded soul: “Blessed is he who is buried in the ground where he was born!”

Fairytalelike narration and a valuable agreement

I flee from my duties and the gaze of my mother and feel liberated, because I now go to Yaya’s house, which is not far from ours. I usually go to her around noon, forget myself in her stories and only go home at dusk.

To get to Yaya, I have to pass other houses, the teacher’s house for example, a two-storey building where I always imagined that the beautiful Genoveva would drop her long braids from one of the windows at any moment so that her beloved could climb up it. Near Yaya’s house were also the houses of Uncle Foster and Aunt Kelin, which were literally glued together as if they wanted to support each other. With their long, awe-inspiring corridors and mysterious rooms, they were reminiscent of palaces from Thousand and One Nights.

One more short walk, and then I’ll be with Yaya. We’re alone. It’s autumn, and we’re sitting in the kitchen in this intimate atmosphere that I love so much. Here I feel joy and security. The room is filled with Yaya. And again, I hear stories that fill me with sadness and a strange agony. I finally want to know how Yaya’s fairy tale-like narration continues and feel that she wants to confide her grief to me again and ask me to help her to ease the pain.

“How can people be expelled and uprooted from their homeland, their residence, and where do they go then? What would happen if I had to leave Platania?” At such thoughts I panicked, and Yaya’s stories whirled through my mind.

I want to understand exactly what she told me and what I felt and always remember her. I don’t want to forget anything. Without protocol, without witnesses, we had made a “holy” agreement, which I stick to consistently and disciplined – and this with my rather unruly temperament.

My grandmother would tell her story with her jewel-soul – keimilio – and I would listen, it would be a long narration with many episodes.

With each story she would entrust me with a little more of her life. She knew how to tell me a big story in simple words. I felt how she was constantly trying to understand injustices that could not be repeated.

Through Grandmother I carry a principle of life within me. I have to collect what is left of the history of her homeland and her own history. From her I learned to love. Grandmother, who suffered unspeakably when she lost her homeland and her children, was a remarkable person, because she never lost her love and her humanity. Therefore, I must not forget this injustice and her stories.

I also owe her thanks for having taught me the Pontic language from childhood – even against my mother’s will. For Pontic Greek was frowned upon in our new homeland of Greece and was ridiculed.

Yaya taught me great things. I hung on her lips, and I let her tell it now:

“There were many beautiful girls in the quarters of Koronixa, and every man wanted to marry into them. But I come from the quarters of Konstanton, my girl,” Yaya said with a smile. “There were wells with very good drinking water. The cow butter was washed in these wells, and then it smelled of incense. Often in my dreams I am in Koronixa – the sweet splash of the well water wakes me up and brings me back to Platania. In winter, we’d gather pine cones and make fires.”

“You have no idea, my Pulopom, how beautiful it was in my homeland!” And always Yaya added: “We have lived peacefully with our Turkish neighbors. We even went on pilgrimage with them to our holy rock monastery Panaghia Sumela, lit the candle in the church and drank holy water together”.

“My Panaghia (Mother of God), watch over the whole world, and please watch over us too,” Yaya prayed often. “My parents, my father, my mother, my brothers and my children are buried there. Who will light candles for them, which priest will read the prayer for them? Their graves are probably already overgrown with grass. If my eyes had wings, I would fly to see the deserted places and grass-covered graves.” – “O my children,” she lamented, “I always see the face of my eight-month-old son who died on the run when the Turkish irregulars, the Chetes[2], were chasing us. He died unchristened, with no name and no grave. We dug a pit at the edge of a field and covered the child with earth like a field crop so that he would not be devoured by animals. Oh, I have lost everything!”

And so, her lamentation always used to end: “Oh, my Pulopom – when I am in the dead, my eyes will remain open and look for my homeland! Oh, if only my eyes had wings!”

So that’s why she was so keen to look for her home, to see the lost again, I thought, full of bitterness. “My poor Yaya, what are you telling me? What can I do? How can I share your pain?”

Yaya’s facial expression, despite her suffering, had a kindness and sweetness that commanded me to understand her and vow never to forget her stories. That was our secret society. Her sad stories, her lament, strengthened my love for my origins and roots and built a bridge between Platania and the Pontos. In my imagination I drew a wonderful picture of my grandmother’s home, as she described it to me. So, the Pontos became also my home.

But where and how was everything lost? The home, the parents, the children, the well and the monastery of Panaghia Sumela? The words ‘lost, lost’ were always accompanied by deep sighs. “Lost, lost”, it still hums in my ears. I felt that Yaya’s lost home was so far away, she would never see it again. How much I wanted to see this moon, brighter than that of Platania! Sad stories, tightly wrapped like balls of wool, wanting to be untangled.

Yaya abruptly interrupted my thoughts.

“But suddenly our Turkish compatriots have become very angry, my child! I still don’t understand why. We had to leave our homeland. They always looked for trouble and found reasons to provoke us. Once they floated their animals into our cornfield. Your grandfather was outraged and asked why they did that? Then they pointed at us and called us unbelievers who had no right to tell them what to do, and they threatened him with beatings. Among them was the short-legged Mehmet, a Turkish neighbour who filled his stomach every day at our house. Grandfather confronted him, but Mehmet was also excited: ‘You are infidels!’ Panaghia, Panaghia, I did not recognize our neighbor anymore, why did he suddenly hate us, too?

The Turks threatened your grandfather with Topal Osman, who raged in the Pontos with his looters and Chetes. Grandfather was no longer safe. He left the village with his brothers Kostis and Pavlos and hid in the village of Anasto, a resolute woman who remained also my closest friend from home in Platania. Anasto hid all three men for a few weeks in the forest and supplied them with food. She even managed to smuggle them to Trapezunta[3]. From there grandfather went to Batumi, where he worked in a bakery for many years. That’s why he could bake so well.”

I could never get enough of her memories: “Please, Yaya, tell me the story of Aunt Kelin and the one of the Padishahs (Kings) …! – “Aunt Kelin was a beautiful Plataniotissa, an aristocrat, with a figure as beautiful as a cypress and big green eyes. Her first husband died in Pontos. Like many other men, he died in forced labor[4] on the Turkish roads. Aunt Kelin’s second husband was Armenian.”

Although poverty-stricken, Greece has taken in and provided for 90,000 Armenians and around ten thousand Syriacs (Arameans, Assyrians, Chaldeans) in addition to its own displaced persons after the so-called population exchange.

Yaya told a lot, but nothing about her childhood. Maybe she did not have one, I thought sadly. I was firmly convinced that you can only have a childhood in Platania and nowhere else. Yaya’s life seemed like a stopped clock. The memories of her lost home had darkened her life in Platania.

I should not forget

Uncle Vasos is dead!

He was killed by lightning when he was just 27. What an infestation for Yaya! Her son’s death slowed the train of her memory. Like the lightning that had burned her son, her past now seemed sealed. She no longer spoke of her lost home or those left behind. Vasos’ unexpected death did not allow any more questions.

And so, I silently waited for a continuation of the stories. I wanted to know how it would end. Why had they been driven out, why did so many people have to die? And above all: why were they not allowed to stay and not even to visit the place where they had been born? I was afraid I would not be able to understand this story. And how could I keep my promise if grandmother died and her story remained incomplete?

I was paralyzed and could not continue.

“Oh my God, Yaya has lost something again, this time my beloved uncle,” my thoughts circulated. But Yaya admonished me: “Do not forget what I tell you, my chick! You must always keep a clear head! Our dead people are countless, and now there’s one more.” She stared at me with blurry eyes.

“Yes,” I promised muttering, “I’ll never forget her. I will keep the promise and try to remember everything I have remembered.”

Today I sit on the balcony of my apartment and write everything down. I go back to Platania and visit my yaya in my thoughts. I look at the lush garden and the cherry trees in my courtyard in Munich, which reminds me of Platania. Then in my imagination I see Yaya walking through the garden and visiting me! “Yaya”, I then say, “you have entrusted me with a tragic legacy and at the same time you have given me a legacy and a mission. Yes, I haven’t forgotten, I’m writing it all down.” Yaya’s face then glows, she looks at me, strokes me like before and – disappears again.

My grandmother’s voice, the moments with her have engraved themselves in my memory, they don’t give rest and demand attention. Now I am Yaya’s voice and I have to do my part to ensure that something like this does never happen again.

When we lived in the homeland, when we were driven from the homeland

With the bilateral Greek-Turkish Treaty and subsequent forced population exchange, caused by the Lausanne Agreement of 1923, the Christian Pontos Greeks, if they had survived previous massacres and deportations at all, finally lost their homeland. Grandmother’s home was the small village of Koronixa[5] in the Pontos area. When the expellees from Pontos arrived in Platania in 1923, they first lived with Muslims for about eight months.

During this ‘population exchange’ the Greeks of Pontos were forcibly uprooted. There were countless casualties. The Greeks were only allowed to take as many belongings as they could carry on their backs. Turks who had to leave Greece were no less insecure, but they were less afraid and were able to carry their possessions by cart.

Not enough that one had to flee, religion contributed to the enmity as well. For example, the Christian evacuees and current inhabitants of Platania thoroughly cleaned their houses, and the priest said a prayer in each house and sprinkled holy water on it after the Muslims had left. The most beautiful house stands in the middle of the village. Turks had built it in 1923, but could only live there for half a year. It is an illustrious building, a living part of Platania’s history.

The heart of the village is the ancient plane tree, the Platanos, which unifies us and is always waiting for us. The plane tree and this house are eyewitnesses of the local history, and if they could speak, they would not only tell the story of Platania, but also tell us about the senseless conflicts and wars in the world. The plane tree would have convinced us with the serenity of nature and the homeland that, having shared the same soil and the same roots, the roots of love, the whole world is connected.

The Plataniotes had a life divided into two parts and accordingly had two narrations to tell: The story they brought with them from the Pontos, and the story since they settled in Platania. Between the two stories, like a wall, stands the ‘population exchange’. A story before and after, with two burdens: one from the past and the other into an unknown future, for which they needed strength to cope with their own lives and those of their children. All those who had survived the genocide started from scratch here. Many stories of the Plataniotes began like this: “When the exchange took place … After the exchange… Before the exchange…”

Exchange, an end and a beginning… The tragic meaning of this word only came to me much later, although it was closely linked to the stories of my grandmother, and we both shared her memories. But grandmother’s stories began like this: “When we were at home, when we were driven from home, at home we…”

Home, exchange, Venizelos, three words! The mark of the expelled of Platania.

“Venizelos even signed the exchange” …

“Be good to Venizelos” said Pavlos, son of Anasto. “Fortunately, he brought us here, otherwise we would have been dead long ago, the road construction in Turkey would have finished us off and those who didn’t flee would surely have been killed by the Turks.”

But despite all their trials, they did not know whether the exchange was really their salvation or just a farce to convince them to leave behind their homeland, family members and property.

Many Plataniotes believed that the Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos had saved them. But many could not bear the exchange. A persistent pain that killed some within a few years, tortured others for life. Someone like my grandmother would be haunted by it to old age, even to death. In some people, an event caused their hidden wounds to reopen. Time has not healed my father’s pain. I understood that in addition to the suffering he shared with the others, he was tormented by many other mental pains which he endured in silence. Sometimes it seemed as if he had been seized by a mania that caused bitterness.

In 1973 an event reopened his old wounds. In August our neighbour Georgios returned from his trip to his home, to Buca Maden, and reported that he had seen our house. “Our house built with stones stands, indeed it stands and waits for us. Georgios ate figs from the fig tree and the plum tree is still standing,” said Father. I listened to his tense. As he spoke, his eyes lit up briefly, a spark of hope became visible. But after a short while his eyes slowly lost their brightness. I noticed a darkness in them that seemed to turn to anger. Then tears filled his face, running down the wrinkle lines. I wiped his wet face, hugged him tightly, very tightly, just like when I was little. In my arms my father’s pain became a song, a Turkish song, the doctor’s song: “Where is this doctor who heals wounds? He should heal the wound that is deep in my soul…”

It is characteristic of us Pontos Greeks to sing of our joy and also our sorrow. I have often heard the ‘Doctor’s Song’, it was always accompanied by tears. Today I find myself singing this sad song when I am in pain or thinking about where my roots are.

I can’t forget my father’s embrace. I wanted to help him, comfort him.

When I was still an infant, I thought fathers and men in general never cried. Even though fifty years had passed since the expulsion, Father had not forgotten the home he left behind at the age of 14. The bitterness about the lost homeland, the lost home, the lost possessions, the abandoned attendance of Anatolia College was deep. Everything that he had hermetically hidden in his soul, that had petrified his face, now came out with the lament.

Parakathi – nightly gatherings

Our daily routine in Platania was filled with the narrations we heard during the nightly meetings, the parakathi. On cold nights, we gathered with relatives and neighbours around the coal basin and in summer in the gardens. Each had its place, comparable to the Homeric gatherings. Usually I sat next to or opposite our ‘storyteller’. I wanted to listen carefully and also study facial expressions. In this way I learned the history of the Pontos from those who had experienced it, like my grandmother, and could understand their feelings.

They told how they had lived in peace with each other and with the Turks and how this idyll ended abruptly. They talked about the forced labor battalions and their suffering, about their escape and how everyone tried to find a way to escape. They talked about the Great War, which in retrospect was called the World War, about the political machinations and the civil war, which once again divided, decimated and separated the people. They also talked about the dictatorship that robbed them of their freedom of speech, and about exile that silenced them.

At these meetings people revealed themselves, opened their hearts. Before my eyes, many a narrator was transformed and became a person in distress, a revolutionary who wants to change the world and bring peace and prosperity, a person who claims his right. I have listened carefully and tried to find answers and solutions, to make plans and learn more.

Like in an ancient theater performance, the parakathi assembled us in the choros, in the choir. This choir mourned the catastrophes that marked their lives. Those who spoke felt the need to tell the next generation their suffering in a powerful way, in order to leave a legacy for future generations. Yes, we have inherited a pain and a mission not to forget the injustice that has happened. In the parakathi, the stories that my grandmother Peni (as Yaya was called) told were confirmed by the other narrators. They confirmed and kept alive the promise I had given my grandmother.

Merciless River

For me, Anastos’ son Pavlos was the wise man of the village. We perceived him, or at least I always perceived him with a stern look, as if he was constantly reflecting, as if something was bothering him that he was trying to solve. He reminded me of the look my mother gave me. My mother and Pavlos not only had the same stern look, but also the same mania of constantly having to do something and work.

But unlike my mother, Uncle Pavlos opened his heart to the parakathi. There the media had turned off all the stories from and about the Homeland. I knew that he went to school in Abric, his home town, for three years. When he came to Platania fatherless, like me and many others, he had a brother Peter and his mother Anastos.

When he sat on the wide bed in his own house during the parakathi and rested on padded, spectacular pillows filled with the wool of his own sheep, he always delighted us with his stories. The light that fell on the oil lamp threw changing shadows on the walls of the room and let at least my imagination flow. I tried to imagine living beings in these shadows. If it wasn’t too cold, the hot coals helped to keep us warm. Frequently Aunt Hrana poured grains of incense on the charcoal, “to make the devils disappear”, as she said.

We listened carefully to Pavlos.

“My father was killed by the Turks”, he said with bitterness and indignation. “When the Russian army left the Pontos, we were left to our own devices again in February 1918. God had forgotten us then. I was seventeen years old. We remained at the mercy of God, in the power of the Turks. Everyone was starving. Many Christians became Muslims to satisfy their hunger. May God forgive them!”

“In the winter of 1918,” continues Uncle Pavlos and sighs, “the Turks gathered all men between fifteen and seventy. We were told we had to work for the state to build roads. We slaved from morning to night, had hardly any food and almost never a break. They wanted to kill us. We all knew these labor battalions were death squads.

Many Christians died building roads for Turkey. The roads of Turkey were the cemeteries of the Christians. God, let them rest! I found many bones on the side of the road and I was sure they were the bones of unburied Christians. So, I buried them.”

Through Uncle Pavlo’s reporting of human bones, I strangely overcame the thought of death and saw only skulls with hollow eyes, but they seemed so sad to me that I thought they were filled with tears of pain, like Yaya’s eyes. In front of me stood an unhappy man, but he had the strength to endure and survive.

“For endless months we worked hard with my father Theodosios and other Greek Pontians, breaking stones, cutting down trees, straightening the ground under the whip of the Chetes. My father was completely exhausted, so I worked for two. In the end, the Chetes were not to notice his condition. The work was barbaric and unbearable for weak and old workers, and for all those who could no longer work.” – “Every weak worker received so many lashes that his health deteriorated and he died. The dead man was then left lying on the edge of the unfinished road. After a year of uninterrupted, inhuman work, we had daily one or two, sometimes more, deaths.

As my father Theodosios confided to me one night, they had already done the same to us during the First World War: ‘They drafted us’, he said, ‘because we were Ottoman citizens, but we were not given weapons because we were Christians. They had us killed even though we were Ottoman citizens. We were second-class Ottoman citizens for them. They didn’t trust us.’”

“My father,” Pavlos continued, “has always slept beside me. When he still wasn’t awake one late morning, I touched him gently, but he did not answer. My next touch was more violent, but in vain. My father stopped breathing. He stayed there in the damned Erzurum.”

Erzurum, formerly Theodosiopolis, is a terrible symbol in Armenian and Greek-Pontic history. Here, under extreme climatic conditions with freezing winters and blazing summers, was a concentration camp for these former Ottoman minorities. It was here that the endless death marches began, leading to the forced labor battalions, which aimed at systematic extermination.

Pavlos continued: “’My father could not stand it, my father is dead’, I cried out to recover from the shock. I was inconsolable and began to cry. My crying was interrupted by a camp guard after a short moment. ‘Stop crying’, he ordered, ‘go to work!’ I followed the order, but returned immediately and asked the Turkish guard to give me my last money. ‘Bury my dead father so he won’t be eaten by wild animals, throw some earth on the corpse,’ I begged, suppressing my sobbing. ‘Allah will reward you!’ He promised me. I left him in the hope that my father would be spared the fate of the other dead Christians who remained unburied. The guard took the money, but did he keep his promise? I had done my duty. I swallowed my tears, crossed myself secretly – ‘May God put you to rest with those already killed’ – and wiped my eyes, splashed water on my face and returned to my forced labor, which I now had to continue without my father. The promise I had made to my father gave me wings and a great determination. The danger had lost its terror. The inhuman behavior of our Turkish compatriots had come to an extreme. We only had the choice of either staying in the labor forces until death or of escaping. Together with twelve other young men, the oldest was 26 years old, we ran away. We left the inhuman labor forces behind us and marched into the unknown. We followed the river all day. At dusk we reached a point where we had to cross the river. The group elder, Yacobos, felt responsible for us and led us.”

“But the unworthy river,” said Uncle Pavlos crying, “swallowed the unlucky Yacobos! He tried to find a passage for us and drowned in the process. There were many whirlpools, we learned later. The next day we decided to look for Yacobos. We had little hope of finding him alive. After many hours of searching we gave up hope. The commitment to our friend kept us trapped near the river. Unfortunately, we did not find Yacobos. We could not bury him and say goodbye to our brave friend.

The fear was great that the river would swallow us, too. We did not dare to cross it and thought of a less dangerous way. At night, when the bridge guard changed, we had to cross the river, which was at least as dangerous as crossing the river. We could actually pass the bridge while the guards were busy with the change. Nevertheless, they shot at us, but fate spared us. On the opposite bank we fell to our knees in relief. ‘God, let Yacobos rest in peace!’ we prayed. Then, according to our Christian tradition, everyone sang a death psalm.

After twenty-eight days we reached the village of a friend. Later, when I finally arrived in my village of Amrik (Ambrík; Tr: Ilecik), near Trapezunta, my mother couldn’t believe her eyes: ‘Embrace me!’”

Uncle Pavlos interrupted his report, wiped away his tears and sighed. We waited anxiously and held our breath. Our faces, marked by pain and hardness, were similar. We were a speechless, attentive audience. At one point I tensed my chest, my heart fluttered so much that it frightened me. I held on to one of Aunt Christina’s cushions and pressed it firmly to my heart. This calmed me down and I could listen again:

“Many months had passed since my arrival. We had not talked about Father at all, I had not told her anything, but my mother had not asked either. After so many years her heart is petrified, how could it not be! The tragic event had marked her life, she did not want to be remembered. She did not want to spoil her joy at my coming. She certainly felt that Theodosios, her husband, had sent her a great gift through me, her son. I cannot remember ever talking to my mother about my dead father. When I told her that I had given my last money for Father’s funeral, the petrified expression on her face became even more intense. I saw neither tears nor sadness on her face. She also showed no satisfaction with my behavior.”

Uncle Pavlos continued: “Hard, inhuman years. There was no time for tears. For years, all our villages grieved incessantly. Everyone waited his turn. Sadness, mourning, death marked our daily life in Pontos. We could no longer tell whose grief weighed more heavily. Our family was close friends with the family of a Turkish officer, in whose house I was able to hide for many months. However, my mother understood that the Turkish officer wanted to marry his little daughter to me, provided that I converted to Islam. My mother wasted no time. With the help of another Turkish friend, she sent me from Trapezunta to Constantinople with my cousins Joseph and Kyriakos.

Many Turkish compatriots in the region had not lost their humanity. They truly supported us and helped us secretly, because in every village there were Muslim newcomers from the Balkans and especially from Bosnia. They were Chetes and traitors. But our neighbours, these Turks, did not like the newcomers at all, although they were Muslims. We, on the other hand, were neighbors, friends and their Ottoman fellow citizens.”

He took a deep breath and looked at each of us: “In 1920 I arrived in a refugee camp in Piraeus on an Italian ship. I spent two years with relatives in Athens and at the same time I worked in the building trade. My mother Anastos came to Thessaloniki in 1922 with my brothers, Themistocles and Petros. They stayed there in the camp in Karaburaki. Unfortunately, our eight-year-old Themistocles died there. ‘My Themistocles had bad luck’, my mother often said, seemingly without pain. She had brought her stone from Pontos, I thought.”

Paradise… where Adam and Eve lived

Platania is a green village in Western Macedonia that is unknown to many. It is embedded between paradisiacal meadows. In his historical study, A. Adamidis writes that foreign archaeologists believed that the present territory of Platania flourished in Macedonian antiquity as one of the four then flourishing kingdoms on the right bank of the river Aliakmonas.

The climate of the village is determined by the wind coming down from the mountains of Kastoria, Grammos and Vitsi. In winter it blows mercilessly and hard. I remember how cold our noses were always. The summer is soothing and softens the unbearable heat. In autumn the wind comes like a capricious king showing his dominance. Then it brings rain, hot or cold air, often obstinate, it brings us the first light snow. In this way it clearly emphasizes who is in charge and dominates the climate of Platania. In spring he becomes cool like a noble knight and caresses what he finds. Gently he touches all the flowers and fills Platania with the rarest and sweetest fragrances. I wish all people, at least once in their lives, to experience Platania in spring in all its splendor. When it becomes spring in Platania, you can hear it. Every day, the most diverse flowers blossom and sprout, creating a new, enchantingly blooming landscape! Until today.

When I was an infant, I thought, no, I was pretty sure that the paradise where Adam and Eve lived was as beautiful as the blooming spring landscape of Platania. The sounds, tastes and air of Platania has its own fragrance, the most expensive fragrance in the world, because it is natural. The trees and the green of Platania speak only to us who know it.

The wind that comes down from Kastoria first caresses the huge Platanos, the leafy tree. Not only is it magnificent, it is also the one that gave our village its name. We always say Platanos and call it with a capital P, because it too belongs to the history of Platania.

This Platanos is the lord who stands as agerochos in the highest part of the village. From this position he controls and protects Platania and the Plataniotes. He knows everyone who has lived there for years before and after the exchange. He knows all of us who live now and will certainly know many generations to come. For the Turks who lived there and were forced to leave their homes and Platania in 1923, he was the Çınar; they loved him as much as we loved our Platanos. He has a big and tolerant heart, where there is room for all of us. He gives his shadow to all the inhabitants of Platania. He makes no distinction between the rich and the poor, the Turks and the Greeks. If we all lived together, he would certainly love us all and unify us. What the mighty of the world separate with their decisions, the soil and the roots of the Homeland connect. Its cavity was a playground for the Turkish children and since 1923 for the children of the Greeks from Pontos.

Strong feelings, pain and love, unite the two arch-enemies, the Turks and Greeks of Platania. Like two good friends or twins, one is able to understand the other. Their common love for Platanos, the tree, and for Platania is infinite and connects them. But uprooted trees die. Uprooted people cease to live. To become more sufferable, the pain of uprooting becomes a song. Like all expellees, they would sing together with all their soul the Pontic song: “Happy the one who dies on the ground on which he was born”.

Oriented on Platanos like a natural compass, English archaeologists carried out excavations in 1928 and 1929. The Platanos was the guide for the descendants of the Turks, who in 1975 visited the village of their grandparents, who had to leave their village in 1923 with great pain. The granddaughter of Feza, the Turkish village chief at that time, came to Platania to take earth and a certain spice from the yard of her grandparents’ house and from the hills of the village. This was the wish of her grandmother. She asked for an heirloom from Platania, a bit of earth. She told her granddaughter that she would take it to her grave:

“Go to Greece, bring me a bit of home, earth of Platania, to ease my grief,” she asked her granddaughter. Her story shocked me. I thought her granddaughter was knocking at the door of my conscience, when she asked: “Anastasia, did you bring your own grandmother earth from her home in Pontos?”

I heard the words of the Turkish grandmother: “My home is Greece and my village are Platania, my child!” I could understand that the village in Turkey where she was forced to live always remained strange to her. Proudly she wanted to show the homeland that was forced upon her, the earth of the homeland where she was born.

Platania was inhabited since 1923 by expellees from the Orient, from Pontos. Some of those who have lost their homeland live in Platania like my grandmother. Others were scattered and settled in other villages in Greece.

Platania is only a few kilometers away from Kastoria. From the café of uncle Dionysos and on the edge of the meadow you can see the lake of Orestiada, the lake of Kastoria. For my friends, for Anna and Marika and for me Platania is a paradise. It is a rare kind of warm nest. It is the whole world. I think of all the children in the world and I regret how poor they are that they did not have the luck to grow up in a village like Platania. To get to know nature, to play with pets or other animals. Run to the fields to cut flowers and fruits! To love the earth. To climb trees, apple trees, walnut trees, almond trees, pear and cherry trees. To climb Platanos and land on one of its big branches, to feel its tender warmth. This greatness of nature was our constant companion. Someone is at his place, says an Arab philosopher, if he knows at least two trees there. We three friends Anna, Marika and I know the Platanos and the pear tree in the meadow.

This pear tree and other fruit trees in the village and on the meadow were planted by the Turks. The exiles from Pontos loved and cherished the trees. Some were cut down later, others when they were too old or in the way of tractors and machines.

This beautiful village where I grew up has gradually lost its original appearance and beauty since 1960. The opening of the roads, not only in the village but also around the fields, destroyed the beautiful panoramic landscape of Platania. The wild roses in the alley next to our house were lost. The wild mirabelles were uprooted, the fragrant quinces, the blackberries. What happened? All together were lost and with them the natural beauty of my Platania faded. Every time something of Platania was lost or faded, I felt it uprooted from my heart.

In this once beautiful village, my good grandmother lived with the nostalgia of her own home and her own memories. Something deeper would connect us, which was unknown to both of us at that time. It was not only our parentage but also our common descent. It was the common fate of a forced journey we had undertaken.

I only understood that much later.

A grandma with crow’s eyes

After I finished primary school in Platania, I was twelve years old when I was recommended by a teacher from Samos, who was politically left-wing and therefore sentenced to prison, to go to secondary school in the small town of Argos-Orestikon. There I shared a twelve square meter room with two other girls with whom I had become very good friends. One afternoon after class I accepted the invitation of my classmate Iphigenia. “Shall we go to my house?” she asked with a smile. I was happy and assumed that I would be invited for lunch as well, because my food supplies had run out. Due to the flooding of the Aliakmon and Belos rivers that surrounded Platania, my mother had been unable to send the much sought-after carrier bag with food, cakes, boiled eggs, lard, chickpeas and black bread.

After six hours of lessons we were both hungry like wolves. Iphigenia’s family owned a beautiful house with a garden and like a traditional Greek family at that time, everyone lived together under one roof: parents, grandparents and children. When I entered the hallway of the house, the smell of food rose in my nose. “Granny, this is my classmate, Tasia[6]!” Iphigenia joyfully introduced me to her grandmother, but she was hard of hearing and asked several times: “Where is this girl from, Genna? – “From Platania”, Iphigenia repeated several times.

“Ah, from Bouboust? Ha ha! Ha ha! So, she is an Autissa[7],” she added.

“No!”, I answered categorically, not knowing what Autsa and Bouboust meant.

“I am Anastasia Kasapidou of Platania.”

“I know, I know,” said Iphigenia’s grandmother with her horrible crow’s eyes. “You in Bouboust are all Lazes,” she said. Another mistake – she called us Lazes, a Muslim South Caucasian minority that still lives in the Pontos area today.

The old lady knows a lot about Platania and the Plataniotes, I thought. It would be nice if she knew how hungry I was, too.

At my grandmother’s, there was always something to eat in case I brought a friend home.

Iphigenia’s grandmother looked at me, but I didn’t see any interest in her look, not even the slightest sympathy. She was just annoyed that her granddaughter had brought such a visitor from Platania.

“What a difference to my yaya”, I thought and suppressed my tears. I made an embarrassing move. I actually wanted to run away, but the smell of the food still held me captive. But then the croaky voice tore me out of my embarrassment:

“You must learn, Genna,” she said to her granddaughter. Then she turned to me and ordered: “And you’re going home now!”

So, she threw me out! I saw her crow’s eyes get even darker. My eyes burned from suppressing the tears, then I raced out. My fingers clenched in fists. I ran back to my room as fast as I could as if she was chasing me. Now that my classmate’s grandmother could no longer see me, tears were running down my cheeks. I had forgotten my hunger, but not this great insult. I fell face down on my bed and cried. The pleasant sleep helped me to forget the pain and my hunger. What did that old woman know about me? She did not even offer me a plate of food and not a chair so that I could at least sit down for a few minutes, as was always the custom with Greeks. Did she think I was not a good child or very different from her granddaughter?

If so, I wanted to shout at her: “Yes, you are different from my yaya!” There was a huge difference. Too bad I did not dare do it then!

In my grandmother’s house everyone was welcome, she had a good word for everyone and above all a plate of food, even for surprise guests. An archontissa[8] full of humanity.

I was very proud of myself for not crying in front of Iphigenia’s grandmother. I remembered the words of my mother: “Never show your hunger, be proud! Be humble, never say you cannot, you do not understand something, or you are hungry.”

We had to hold our heads high and were not allowed to show the slightest weakness. These principles of my mother made me very resistant to the harsh society of Argos and later in Germany. They strengthened me to clench my fists when necessary. This fist formed in Platania had turned to iron in Argos Orestiko. It was made of iron, but not heavy, so I always carry it with me. It is my pride and endurance in difficult situations and challenges in life.

I advise all mothers not to give their daughters a dowry, give them iron fists.

The nightmare of origin

Many in Argos Orestikon made me feel that I was not only different, but also inferior. In my childish understanding I wanted to change many things in this world. The first thing I would do was pass a law that said ‘diversity is legal’. Then I could proudly pronounce my name, Anastasia Kasapidou, without shame. The defining characteristic of man is his name. For years I could not say speak it freely because it betrayed my Pontic descent. Whenever anyone heard my name, it was immediately: “Ah, you are an Autissa!” or “ah, you are Laz!” The worst thing I have ever heard is: “When your people came from Pontos and Russia, they brought the evil communism with them!”

They gave me the nickname ‘aut(is)sa’”, because they were unable to understand the ancient Greek language, elements of which have survived in the Pontic dialect, and our pronunciation of the word ‘autós’ (‘he’ in English). In modern Greek, ‘autós’ is generally pronounced as ‘avtós’.

As soon as I mentioned my name, I was identified as the Autissa, the Laz, the communist, the Turkish brood. I hated my last name because it betrayed my Pontic descent. All surnames ending in -idis- or, for women, -idu (-idou) are of Pontic origin.

The trauma of these years is very deep; indeed, it has not healed. Until today many Greeks have not changed their contemptuous opinion about us Pontians, especially not the Greek politicians. I wanted to shout: “Yaya, if the people in your lost homeland were as unfeeling as they are here, if your homeland was as poor and not hospitable as Argos, you need not be desperate! Good thing you lost it!”

The second generation of refugees succeeded in overcoming the difficulties of the first. Pontic teachers were finally appointed. One was a philologist, his parents lived like all refugees in Tepe, a place in Argos Orestikon. This teacher was a second-generation refugee, an excellent student and a great philologist, but quite conservative, like most of the displaced people from Pafra (Turkish Bafra). The Greeks from Pafra in western Pontos were persecuted and massacred more severely than in any other area.

We talked and he analyzed the proximity of the Pontos Greek dialect to ancient Greek. He explained to us the Hellenism of Pontos and its history. Often with tears in his eyes he told us what he had learnt from his grandfather and his father. The Pontic dialect is ancient Greek and scientists have confirmed this. My joy was immense.

We are not a Turkish breed, as we were called. What a relief I felt! How much I want them to give me in writing what they say orally. Written proof I wanted, to prove the authenticity of my Greekness at all times. I was afraid that this evidence would eventually be taken back and I would have to experience the discrimination again. We are not Lazes; our dialect is close to ancient Greek. I do not have to defend myself and I do not live in a foreign, hostile country.

“Go, my child!”

The 15th of August was the day when the inhabitants of Platania met in their home town. In Platania, it marks the feast day of the end of the summer pasture, similar to the pilgrimage that once took place in Pontos with the destination of the rock monastery of Panaghia Soumela. All the Christians and Muslims of the area made their pilgrimage to this monastery to light a candle in honor of Our Lady of Soumela. In August 1969, I too, on leave from work in Kozani, went to the summer pasture of Platania.

“I will emigrate to Germany,” I confessed to my grandmother one afternoon when we were both alone. It was such a familiar, intimate moment, like when we were sorting lentils together.

“Why, my chickee? Where is Germany? Is that far away?” my grandmother inquired with a fright. “You have a good job here. You learn so many things at the doctor’s that you could almost become a doctor yourself. Don’t go so far away! You are a child and also a girl – and if you leave – when will you come back? Don’t forget I’m old!”

“I will go,” I replied firmly.

“Always be careful. Never forget the place of your origin,” she admonished me.

She told me not to forget my village. She used the word home only for her own place of origin, which was sacred to her. Like in a movie, her stories about home had passed my inner eye. Now I also wanted to leave my homeland. My grandmother had said herself that she was old now, but I convinced myself that she would live for many years to come. My decision was clear, this way should be mine. I had to free myself. When I revealed my decision to my mother at home as well, I expected to hear as usual: “You’re not going anywhere, you’re too young and you’re a girl.”

But she only just said: “Go, my child! It is not a state to live always in poverty and misery. You’re an adult now, and some day you’ll want to get married.”

Gotcha! So, my grandmother was worried about my wedding, how I would raise my dowry and pay the costs of a wedding. It was the unwritten law in those days. You were considered one of the lucky ones when a husband was found, whoever that might be. But my work with a microbiologist in Kozani had made me lose my reverence for the male sex.

In Germany

In October 1969 I went to Germany as a ‘guest worker’. I was one of many who filled the factories of Germany in those years. First, I was in Hilkerode, a town close to the inner-German border. Such places were partly abandoned by the GDR and the population was resettled. Zwinge, for example, probably owes its survival exclusively to the brickworks located there, whose products the socialist state of scarcity could not do without. However, the place was completely sealed off from 1966 onwards and could only be entered with special permission. Only since the reunification of Germany in 1989 has the village regained its importance in a central location in the southern Harz. However, the brickyard, once so vital for survival, was closed down and demolished in 2012, and a solar park was built there.

Hilkerode is a small town near the border to the former GDR in the immediate vicinity of the university town of Göttingen and right next to Herzberg, the birthplace of Queen Friederike. As a result of the Second World War and the division of Germany, I heard the same stories here as in Platania: stories of the lost Homeland, of separated, broken families and of the Berlin Wall, which divided families, friends, relatives and the entire German people. Families and friends were separated. Some, like my grandmother, lost their homeland, their siblings and their children. To me the whole thing seemed very unjust. Instead of punishing the Nazis and carrying out a real denazification throughout Germany, families were separated from each other.

The GDR was not far from the place where I worked. We reached the border from Hilkerode on foot. In 1969 I took a walk and saw the town of Zwinge, which was close to the Iron Curtain, up close. Through all the things I had heard over the years, the image of this Iron Curtain had become a desolate place in my imagination. But this beautiful small town with its countless green spaces could not be the Iron Curtain! We were informed that the city had remained as it had been before the war, as it was an industrial city. Bricks were produced there. All villages and towns near the western border were depopulated. Zwinge remained an exception. Everywhere this political system built walls at the border to separate people from each other. Only in Hilkerode did I realize that Berlin was no longer the capital of Germany. Bonn was the new capital of West Germany. Germany had lost the Second World War and should be punished. It is hard to believe that Turkey remained unpunished when it, together with Germany and others, had lost the Great War, as the First World War was then called, not only in Platania.

Greece pursued a much harder and more inhuman path after the Second World War. People were declared good or bad citizens. In 1949 the Greek people were divided into communists and those conservatives, ‘proud of their nation’. The partisans who had fought against fascism were expelled to the countries behind the Iron Curtain because they were considered dangerous for Greece.

As if all this were not enough, they were also deprived of Greek citizenship. To date, no political party has apologized for this action. When the expellees were allowed to return, many did not want to return. Their Homeland was lost to them forever.

Now that I was in Hilkerode, these thoughts circled in my head again and again and tormented me. The first months in Germany Hilkerode were indeed extraordinary for me. I had my freedom, but I felt lost. I was downright disappointed and could not enjoy my newly won freedom. Something prevented me from doing so. It felt like the people who, after years of dictatorship, could no longer get used to democracy. It was only many years later that I realized that the democracy that we were allowed to live so intensely in post-war Germany was a gift from God for all of us.

The sun, which accompanied me every day in Greece, was unfortunately always missing here. But it was a pleasant hope and joy to have a full wallet every month. The wallet with my own money filled me with confidence and made my imprisonment in an unknown place more bearable. When I received my first wage in an envelope, the joy was as great as if I had found Aladdin’s treasure. I sent 200 DM to my parents and kept the rest.

A Greek woman helped me with my first food shopping. Hilkerode had a grocery store where the food on the shelves was so perfectly arranged that I was afraid to touch it. Finally, I managed to buy a large box of chocolates and a jar of pickles. I thought, in this country, there is nothing to eat. Now I had so much money to myself and yet I could not find anything to buy. And what frightened me even more was this silence and peace everywhere. The silence and order reminded me of my home and annoyed me. As if they had all taken lessons from my mother in Germany. And where did my mother get that from?

The City that Reminds me of my Grandmother’s Home

Like the migratory birds that leave the north in winter, I left Hilkerode to move south without even really knowing it. To be closer to my Greek homeland, I thought satisfied. Since 1970 I live in Munich and work for the company SIEMENS. No comparison with Hilkerode! Munich, also called the Isar-Athens, has something Greek about it. A beautiful large city on the Isar with a taste for beauty, emphasized by the Propyläen, the Glyptothek and the Pinakotheken, the wide Ludwigstraße, the Königsplatz and much more. After the shock of the first few months, I have redefined myself in Munich.

SIEMENS needed many workers at that time, including women. I worked in a pipe mill. A spectacular room full of young women. Most of the female workers came from Turkey and Greece. My Turkish work colleagues are very kind and have nothing to do with the Turks who expelled my grandmother. They have a lot in common with us Greeks, especially with the Greek women from Pontos. I have also made some great friends. With one Armenian woman I had a special long-standing friendship, because we shared a common history. The stories she told about her grandmother were similar to those of my Yaya.

I remembered my mother who forbid us to learn and speak Turkish or Pontic Greek, this allegedly corrupted the Greek language. In this respect my mother was not right. The narrow-minded Greek society forced her to forbid us both languages. The Greek aristocrats only learned French at that time, and I too had French for three years in Argos Orestikon. Nevertheless, Platania’s sounds very soon helped me to learn Turkish. I spoke and understood Turkish very well after only one year. Instead of learning German in the first year in Germany, I learned Turkish without listening to my mother’s ban.

The SIEMENS houses in which we lived were purely guest worker accommodations. It was a multicultural working-class apartment building, a simple dwelling for the needs of its international residents of various ethnicities, which certainly none of us who lived there will ever forget. While we lived there, we all met together in the courtyard. There I heard many different melodies and also the wise men whom my father so loved in Platania. The Turkish roommates listened for hours to the songs of their home country, they were nostalgic like all foreigners and hoped to return to their homeland one day. In Munich I also met some Islamized Pontos Greeks from the Black Sea region who were still aware of their origins. Some spoke fluent Pontic Greek. Many continued to visit the Panaghia Sumela monastery. They danced the same dances as us and with us. My whole interest was in work and the Turkish language. I also learned some scattered words in German, the first thing I learned was the word ‘Akkord’ (contract work) on the assembly line. The Turkish friends and my Armenian girlfriend became a bit like home for me.

I was not looking at the suitcase with the clothes, but at the other, invisible luggage that I kept deep inside me: Mother’s advice and above all the precious agreement I had made with Yaya. This Greek origin tells me to put down roots in Munich, and I want to do so. I wish only one thing, that the wind of Platania touches and embraces me all seasons and mixes with the wind of Munich. In Greece, my life was determined by teachers, parents, priests and dictators. In general, they were conservative and full of prejudices. Today I live with my family in an apartment near the North Cemetery. When I walk through the streets, in the shade of the plane trees, I feel like I am under the trees of Platania.

When I look towards the cemetery grounds, I think that Yaya, Uncle Vasos and all my beloved dead from Platania are speaking to me. A bridge connects my chosen homeland with Platania. I have been writing for a long time. It gives me life and an indescribable joy. I am then with my thoughts in all nooks and crannies of Platania.

Here in Munich, where I live, I have my Greek Orthodox parish church nearby and can live out my freedom and both, my attachment to Greece and my Pontos-Greek identity. I am grateful to Germany for this. Here we Pontic Greeks have our association and can engage ourselves politically.

Legacy and mission

In the summer of 1974 Platania seemed cold to me. Yaya was very sick. Cirrhosis of the liver was the diagnosis. She had been infected by the animals she kept at home. As she lay on her bed, she had shrunk to a small pillow, as they say in Greek. As soon as she saw me, she cried out: “Oh, if you were here, my chick, I’m sure I’d get well very quickly!”

Yaya was sure that if I did not go to Germany, I would be half a doctor, as she predicted when I left Greece in 1969. How much I loved my good grandmother, this pure soul! I had great trust in her. For a moment I reflected with her about my childhood in Platania. I would have loved to ask her: “Yaya, what else do you expect from me? Sure, Yaya, I thought I was close to you, but I certainly could not cure your illness. But you can be sure of one thing, I have not forgotten our agreement and will write everything down.”

I didn’t mention any of this to Grandma. Those memories would have crushed her shrunken body. I remembered what she had always told me: “Don’t forget what I have told you all these years, follow the advice! One day you will surely return to Greece, you must not die in a foreign country. But respect the whole world, especially those who give you work.”

I will only respect those who deserve it, I thought. It would have been clumsy to share my liberated thoughts with my grandmother. She could not understand what I mean and would not change her attitude anyway. Times have changed.

I have been working for many years to write about the history of the displaced people of Platania.

The respect for the people, the love for their origins and the fate of the Pontos Greeks in general drive me forward and give me strength.

The Pontos and its culture have now become a concrete idea for me. Nothing should be lost, otherwise Yaya would be lost for me. Also, I will not forget anything, because then I would forget Yaya. My grandmother is so intense in me, so strong, she is always present and restless, as if she were waiting for something. She always leads me and pushes me: “You have come, my chick”, I hear her say to me.

Summer 1977

In May 1977 Yaya died, she had become well over 80 years old. Only in August I could come from Germany to Platania and visit her grave. Platania, which had never become Yaya’s home, now seemed so silent, cold and frozen to me.

My grandmother’s life was only determined by her Pontos homeland. Platania was just a temporary solution for her. What had she always said? “I am not a potato that they pull out in Pontos and put back in Platania.”

I would never be able to visit Yaya in her house again. Her death left a very big void in my life. I saw her slippers standing in a corner of the corridor, saw her walking with them. The tears running down my cheeks were hot but liberating. Olga, my sister, caressed me. “Don’t cry,” she whispered, “in the end we all took care of her with love.”

I wished that God would not disappoint her this time. If I could only turn back the heartless and hard time and change it! At the end of her life, her bitter soul had little strength! All she could think about was Vasos. The countless dead in the lost homeland, she had forgotten them all or left them to me, I wondered thoughtfully.

I left Yaya’s empty room and walked up the road to the cemetery. The funeral of Uncle Vasos, which I attended on this hill when I was ten years old, ran before me like a movie. I cried very loudly. I was alone, nobody heard me. I stood like a column in front of my grandmother’s grave and squeezed my eyes together in front of her picture. Next to her was the picture of her beloved Vasos. My hand trembled when I lit the candle at her grave. “Good luck in paradise, Yaya”, I moaned. I didn’t need to say anything to Uncle Vasos this time, he was no longer alone, his mother was with him now.

Yaya died with her eyes open. Did the eyes of her soul look towards Pontos and her Koronixa? I am sure that her soul got wings and she went home first. I felt the pain in my heart and clenched my fists.

“Yaya, I will visit Koronixa to bring you home soil for your grave. I will also pray to Panaghia Sumela and light candles for your dead!” I promised her. I have written down your fairy tale story for my descendants. Before Yaya’s grave I experienced something that I can neither describe nor record: Homeland, haunted life, grandmother’s voice, all a burden, and the journey of her life. You only understand these things when you experience them.

“Depositum”

I do not write literary short stories and novels. Nevertheless, I wanted to write about the tragedy, about the open wound I was born with and which still bleeds today. A trauma that will occupy generations to come. I would like to describe the pain, the story, the words of so many people who still haunt me today. All words have priority. First Yaya’s generation, followed by my parents and my own experiences. They are all eyewitnesses and give an authentic testimony of history. Yaya’s fairy tale-like narration comes first.

I call them fairy tales, because their words often went beyond the tangible and human, and ‘history’ because this river that has carried and tormented so many human lives is true! Those who told it had no political influence and served no interests, nor did they want a reward.

Everything I heard and experienced as a child of refugees and poor leftists is a different school. In this school the subjects lead the people through daily exams: Humanity, struggle, justice, survival, bitterness and tears, effort in search of truth, humiliation, iron fist, success and happiness!

Despite all my tragic life experiences, the fairies have given me a lot of luck in the cradle and opened the way for me to live as I live today, in Germany, in my Munich. In this city I came into contact with Greeks from all parts of Greece. In Munich I got to know almost all nationalities of the world and so I got rid of my own prejudices step by step. The wall that darkened my mind and made me not think clearly fell. And I wish that everything that separates the peoples from each other may fall.

We should have the chance to see more walls fall than the Berlin Wall. I wish that the wall that divides the Cypriot people will fall and the wall that darkens the Theological Seminary of Khalki[9] will fall.

Perhaps I unconsciously chose the city of Munich so that my voice could be heard. Here people from different cultures and peoples live together as in the place of my ancestors. Perhaps Munich resembles my grandmother’s Homeland in Pontos, where different nationalities lived together: Armenians, Assyrians, Kurds, Turks, Circassians, Lazes. But later I made a conscious decision to stay in Munich. I love this city, my home, my adopted country.

In my years outside Greece, the suitcase with Yaya’s words and advice has always accompanied me. The suitcase also contained my political ideals, which I painfully lost in 1978. That year I travelled to Poland for the first time with my Munich friend and neighbour. In the small village of Kroscienko we visited her father, who unfortunately had to live in the most miserable circumstances, and I met Greek political refugees who had fought against German occupation in World War II. They literally lived in huts and had hardly anything to eat. It was incredible for me. During my visit to this country behind the Iron Curtain, I cried bitterly from the bottom of my heart because I had lost my political ideal.

I also realized why, paradoxically the Greeks did not hate the Germans after the cruel Nazi occupation. The devastating civil war, even fratricidal war, with more victims than in the whole of the Second World War, has left deep wounds in the Greek psyche. Again, I looked at Yaya’s suitcase, on which was written: “You must not forget the injustice!” This injustice finally made me realize that neither prayers to God and Panaghia Sumela, nor a political party can save us from the dilemma. Only with other organizations that serve true human rights, not through political parties and politicians, could it be achieved. The Greek people were deeply hurt in their cultural roots, their intellectual and historical resources were wounded and exhausted. This slowed down further development. For certain reasons, the wounds have not yet healed: The history of the Greek nation has not been properly and completely taught, one could say it has been struck by a collective amnesia.

Greece has still not recovered from the trauma of the Ottoman genocide, paraphrased in history books as the Catastrophe of Asia Minor. In my opinion, it was a tragedy, not a disaster, that is to say not a natural disaster such as flooding or an inevitable fate such as an epidemic. It was the heavy burden of division that caused displacement and uprooting. I wish that the Greek people could return to their origins, to their deep-rooted moral and social values.

Between 1996 and 1999 my life, like that of many other foreigners living in Germany, changed. My heart turned to stone when I heard slogans like ‘Foreigners out’ and neo-Nazi groups harassed and abused foreign born fellow citizens with the pale excuse that migrants were taking their jobs away from them. At that time, I risked losing my beloved Munich, but Yaya’s image and her lost homeland came to the fore like a warning. I was present at all the demonstrations and light chain vigils to defend my adopted home.

In Germany, the word ‘integration’ is currently fashionable. When I came to Germany in 1969, no one was interested in it. There was no talk of the integration of guest workers. Now politicians are trying to compensate for their omissions of the past and integrate foreigners by law. Fortunately, with the help of my husband, who comes from the Rhineland, I succeeded in integrating myself in Munich. My conclusion about integration: If we do not get to know and process our history properly, if crimes against humanity are not prosecuted and punished and generations of people have to live with their traumas, if politicians do not take this seriously, integration will not succeed in any country in the world.

Listen, my little child!

“Ivi, my little girl, my sprout! Your name means eternal youth. When I was young, I tried to understand the world and I asked God to make up for the injustice that happened to my grandmother and the people in my village. Now you are near me while I try to write down everything I have heard and experienced. That’s how I walked around my grandmother’s feet! My dear Yaya spoke to me, and I listened…

‘Listen, my little child, my chick! You won’t forget’”…

It is autumn, the plane trees on the Berlin street have thrown down their leaves here and there to cover their roots. In the play corner my granddaughter Ivi is having fun.

“You came to me, my chick,” I whisper as I look at her. Yes, my ‘little flower’ is with me very often, I still tell her fairy tales and sing songs for her. Later I have to tell her a lot about dignity and abilities and how to make an iron fist.

I wait until she is 15 years old, then I tell her, my chick:

The resolution that passed the Bundestag on June 2, 2016, contains, as I assume a hierarchy of victims, led by the Armenians, followed by the Arabs, Assyrians and Chaldeans. Not a single word about the hundreds of thousands of genocidally murdered Ottoman Greeks, including 350,000 Pontos Greeks. That hurts and diminishes the value of this parliamentary recognition, whose authors seem to have turned a blind eye to the true dimension of the crimes committed against the Christians of the Ottoman Empire before, during and after the First World War.

Since June 2, 2016, another sentence that I heard at that time in the German Bundestag has haunted me: “…to the Armenians, the Assyrians, Aramaeans, Chaldeans and the OTHERS”. The anonymous Others, that is us: the Greeks – from Pontos, from Cappadocia, from Eastern Thrace, from Ionia. And in the chronology of these state crimes the Greek Orthodox Christians were the first victims.

After the Second World War, the Germans learned that the path to a reconciled future with the peoples of Europe can only be taken at the price of critical examination of the darkest chapters of their own history. I have respect for this, and even though I am bitter that the Pontos Greeks were not mentioned by name in the 2016 resolution by the German Bundestag, I think that such a resolution was important in principle and overdue after one hundred and one years.

After this first major step and in view of the growing interdependence of peoples, I appeal to Germany to face up to the questions and interrelationships arising from it and finally to take the step of demanding that a state like Turkey faces up to its historical responsibility.

“Please help us to make the border between Turkey and Greece like the border between France and Germany.”

This is the mission for you and your generation, my dear granddaughter IVI!

You must not forget our countless dead! Maybe when you grow up, you will be able to light a candle for them.