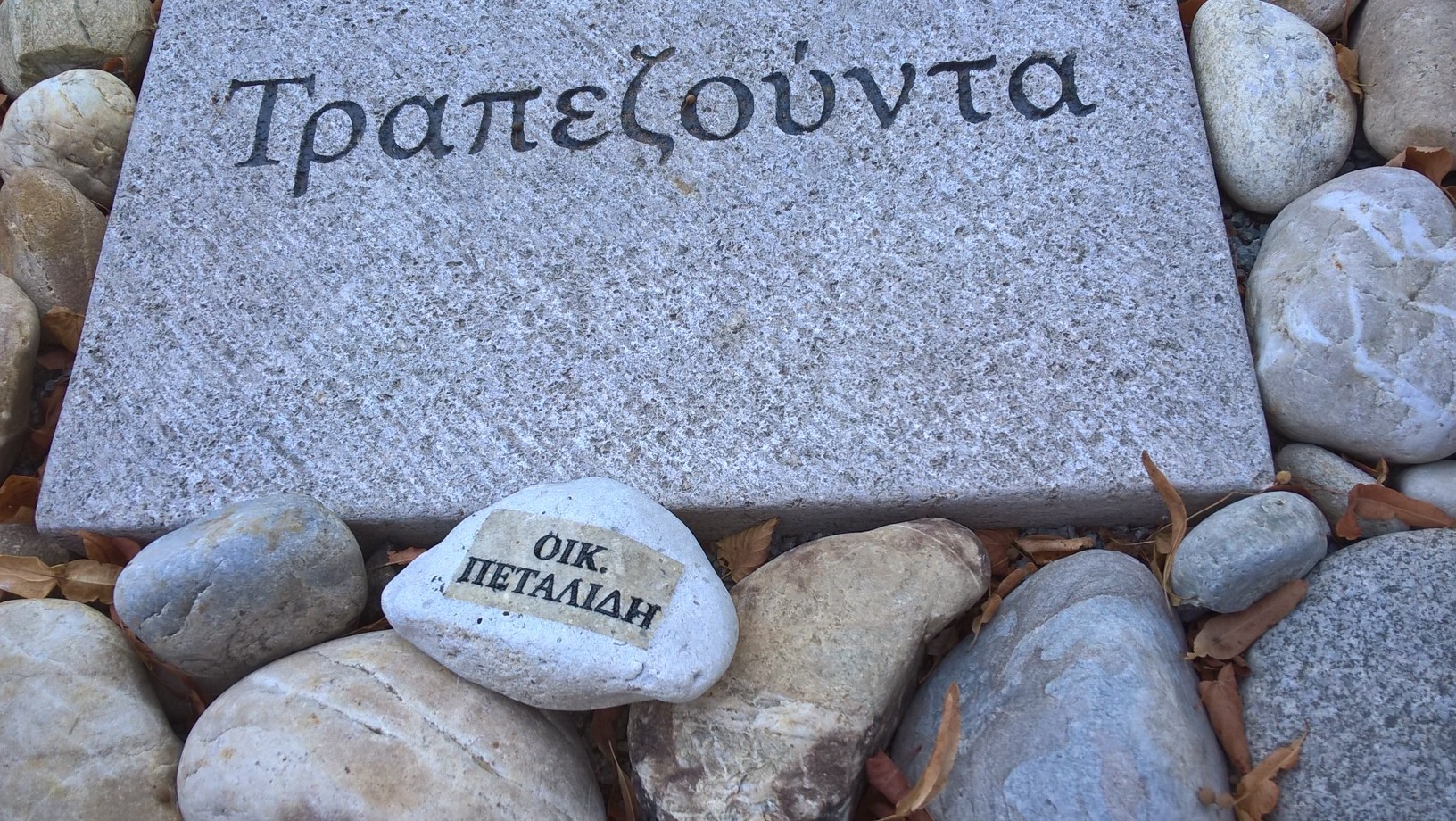

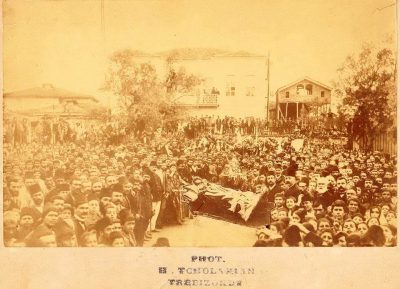

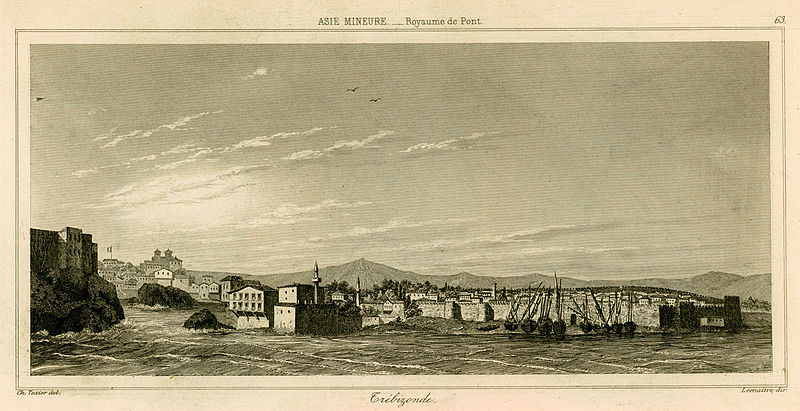

The City of Trebizond / Trapezounta – Τραπεζούντα in the early 19th century

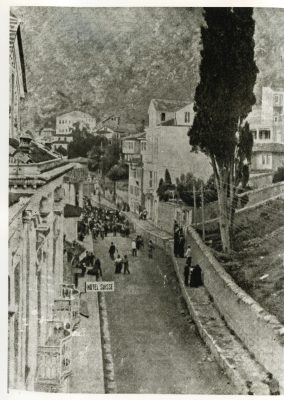

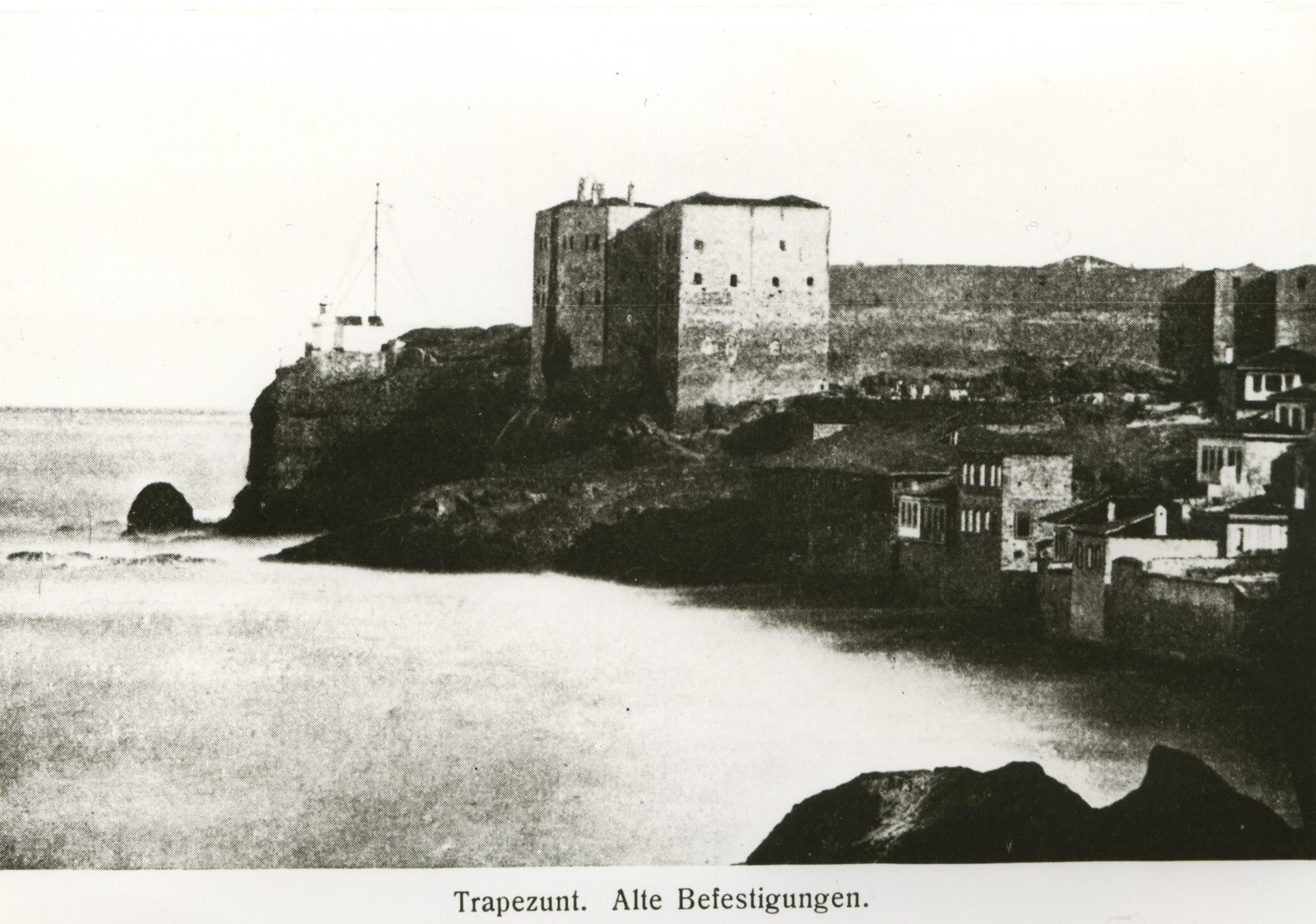

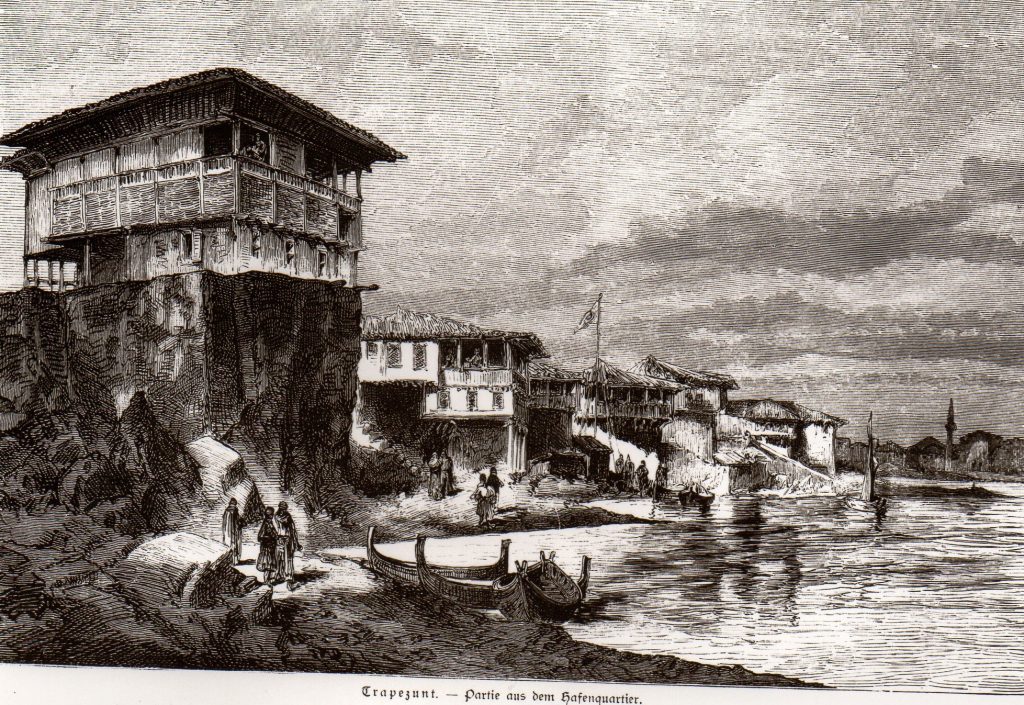

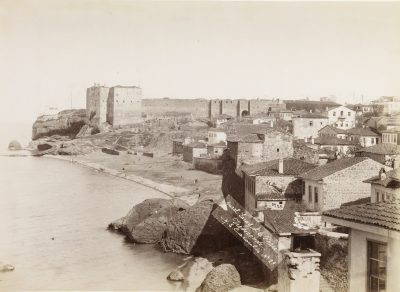

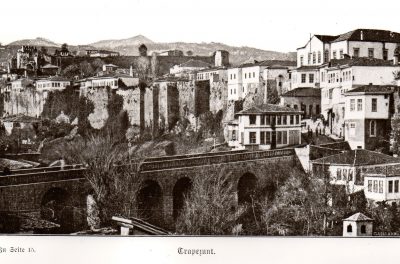

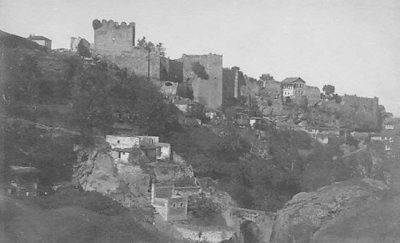

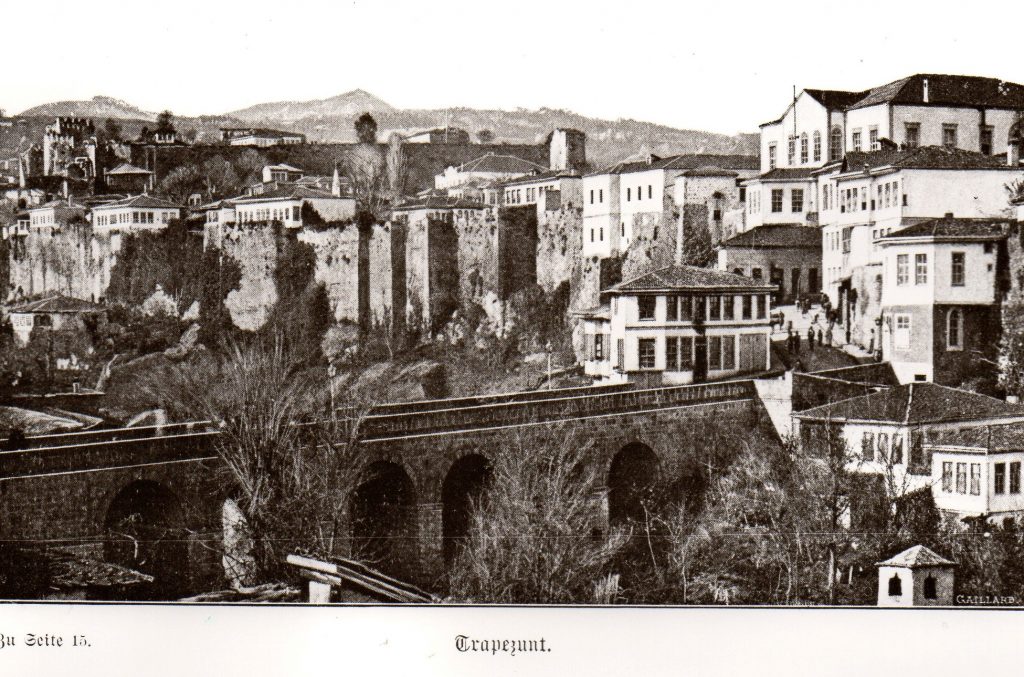

“(…) I observed a large church, now converted into a mosque. We traversed number of narrow dirty streets, and afterwards ascended into the citadel, which is situated at the southern extremity of the town, and commands a full view of the city and its environs. Trebizond is of an oblong shape, the longer sides running parallel to from S. to N., and occupying a slope gently rising from the sea: on the E. and W. it is defended by two deep ravines, which are connected by a ditch cut in the rock behind the castle, and on the W. an outer work has been carried from the tomb of Avia Sophia to the shore. The ancient ramparts of the city, which are built in the stone, and in general very lofty, run along the skirts of the ravines above mentioned, washed in the N. by the waves, and connected on the S. with the citadel: there are six double gates, and over that of Erzeroom [Erzurum] is a Greek inscription, which I found it impossible to copy, from the great number of Turks continually hovering about the spot. The houses, for the most part, are built of stone and lime, roofed with small red tiles, and like the common Turkish dwellings, mean in their outward appearance and comfortless within.

We again quitted the city by the gate of Erzeroom, and crossing the bridge built over the ravine on the eastern side, entered a large suburb, chiefly occupied by the Christians, and which, from the number of old churches and other edifices it contains, most probably composed part of the old city. We were then conducted into a small meadow, surrounded by houses, and called Gour Mydan [Gavur Meydan], or, Infidel Square, as being the quarter of the Greeks (…).

This is a very ancient city, and mentioned by Xenophon in his history of the retreat of the Ten Thousand, under the appellation of Trapezuz, a name, which is acquired from its resemblance to the geometrical figure of that denomination: it was, according to the Grecian historian, a colony of the Sinopians, well inhabited, and situated on the Euxine Sea, in the country of the Colchians. It subsisted as a free and independent city until it fell under the dominion of the kings of Pontus, from whom it was conquered by the Romans, and included in their empire, as the capital of the province of Pontus Cappadocius. In the year 1203, when Constantinople was taken by the Franks, Alexius Comnenus established an empire which extended from the mouth of the Phasis [today Rioni] to that of Halys [Tr: Kızılırmak]: four princes of this house reigned under the denomination of dukes, or emperors of Trebizond, until their final expulsion by Mahomed II since which time the city has remained in the possession of the Turks.

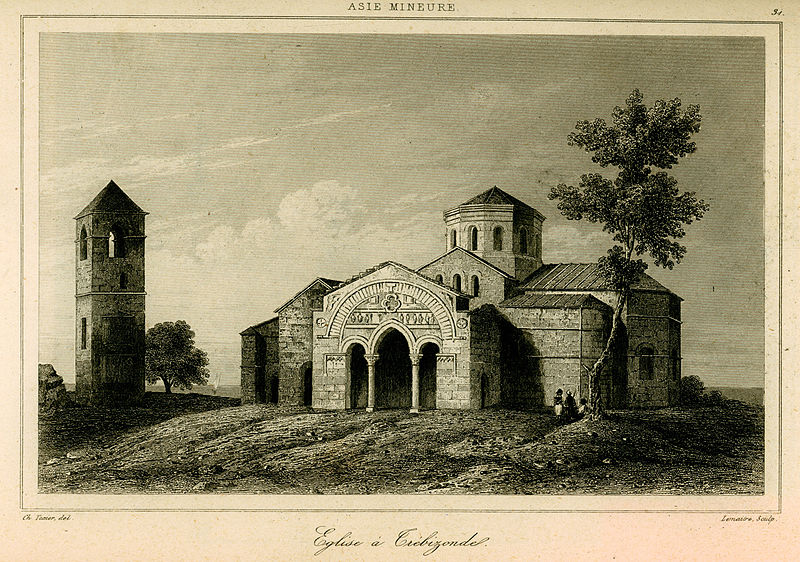

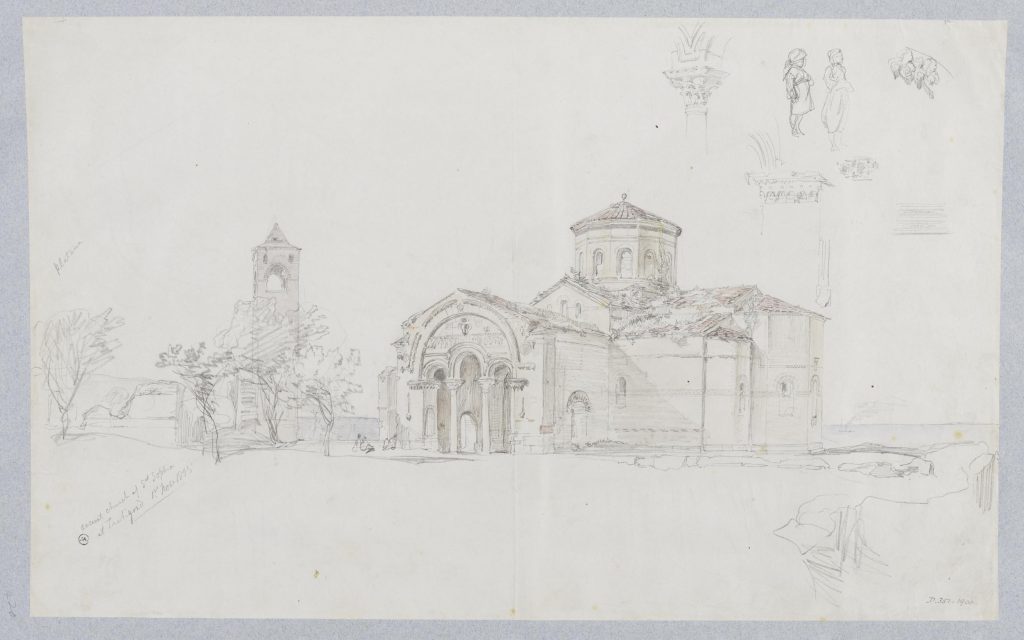

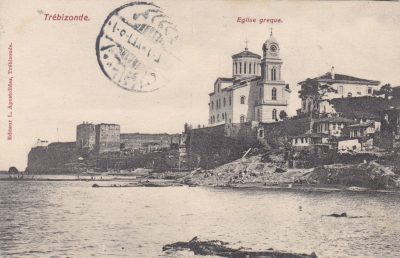

Trebizond is said to contain a population of fifteen thousand souls, a heterogenous mixture of Turks, Greeks, Jews, Armenians, Georgians, Mingrelians, Circassians and Tartars [sic!]. The trade is very considerable, and the principal exports are silk and cotton stuffs, manufactured by the inhabitants, fruit and wine: the imports are sugar, coffee and woollen cloths from Constantinople, salt and iron from the Crimea and Mingrelia. There are eighteen large mosques, eight khans, five baths, and ten small Greek churches, governed by a despot or metropolitan, and built on the same model as that of St. Sophia (…).”

Source: John Macdonald Kinneir: Journey through Asia Minor, Armenia and Koordistan in the Years 1813 and 1814; with remarks on the Marches of Alexander and the Retreat of the Ten Thousand. London 1818, p. 339ff.

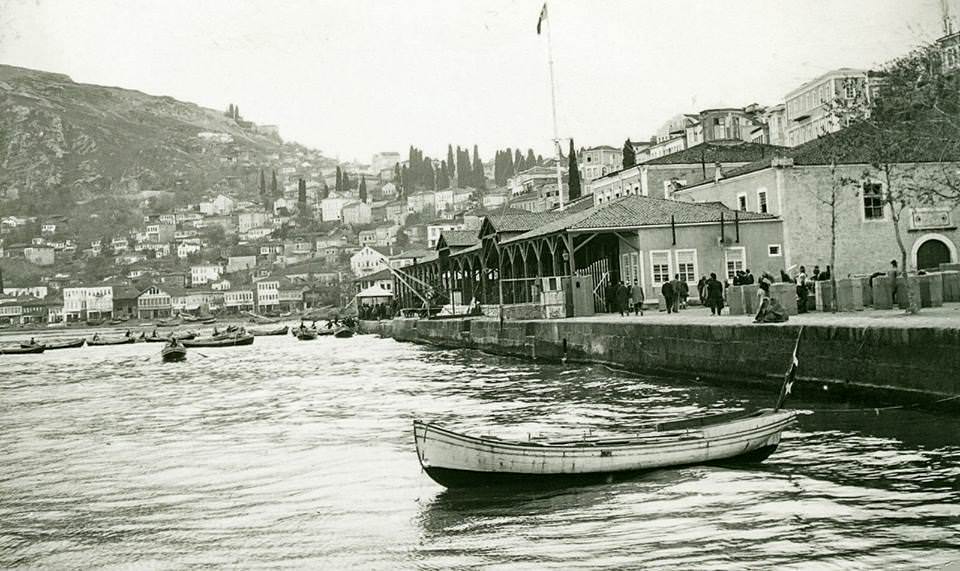

H.T.B.Lynch: ‘Queen of the Euxine’: The City of Trebizond / Trapezounta / Trabzon

The appearance of the city in the days of her splendor must have justified her reputation as ‘Queen of the Euxine,’ and lent color to her claim to be the capital of a restored Roman Empire of the East. Between extensive suburbs, filled with busy streets and markets, rising from the shore on either hand, through a labyrinth of gardens and garden-houses, clustered on the higher slopes, the two converging lines of massive parapets and towers mounted slowly up the shelving ground. The further they receded from the margin of the seaboard, the clearer grew the essential features of the site – the ravines opening darkly at the irregular course of the chasms, and now rising, now declining, along the uneven surface of the cliffs. Near the head of the figure stood the royal palace, raised high above the massive works of the citadel, deeply moated by the sister gulfs on either side.

Broad windows opened from the royal reception hall of with marble to the varied prospects on every side, while within, the vast apartment was adorned with rich paintings, the portraits of successive holders of the imperial office, their insignia and arms. On the east, beyond the abyss, the slope gathered gradually to the side of Mithros, the table-topped hill, in which direction, just opposite the palace, the church and fortified enclosure of St. Eugenius (Evgenios) crowned an almost isolated site which was flanked on the further side by a third and lesser ravine.

Towards the interior, on the side of the narrow isthmus, the view ranged wide, above the battlements, over the hills encircling the broad bay; while the rising ground, opening upwards from the tongue of the isthmus, was occupied by the theatre and by the extensive walled enclosure of the polo-ground or hippodrome. A royal gate gave access from the palace to these pleasure-places, the distance of a short walk from the wall; and through this gate the imperial party and their brilliant court would pass to their marble seats above the race-course, whence the whole landscape of the city and field and ocean lay outspread at their feet. (…)

Among the most pleasing and perhaps, not the least striking feature in the composition of these scenes must at all times have been the luxuriance and variety of vegetation which is natural to this soil. The necessary moisture is provided not by stagnant pools and marshes (…), but by salubrious springs, bubbling from the surface of the rock and collecting in rustling streams. The sun is indeed the fiery orb of the Eastern landscapes; but the climate is tempered by the chilling winds from across the sea, bringing rain and mist in their train. The outcome of these conditions is the simultaneous exuberance of the trees and plants which flourish upon the coasts of the Mediterranean and of the leafy giants of our Northern woods; side by side with shady thickets of chestnut, elm, oak and hazel, groves of cypress, laurel and olive grace the shore. The wild vine hangs in festoons from the branches, and in sheltered places the orange tree, the lemon and the pomegranate thrive and yield their fruit. All our fruits are well-stocked gardens, while the fig of Trebizond is of old as famous as the grapes of Tripoli and the cherry of Kerasun [Kerasus; Tr.: Giresun]. Cucumbers are cultivated, and heavy pumpkins, and tobacco, and Indian corn, with its reed-like stalks and luscious leaves. The beautiful pink flowers of the oleander may be seen rising above some orchard wall. In the middle of the seventeenth century we were told of upwards of thirty thousand gardens and vineyards inscribed on the city registers (…).

Quoted from: Lynch, H.T.B.: Armenia: Travels and Studies. Vol. One: The Russian Provinces. Third Printing. Beirut: Khayats, 1990, p. 17f.

The Greeks of Trebizond: 16th-20th Century

Historically known as Trapezus, Trebizond and Trapezunda by Greeks, the city of Trebizond in north-eastern Turkey boasts a rich Hellenic past. It was founded by Greeks in the 8th century BC and existed as a colony of Sinope. (…) Trapezunda rose to be an important city in terms of trade during the time of the Roman Empire; its position allowing it to benefit from trade between Persia and the European provinces of Rome.

(…) From 1540, Constantinople was the main destination for Greeks who wanted to leave the shores of the Black Sea (especially Trebizond) seeking better working and economic conditions. Those who lived further south in the interior of Pontos found this journey more difficult so they tended not to take the long and tiresome journey.1

Almost immediately after the fall of Trebizond to the Ottomans, many Greeks fled to Constantinople, to Iberia in Western Georgia, and to the inland of Pontos. Churches were turned into mosques, the palaces of the Comnenoi rulers were taken over and became the home of the new Turkic rulers, and the remaining Greek population was forced to live outside of the city in close proximity to the church of Saint Sophia.2 The Greeks were also banned from crossing the walls and entering into the city.

In 1665, a horde of fanatic Turks raided the district of St. Phillip forcing the Greeks out of their homes and subsequently taking over the church which they turned into a mosque. The Metropolitan (priest) managed to survive the rage of the Turks and fled to the church of St Gregory of Nyssa which subsequently became the new Metropolitan church of Trebizond. The remaining Greeks of St. Phillip fled to the neighbouring region of Tonya where they were later forced into Islam, a common practice during Ottoman times. During this period, wealthy and influential Greek families of Trebizond such as the Mourouzis, Ypsilantis and Rizoi families as well as others, fled to neighbouring Russia or Constantinople.3

This general persecution of the Christian Greek population of Trebizond was to continue until the Tanzimat reforms which were implemented during the period 1839-1876. A series of reforms in 1856 known as the Hatt-ı Hümayun promised full legal equality for citizens of all religions. The Greeks were finally able to conduct their day to day lives as equals, and in the coming decades benefited from it.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Greeks of Pontos owned buildings and assets of enormous wealth. They owned 37 formal philanthropic and cultural foundations, 1047 schools (primary and pre-secondary), 10 secondary schools (comprising 1236 teachers and professors, and 75,953 students), 22 monasteries and 1139 churches under the direction of 1459 priests.4 Much of this wealth was centered around Trebizond.

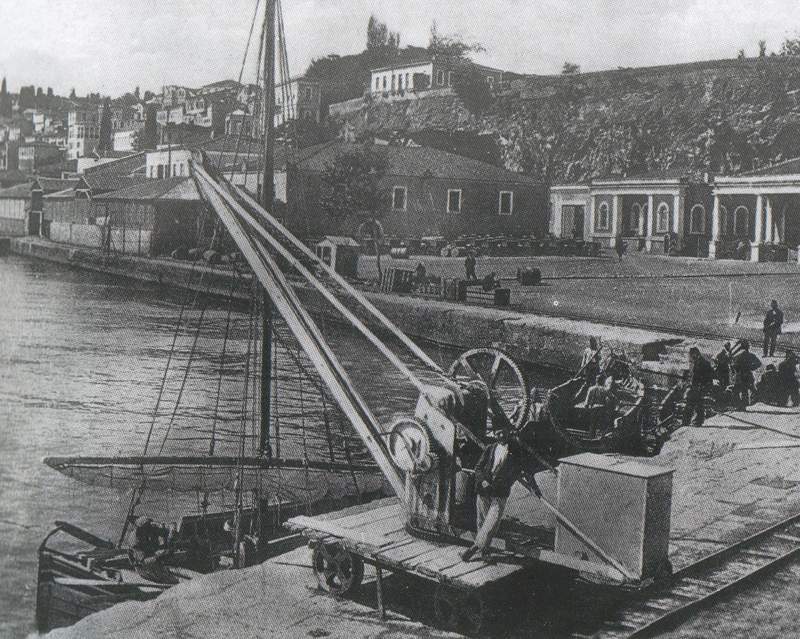

According to figures collected by the British consul, the volume of shipping clearing the port of Trebizond rose from an annual average of 15,225 tons in the early 1830s to annually 61,664 tons twenty years later and from annually 177,861 tons in the early 1870s to annually 483,732 tons in the early 1890s. By 1882 the steamships of 5 different companies called weekly at Trebizond.5 The Greeks benefited from this increase in trade and by the early 1900s had increased their wealth considerably. Three of the five banks in Trebizond in operation were owned by members of the Greek community: the Bank of K.Theofylaktos, the Bank of Kapagiannidis and the Bank of Fostiropoulos. The fourth bank was a branch of the Ottoman bank and the fifth was a branch of the Bank of Athens.6

Greeks were also influential in public life. They took part in political administration, judicature, finance, agriculture and technical works. In the courts of first instance, appeal and of commerce there was one Greek in each section. In finance they worked in tax collection, the estimates committee, tobacco monopoly, Ottoman and Agricultural Bank branches, and public debt administration. In education they were sometimes employed on the education committee and in secondary schools. They were important contributors to engineering and public works as engineers and the postal and telegraphic service as operators.7

The Greeks of Trebizond became renowned for building numerous churches, some of which are still standing today. Saint Sophia which was built in the 13th century is perhaps the most notable Greek Orthodox church. The Greeks also built numerous buildings in the city. The Atatürk Kiosk (Pavilion) is in fact a building erected in 1890 by wealthy banker Konstantinos Kapagiannidis. The Trabzon Museum was built in the early 1900’s by banker Kostantinos Theofylaktos. Another notable building is the Trapezunta Tuition Center (Frontistorion Trapezuntas) which was founded in 1682.

According to Brant, the British consul at Erzurum, the population of Trebizond in 1835 was between 25,000 and 30,000 inhabitants, 3,500 to 4,000 of whom were Greek (~13% Greeks). The Muslims lived within the walled part of the town while the Christian part of the population lived outside of the walls.8 In the next 50 years, the number of Greeks living in the town increased considerably. According to D.I Oiconomides, at the beginning of the 20th century, Trebizond consisted of 50,000 people, 15,000 of whom were Greek (30% Greeks).9 By 1910, the number of Greeks living in the province (vilayet) of Trebizond exceeded 200,000.

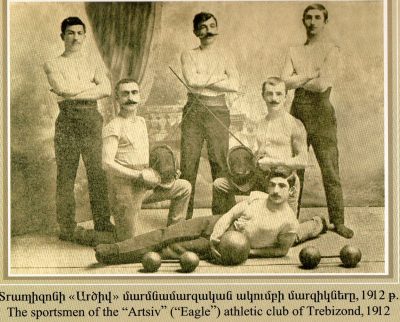

By the early part of the 20th century, the Greeks of Trebizond made up a part of the bourgeois. In many photos of the time, they were seen dressed lavishly; the men in tailor-made suits and the women in rich silk dresses. They were often seen traveling by carriage to their villas situated on the outskirts of the town.

The persecution of the Greeks of Trebizond followed the persecution of the Armenian population of the town. The Greeks of Trebizond were sent on death marches into the mountains of Bitlis around 1919-1920, most perishing never to return. The remainder were forcefully sent to Greece as part of forcible Exchange of Populations between Greece and Turkey (1923), thus ending an almost three thousand year presence of Hellenism in the region.

Today the region has a sizable community of Greek-speaking Muslims, most of whom are originally from the vicinity of Tonya and Of. They speak the Pontic dialect, a dialect which is based on the ancient Greek.

As Michael Meeker writes: “The Turks who settled along the Black Sea Coast of Asia Minor first encountered for the most part a Greek-speaking, not a Lazi speaking population, and the way of life which these Turks adopted was learned from Greek speakers.”10

Whereas the majority of Greeks were exterminated or forced out, Greek presence can still be felt in Trebizond today through its historic churches and buildings and the quasi Greek-Turkish culture which is evident through its people.

Administrator

References

- Labour Migration and Economic Conditions in Nineteenth Century Anatolia

Christopher Clay. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol 34, No.4. Turkey before and after Atatürk: Internal And External affairs. (Oct. 1998), pp. 1-32

2. The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism

3. The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism

4. Koromila, M.: The Greeks in the Black Sea, pp. 282-3

5. Labour Migration and Economic Conditions in Nineteenth-Century Anatolia

Author(s):Christopher Clay. Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 34, No. 4, Turkey before and after Atatürk: Internal and External Affairs (Oct., 1998), p. 7

6. Koromila, M.: The Greeks in the Black Sea, pp.282-3

7. Krikorian, Mesrob K.: Armenians in the service of the Ottoman Empire, 1860-1908, p. 51

8. Penny Encyclopedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain) Vol 25-26, p. 180

9. The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism

10. The Black Sea Turks: Some Aspects of Their Ethnic and Cultural Background. International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Oct., 1971), p. 332

Source: https://pontosworld.com/index.php/history/articles/245-the-greeks-of-trebizond-16th-20th-century

Destruction

Turkish reconquest 1918

Trebizond was seized by Russian forces on 18 April 1916, which temporarily saved the remaining Christians there. But encouraged by the internal disintegration and mass desertion of the Russian armed forces after the October Revolution, the Turks began to reconquer the eastern Black Sea coast and western Armenia in 1917/18. From January 1918, the Russians withdrew after negotiations. Turkish militias immediately launched an attack on the Greek community of Trebizond, which barricaded itself in parts of the city. On February 14, 1918, a squad of Turkish soldiers appeared, but they were unable to establish peace and order in the power vacuum. In the following two years, the security situation worsened even more. In Trebizond, massacres, eliticide and deportation to forced labor were repeated, similar to what had happened in 1915.

An Armenian news agency reported already on 17 March 1918 about anti-Christian excesses in Trebizond: “(…) that return of the Turks to Trebizond made itself felt in renewed acts of savagery. Thousands of Russian stragglers were shot or burned alive. Armenians were subjected to indescribable tortures; children were put into sacks and thrown into the sea. The old men and women were crucified and mutilated; all young girls and women were handed over to the Turks.” [11]

“At that time [July 1918] Dr. Crawford, a missionary, was stationed at Trebizond as Director of the American College. To him and his wife a large number of families turned, begging them to take care of their children during their absence. After strenuous efforts, he obtained permission from the Vali, Cemal Azmi. The parents paid the necessary amount for the support of their children, and even left their jewels in Dr. Crawford’s care. Dr. Crawford also tried to protect a number of young women by admitting them under the guise of teachers.

But, even in the American College, these children were not safe.

‘The whole town was terror-stricken. The Christians were in tears, and their cries resounded everywhere. Trebizond was a city of mourning. A crowd of breathless women was running about the streets, pursued by soldiers deaf to their prayers. The men had been torn from their homes and taken to a monastery called Astvazatzin. On the 13th of July, five days before the order for the deportation, all men who were Russian subjects and all the members of the Tashnaktzagan Committee were collected and placed on board a motor-boat, treated with great harshness, and told that they were to be taken to Sinope or Constantinople to be tried by courtmartial. All were men of position. Once well out to sea, they were thrown overboard and drowned. We learnt of their sad end when some days later we found about four hundred of their bodies on the seashore.’

This awful tragedy threw the inhabitants into a condition of indescribable terror. In their desperation some burnt their houses; others threw themselves into wells, and many committed suicide by jumping from roofs and windows. Not a few, some women among them, lost their reason. They knew, poor wretches, that their turn would come inevitably, and that they would be put to death without pity.”[12]

Alexandros Akritidis: Farewell Letter (1921)

The writer was a Pontic Greek from Lykast in the Kromni district, industrialist and mayor from Trebizond. He wrote to his wife one day before his execution:

My dear wife Klió! Today we attended mass and received Holy Communion, all of us, 150 people. Every day about sixty people are beheaded. Tomorrow it will be my turn… How many times I cried today! But who benefits from it? When you hear about my death, the world should not end for you. That’s the way fate has arranged it. Let the children play and dance. (…) May all forgive me: brothers, sisters-in-law and all relatives and friends! Let us hope that God will give us the opportunity to honor our wreaths. Farewell then! I am going to my father. Forgive me.

Excerpted from: Fotiadis, Konstantinos: The Genocide of the Greeks from Pontos. Vol. 2. Thessaloniki, 2004. Translated from the Greek: Lampros Savvidis

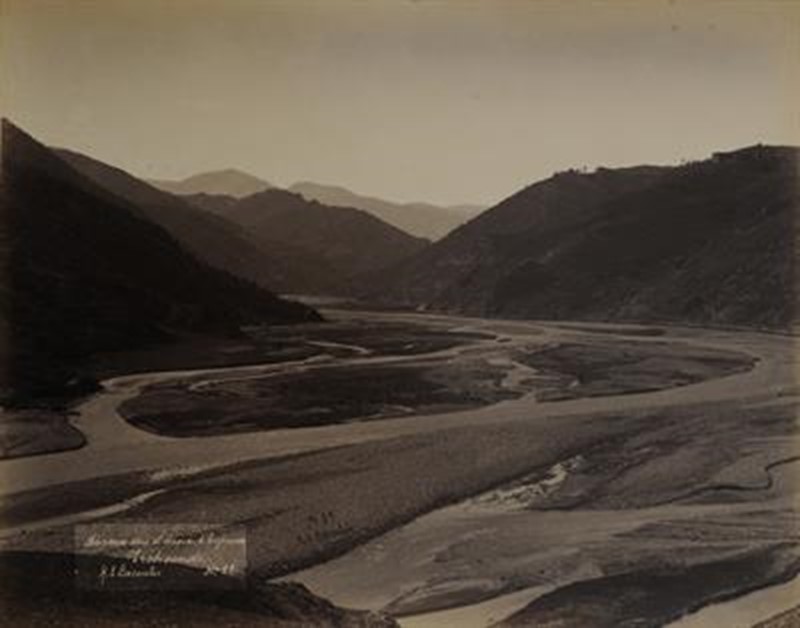

Matsouka – Ματσούκα / Matskas / Maçka

Matsouka (Grk: Ματσούκα – ‘club’, Trk: Maçka) is a region in the province of in Trebizond (Trabzon) in Turkey. Its capital is a town of the same name; Matsouka, otherwise known historically as Tzevislik (Grk: Τζεβισλίκ – ‘walnut’; Cevislik in Ottoman Turkish) and Dikaisimon in medieval Greek.

Matsouka is spread over the south of Trabzon, reaching up to the Zygana Pass (mountain) and the Kulat Dag. The region spans 60 km in length and 30 km in width. The Pyxite River runs directly through it. Prior to 1914, the region comprised 38,000 Greeks of which only 17,000 managed to flee to Greece following the forcible Greek-Turkish Exchange of Populations (1923). The remainder were either massacred by Turkish irregulars , died on death marches, or escaped to neighboring Southern Russia.

Matsouka was made up of 70 villages, 47 of which were purely Greek, 9 were mixed, and only 14 were Turkish. Combined with the villages of neighoring Santa, Matsouka made up the ecclesiastical province (diocese) of Rhodopolis, with Livera as its see. Three of the most prominent monasteries of Pontos; Soumela Monastery, Ioannis Prodromou of Bazelon , and Saint George Peristereota were all situated in Matsouka. Prior to 1903, these 3 monasteries were under the direct jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, until the Metropolis of Rhodopolis was formed.

During the rule of the Comnenes, Matsouka existed as an olbandok. Earlier it was a bandon of the Chaldian theme. Following the fall of Trebizond (1461), the Matsoukans didn’t adjust easily. In one report, on one particular Friday, Muslims were gathered at their mosques in Trebizond, and the Matsoukans entered the city armed, and at one stage took control of the centre of Trebizond.

From the mountain Thichis (Grk: Θήχης) in Matsouka, the Ten Thousand of Xenophon shouted ‘Thallatta Thallatta’ (The Sea, The Sea!) when they saw the Euxine (Pontus) Sea.

During the Byzantine period, the region was the base from which the Empire’s guards protected its eastern frontier. In the mountain ranges of Kulat Dag, Zygana, Thichis and Aeser lived the infamous Gabrades warriors and later the troupes of the Comnene Rulers. After the fall of Trebizond, many people fled the capital of Pontus and settled in Matsouka, thus increasing its population drastically. During the difficult period for the Christians (15-16th century), the residents were well behaved and disciplined, and large scale islamization didn’t occur in the region. Another reason for this phenomenon was the presence of the Sumela, Bazelon and Peristereota monasteries. Apart from these 3 (male-centric) monasteries, there were also 2 female functioning monasteries: the Monastery of Panagia Kremastis, and the Monastery of Saint John. Matsouka was also home to a further 64 Parish churches, and 225 chapels (both old and new). Just prior to the Exchange (1923), there were 3 philanthropic educational brotherhoods and 2 charitable brotherhoods in the region.

The majority of Matsoukans were cattle-breeders and farmers. Very few undertook more skilled labor. Migration was primarily to Russia and Constantinople, and the majority of those who immigrated did so to avoid being drafted into the army. Women were very active in cattle farming and work in general, especially keeping the mountain plains in good order.

Community Life

Each village had its own administration. Once a year, the men would meet at the village school and select a president for the village (the mukhtar; mayor), and also an administrative committee (the azathes). The notables of the village were responsible for collecting taxes and putting them to good use. The notables also had legal responsibilities such as solving matters relating to inheritance, as well as disciplining those who didn’t respect their decisions. They also selected the committees of the schools and churches.

Source: The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism. Malliaris Pedia. https://pontosworld.com/index.php/pontus/places/201-matsouka-macka

The Holy Monastery of Saint John Vazelon (Bazelone)

located about 40 km south of Trebizond in the district Maςka, close to the Sakhnoi and Kounaka villages, on a rock above the river Pyxites (Trk.: Altındere), it was consecrated around 270 after Christ in memory of St. John the Forerunner (Grk: Αγίου Ιωάννου Προδρόμου).

The actual monastery was built by Emperor Justinian in 565 and was used as a signal station against attacks by hostile mountain tribes. The monastery was connected to Trebizond by a paved path (royal road). In the course of time it was extended and restored many times. It formed the oldest and most prosperous monastery in the region. Probably with money from Vazelon the monastery Panagia Soumela was rebuilt after a fire in 640. The Vazelon monastery, which belonged to the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Rhodopolis has had a strong influence on the religious, cultural and economic development of the Pontos region.

After Emperor Justinian I ordered it to be repaired in 565 AD, the monastery has since renovated many times up to the present day. The current buildings date from the rebuilding in 1410. The interior of the monastery is adorned with a fine selection of paintings and iconography depicting various Christian events and Christian Saints. The frescoes on the north outer walls of the church of Heaven, Hell and the Last Judgement still bear their original beauty.

Dr. Ismail Köse, lecturer at the Karadeniz Technical University in Trabzon, describes the layout of the monastery as follows:

“The ground floor’s entrance, the windows and the doors of the monastery, which have an entrance in the west, are closed. As one climbs the stairs, she/he can see three rooms in each narrow corridor. There is a huge dining hall, kitchen and a large refectory. Next to these are three Byzantine basilicas and a vaulted cistern. In the ground floor of the monastery there are stairs marching up into a small hall. There are six rooms located in two sides of corridors. At the top of the Monastery there is church built in front of a cave.”

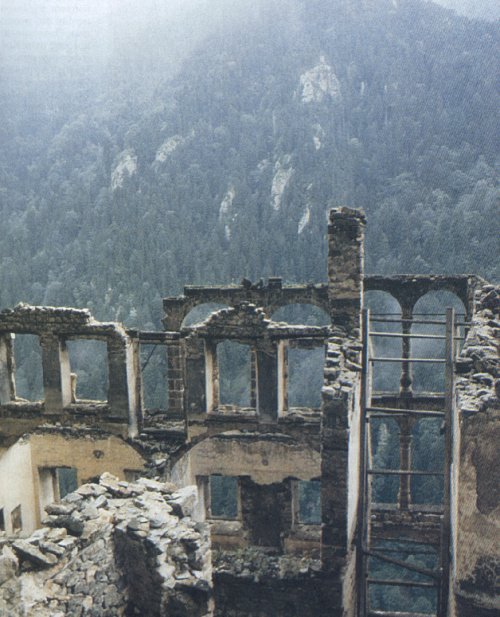

The monastery was attacked and ruined on numerous occasions by invading forces, mainly Persians and Turks. In 490 it was attacked and ruined by the Sassanid Persians, who also killed the 400 living at the monastery. During the Ottoman Turkish rule (1453–1922) the monastery was razed many times. In 1821 Chrysanthos, the Prior of the monastery, was able to avoid a general massacre of the 40 surrounding Christian villages via diplomatic means and the use of the monastery’s enormous wealth. In 1922 it was totally destroyed, leaving it in its current state of ruins.

The Vazelon Monastery was a refuge for hundreds of Pontos Greeks during the genocide in the First World War. 780 Greeks and 29 Armenians from the area as well as from Trebizond had fled there in 1915/6. In April 1916 the Ottoman military took over the monastery. Some of the refugees managed to save themselves, but 487 people were slaughtered, including the nuns from a nearby monastery. Fourteen girls were raped in the monastery before their murderers severed their breasts and heads.

Only one item remains from the monastery’s archives – the Records of Vazelon. It is now archived at the St. Petersburg Museum of History. Following its final destruction in 1922, the monastery’s last monk, Dionysios Amarantidis, saved the icon of Saint John the Forerunner, which he subsequently transported and guarded at the monastery of Agia Triada, located in Serres, Greece.

The monastery was abandoned in 1922 following the expulsion of the Greek population from Turkey.

The Destruction in April 1916

The Monastery of Bazelone was the centre of the tragedy. On 22 April 1916, the Turkish commander of the Kalpyer-Han [Kaloger-Hani?] post, situated at an hour’s distance, caused the monastery to be surrounded by gendarmes and soldiers. He ordered all who were in it – the monks plus 780 Greek refugees and 29 Armenian – to abandon the monastery in four hours’ time, and remove into the interior of the district of Arghyropolis [sic! Trk.: Gümüşhane]. A delegation of monks presented themselves to the Commander, and pointed out the wrong that would be done to the monastery if this order were carried out. He urged the inviolability ensured to the monastery by Imperial decree and finally begged of him to cancel the order.

The commander was adamant. He ordered that the forces should be reinforced by bands of irregulars, and that, if necessary, the evacuation of the monastery should be carried out by main force. After long deliberation, five monks and about 300 Christians evading the vigilance of the besiegers, contrived to escape and hide in the neighboring wood.

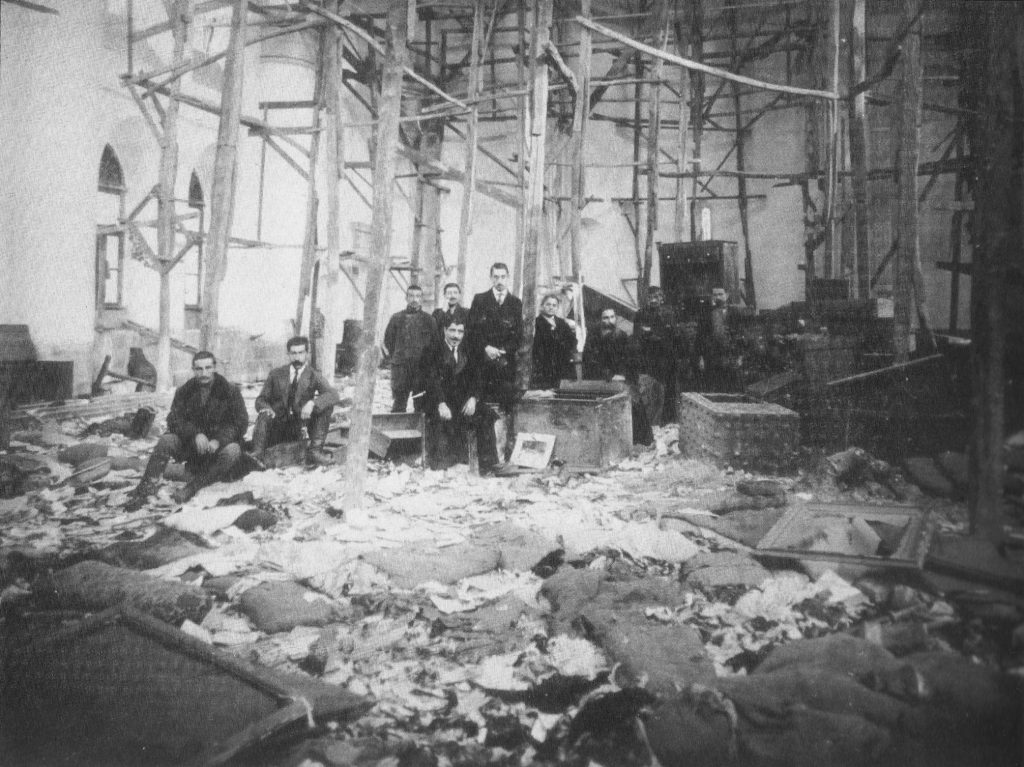

The next day, the remainder were conducted to the Ardache [Ardasa, in kaza Torul] (Chaldie) [Chaldia] district, under severe ill-treatment. No sooner was the monastery evacuated than the mussulman population entered it and started plundering. All the rich furniture it contained was carried away, all the treasure contained in it was plundered, its archives, bibles and manuscripts burnt to cinders. The Church was desecrated and destroyed.

They now converted the monastery into a place of massacres and outrages against women whom they found hiding in the forest and brought to the monastery, where the Turks first violated them, and then put them to death. Many men were also murdered. The following persons, natives of Thersa, were put to death in the monastery, Panayiotis Yordanoglou, George Yerinoglou, Pope Constantinos Papadopoulos, and his wife, Parthena, eighty years old, mother of Efstathios Karmahita, Patalina (seventy years), and Despina Tzironidou. The latter, who had escaped to the forest, was conducted to the monastery and violated by nine wretches in the presence of her companions. She was then put to death by the fiends.

Yordanoglou and George Yerinoglou were massacred. Their wives escaped while the criminals were asleep, and went over to the territory occupied by the Russians. Mr. Yordanoglou died from shock, Monk Nikiforos, and Panayiotis Paraskevopoulos with his relations, were mercilessly beaten and deported. After five days’ march, naked and half dead with hunger, they reached the district of Arghyropolis.

The nuns of the convent, situated at a short distance from the monastery of Bazelone, were also carried off as prisoners and met with a miserable end in exile.

The Metropolitan of R[h]odopolis, Monseigneur Cyril, wrote on 12 November 1918 the following:

“One shudders at the accounts given of the atrocities committed, and the number of victims. No less than 187 persons, who had hidden in the mountains, grottos, and subterraneous caves, were savagely massacred. Among these victims were fourteen young girls who had sought refuge in the monastery of Bazelone, where the Turks, after first violating these unfortunate creatures, mutilated them in a horrible way.”

After the breaking up of the Russian front, and the re-occupation of the Diocese by the Turkish Army, these monasteries [i.e. the ‘Stravropegiak’ monasteries of Panaghia Soumela and St. George Peristerata] began once more to feed the Christian population, and offer them, as far as lay in their power, protection against the aggression of the Turkish bands.

Quoted from: Ecumenical Patriarchate: Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey 1914-1918. Constantinople: Printed by The Hesperia Press, London, 1919, p. 110f. https://archive.org/details/persecutionofgre00consrich

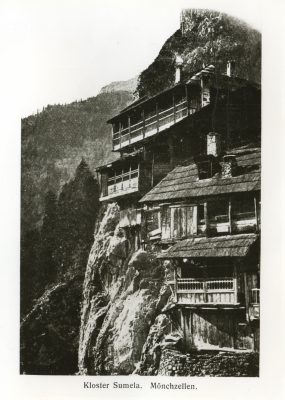

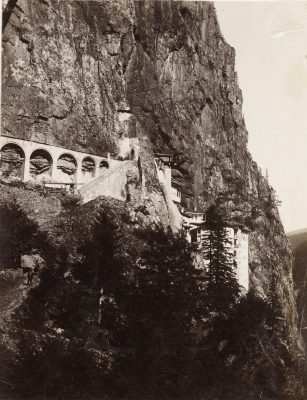

The Holy Monastery Panagia Soumela (Παναγια Σουμελα) – Panagia Soumeliotissa at Mount Mela

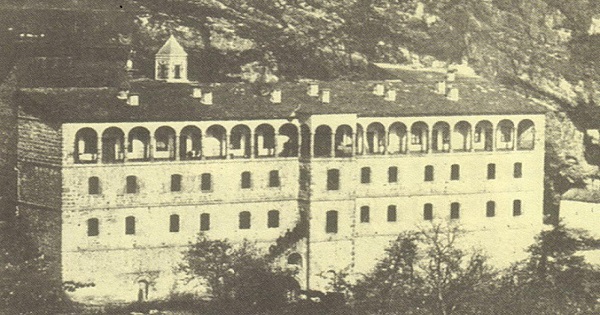

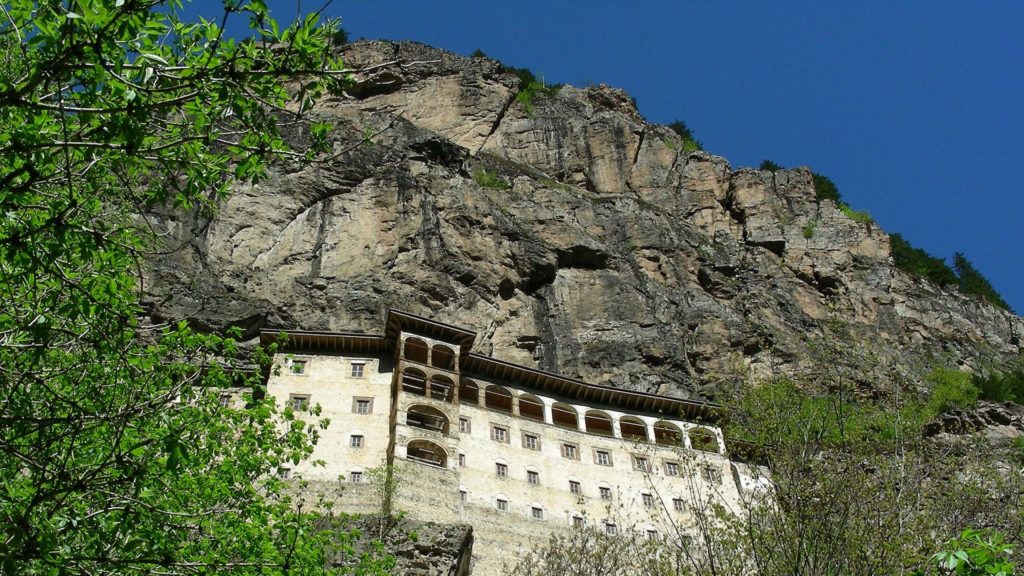

The shrine of Our Lady of Soumela (Gr: Παναγια Σουμελα – Panagia Soumela; Tr.: Sümela Manastιrι) is one of the most important pilgrimage sites of the Greek Orthodox Church. It is located about 45 kilometers south of the port city of Trabzon in the Altındere National Park in the narrow gorge of the river Pyxites (Tr.: Altındere) on a steep rock cliff at about 1200 m above sea level. The nickname ‘ Soumela’ is derived from the Greek word ‘melas’ (black), which refers to the mountain on which the monastery was built.

According to Byzantine tradition, the monastery was founded in the year 386 during the reign of the Roman Emperor Theodosios I (the Great), probably after early Christian hermits had settled on the site. The cave was extended and a chapel was built inside. Around 500 Emperor Anastasios I promoted the construction of a monastery, which was destroyed by fire in 640. The monk Christophoros from the Holy Monastery of Vazelon rebuilt it. In the 12th century it was destroyed again, allegedly by raiders in search of the icon, which was recovered unharmed from the river.

The oldest preserved buildings date from the Comnenian period. Here Alexios III (1338-1390) and his son Manuel III (r. 1390-1417) were crowned Emperor of Trebizond on 21 May 1350. Even after the conquest by the Ottomans in 1461, the monastery remained and developed into an important place of pilgrimage. It received its present appearance largely through new buildings and additions in the 19th century.

The sanctuary is located in a deep grotto. It is a natural niche, which is about 12 m deep and about 15 m high. The church dedicated to the Mother of God (Gr.: Theotokos) stands at the deepest point of the grotto. The most important sacred objects were kept here: an icon of the Mother of God (Theotokos) and a cross-reliquary with wood from the Cross of Jesus.

In the center of the complex there is a marble basin where the water dripping from the rock face is collected. This is considered holy water. Every first Sunday of the month the water was consecrated by the relic. This probably reflects a pre-Christian water and fertility ritual.

The icon of Panagia Soumeliotissa

The icon of Panagia Soumela is believed to be iconographed by the Evangelist Luke who was both a physician and an iconographer. According to tradition, whenever Luke drew icons of Panagia, the Holy Mother was very pleased and blessed his works.

Furthermore, she encouraged him to draw more icons. When Luke died, his disciple named Ananias took the icon and transferred it to the Church in Athens dedicated to Holy Mother of God. The icon was hence venerated as Panagia Athiniotissa.

Two Athenian monks were called by the Virgin to follow the Panagia Athiniotissa from the Church in Athens to Mount Mela in Pontos of Asia Minor. The monks’ names were Barnabas, and his acolyte Sophronios. At Mt. Mela, the icon was found at the end of the fourth century A.D. in a cave, and the monastery was built at this place to the glory of God. The icon was renamed ‘Panagia Soumela‘ (Holy Mother of God at Mela).

History

The monastery was inaugurated by the Bishop of Trapezunta in 386 AD, perhaps at an earlier place of Christian or even pagan worship. During the decline of the Byzantine Empire, the monastery was a center of education. The monastery was pillaged many times but was always rebuilt, with the latest construction occurring around 644 AD. Trapezunta was occupied by the Turks in 1461 and so was the monastery. Despite these difficult times, the monks remained in the monastery unshaken in their faith and tradition.

On 19 April 1916, after repeated raids and death threats on the part of the Turks, the holy fathers of Soumela had to abandon the monastery in the middle of the night. They crossed the front and were rescued in Livera. Panaretos, the abbot of the Holy Monastery of Vazelon, reported about the events at Soumela:

“Between April 9 and 19 [1916], regular and irregular [Ottoman] troops (…) repeatedly attacked the Holy Monastery of Soumela, demanding that the gates be opened and the monastery surrender to them. After the failure of the April 18 attack, they killed the monastery’s cart drivers and threatened to bring in heavy artillery to force their way in. Abandoned and unable to defend themselves, the monastery’s fathers fell into despair and decided to leave. Therefore, on the night of April 19, having hidden the monastery’s relics as well as they could and taking with them the holy icon of the Theotokos [Mother of God], which as tradition has it had been painted by the Apostle Luke, they left the monastery. Having crossed the dense forest unobserved by either side, they reached Livera—at the time occupied by the Russians—where they enjoyed the protection of the Metropolitan of Rhodopolis. On the next day, the Turks returned with reinforcements. Upon finding the monastery vacant, they occupied it and made it into a military outpost. Nevertheless, this monastery was not as unfortunate as that of Vazelon. The Arab commander did not allow it to be completely sacked. Silver oil lamps, bed-linen, carpets and all items necessary to the army during the war were, of course, taken, but complete disaster was avoided and digging in the foundations or the crypts was prohibited, as a result of which all the hidden relics were salvaged. (…).”[3]

In 1923, the remaining monks and nuns of the Pontos left their monasteries and convents for good. “The priceless libraries of institutions such as Panagia Soumela, Agios Ioannis Vazelon and Agios Georgios Peristereotas—which had been visited and consulted by many prominent scholars, including Jacob Philipp Fallmerayer (…)—were lost during the 1923 deportation, along with the ‘illustrated manuscripts and other holy relics which they were forbidden to take with them. The monastery buildings and surrounding facilities were ravaged by local Turks.’ Shortly before the uprooting, the monastic centres (where church fathers such as Basil the Great, Grigorios Theologos, and Ioannis Chrysostomos had lived lives of austerity, where the families of Komnenos, Gavras, Mourouzis and Ypsilantis had received their spiritual education, and—above all—where the spirit of the Pontian Greeks had been formed) succumbed to Turkish atrocities, and the desecration of holy places that marked the end of their long, glorious and outstanding history.”[4]

The monks of Panagia Soumela were forced to finally flee in 1923. They were not allowed to take any monastery artefacts with them. Therefore, they buried certain valuable and holy items in the front yard of the Church of St. Barbara which was built at a short distance of one kilometer from the monastery by Saint Sophronios. These items were the icon of Panagia Soumela, the handwritten Gospel copied on parchment by St. Christopher, and the Holy Cross with the honorable wood donated by Emperor Manuel Comnenos. This event took place in August of 1923.[5] A monk returned in secret in 1930 to retrieve the icon and take it to the then newly founded Panagia Soumela Monastery near Naousa in Greece.[6] According to another version the relics could be brought to Greece in 1931 on intervention of the Turkish Prime Minister Ismet Inönü. “Father Ambrosios, who was one of the monks of Panagia Soumela, was chosen by the Metropolitan Chrysanthos of Trapezunta to undertake this special journey. Father Ambrosios set out to go to Turkey on 22 October 1931. Upon arriving at the sacred site, Father Ambrosios was moved with tears. The laborious task of excavating began. Turkish soldiers and Greeks helped, including Father Ambrosios. Soon the hidden icon was unearthed along with the other sacred objects. They were all returned to Athens and deposited at the Benaki Museum in Athens for 20 years.”(7)

Today they are in the new foundation of the same name in the Greek city of Kastania, district of Veria (Macedonia) from 1951.

After the Soumela monastery was abandoned in 1923, it was used by tobacco smugglers. In 1961 it became the headquarters of a State Experimental Forest. The fact that Soumela survived was due to the efforts of Şükrü Köse, its first Chief Ranger. In the 1960s, Şükrü Köse held the key to the gate to Soumela and thus controlled access by tourists. In 1972, the monastery, still in ruins, was taken over by the Trabzon Museum.

Parts of the original monastery were destroyed in a fire in the 1930s and the site, including its famous Rock Chapel was looted and damaged by vandals. The monastery continued to deteriorate until 1972, when it was declared a national heritage site by the Turkish government and opened to visitors. The frescoes of the monastery are seriously damaged due to vandalism. The main subject of the frescoes are biblical scenes telling the story of Christ and the Virgin Mary.

Restoration and restrictions: The current situation

The restoration of the monastery began in the 1980s. During the 2015-2017 restoration works, a secret tunnel was discovered which lead to a place which is believed to have served as a temple or chapel for Christians. Also, unseen frescoes were discovered depicting heaven and hell as well as life and death.

For Orthodox Pontic Greeks the feast day of the Dormition of Mary on August 15 (old calendar) is the highest ecclesiastical feast day. At the request of the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and with the permission of the government of Recep Erdogan, the Patriarch celebrated Mass for the traditional Feast of the Dormition for the first time in 88 years on 15 August 2010. The permission has the character of an act of grace, which can be revoked at any time – “in case of bad conduct” – and has no legal character. Since 2016 no further masses have been held.

Due to an increase in rock falls, on 22 September 2015 the monastery was closed to the public for safety reasons for the duration of one year to resolve the problem; this was later extended to three years. It reopened to tourists 25 May 2019.

According to Milliyet, a Trabzon newspaper, Turkish academics have visited private collectors, museums and universities in Trabzon, Istanbul, Greece, Ireland, UK and US to collect information about artefacts that once had belonged to the monastery. The Turkish government is now demanding the return of 77 items from the property of the former monastery, mainly from Greece.[8]

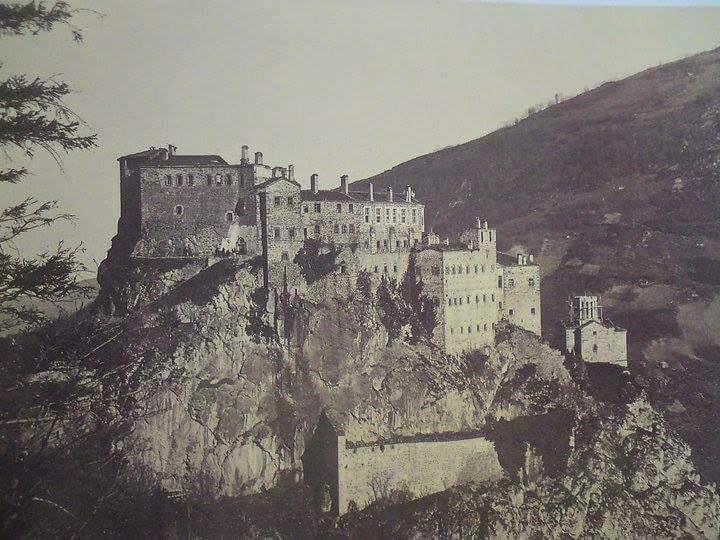

Holy Monastery of Saint George Peristereotas – Ιερά Μονή του Αγίου Γεωργίου Περιστερεώτα / Kuştul Monastery

Located near Şimşirli village in Maçka district, the monastery was founded in 752 at 30 km southeast of Trebizond. The name was derived from the monk Peristereotis (peristeri meaning pigeon in Greek).

Legend has it that a flock of pigeons descended from the forests of Sourmena and guided three monks who were carrying the icon of Saint George to the place where the monastery was built.

During its heyday the monastery consisted of 187 rooms/cells and a large library which housed over 7000 volumes of works. In 1203 and after 450 years of continuous use, the monastery was depopulated and for two centuries no monk lived within it. The monastery was abandoned after it was sacked by raiders.

In 1398 Emperor Manuel III of Trebizond granted permission for the monastery to reopen. Its abbots were then Theophanes of Lazia (1393-1426), Barnabas of Lazia (1426–49) and Methodios of Sourmaina (from 1449). In 1462 the monastery was partly destroyed when robbers and looters stole many of its heirlooms. Many of its possessions were also lost in the fires of 1483. In 1501 the monastery was placed under the immediate jurisdiction (stauropegic) of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, and remained so until its abandonment. It underwent restoration after it was damaged in a fire in 1904 or 1906.

During the First World War, the advancing Russian army occupied and rescued the Holy Monastery of Agios Georgios Peristereotas. In spring 1922, after the destruction of the Galiana (Galliani; Mesochori) district, the Kemalist authorities ordered the holy fathers of the local Holy Patriarchal Monastery of Agios Georgios Peristereotas to deliver all the sacred relics and other belongings of the monastery to them and move inland. The monastery council proposed paying to postpone compliance with the order, but the monastery did not have the amount of one thousand lire requested. Abbot Grigorios went to Trebizond, where he only managed to raise about seven hundred lire.

“On January 17, 1923, the monastery of Agios Georgios Peristereotas was evacuated:

‘A Turkish battalion which had arrived from Trapezounta under the command of Major Selaheddin, evicted the monastery’s staff forcefully in the evening, including the seriously ill hieromonk, Jeremiah of Peristereotas.

Christos, Jeremiah’s brother, and a friend of his undertook to carry Jeremiah on their backs to the village of Mandranoi, some 10 kilometres away. Due to formidable weather conditions, however, they were forced to leave the sick monk, covered, under a fir tree. When they went back for him the following day, they discovered that he had been eaten by wild animals.’

The Turks robbed the monasteries and convents of their money and ousted the monks and nuns. In Trebizond, the surviving monks boarded the ship Kios for their final trip to Greece after much hardship. The events of the last days of the Pontian monasteries are recounted in the memoirs of the Capuchin monk Cirillo Giovanni Zohrabian of Trebizond, who assisted the suffering Greeks in various ways during those critical years:

‘On February 2, [1923] the abbot and monks of the Orthodox monastery of Agios Georgios Peristereotas arrived. It was a miracle! Remembering the loot they had obtained from the monks, the Turks allowed them to occupy an abandoned room. I went to visit them.

‘The Lord’s wrath has turned on the sins of our people’, said the reverend abbot.

‘You are right’, I replied. ‘But now let us speak of more mundane matters. How can I be of assistance? What are your plans? Where would you like to go? Are you in need of money?’

For no apparent reason, the abbot began to weep. ‘Dear Father Cirillo’, he said, ‘look at what has become of us. If I were an unfeeling man, I would take your offer to be mockery, a Westerner deceiving Orthodoxy. When did we ever need to resort to you Westerners? Praise the Lord, but we deserve such humiliation for our sins’.

They wanted to go to a monastery in Kavala, and their relatives also wanted them to settle in that town. There were twenty-five monks, twelve adults and sixteen minors. I supplied them with clothes, blankets and food; I bought them their tickets, gave them eighty five Turkish lire, and took them aboard the Kios on February 7.’

The uprooting of the monks gave the local Muslims the opportunity to complete their destruction of the monastery of Agios Georgios. They not only looted the valuable works of art and sacred relics, they also took the doors and windows. During the turmoil, Cemal Eyuboğlu, an Islamized lawyer of high-class Greek descent from Mesochori (Galiana), piously removed the carved marble icon of Saint George ‘with his gold crown and gold bridal’ from the outer door of the old cloister to save it from desecration. He kept it in his house for forty years. In 1961, following extensive correspondence between Charalambos Kianchidis and Cemal Eyuboğlu, Konstantinos Ioannidis and Alexandros Polychronidis, both second generation Pontians, took the icon to Greece with the assistance of Nikolaos Kastanidis.”[9]

The monastery closed on January 17, 1923, when the monks and other Greek residents were expelled to Greece. A monastery with the same name was inaugurated on 16 June 16 1978, in Naousa, Imathia, which is where the monks of Kuştul Monastery are buried.

In 2005, the ruins of the abandoned monastery have been officially registered as a memorial monument thanks to Maçka Municipality’s application to Trabzon General Directorate of Cultural and Natural Heritage.

Efstathios Christoforidis (Sarpoglis): What our eyes have seen… The Mass Killing of Armenian Children near Farnavazu (Matsouka / Maçka)

In 1915 the Turks massacred the Armenians in their homeland. A million and a half. They spared no one. The army and the gendarmerie took them from the towns and villages to the roads leading to the mountains. On the march there, they separated all the men, killed them behind the hostels and then threw them into the rivers. Women and girls were dragged aside and desecrated from one hostel to the next. All the Turkish villagers rushed at them like rabid dogs. And they raped them, one by one, until they were finished. They did the same thing as they did with the girls, even with older male children. And finally they killed them.

That year we moved to Farnavazu[13]. That was our summer pasture near Kounaka(14). We were there together, my blessed grandmother, I and Panagiotis, the son of Nikolas the Black, and his wife. We all lived together in one house. We also grazed our cattle together. My grandmother and Panagiotis were cousins. Their fathers were brothers. We were one family. I was ten years old at the time. I looked after the animals with my aunt, Panagiotis’ wife. She sent me everywhere to make sure the animals didn’t cause any harm.

Once we saw them bringing a large convoy of Armenian children, about six hundred, from the road. They turned towards the mountain. There was a clearing opposite the houses, which we called Omalopa. It was now filled with seven to twelve or thirteen-year-old children. It was terribly loud. My poor people who were in the meadow were very frightened. They had never seen anything like it. They hid in the houses and barns and cried. Omalopa was full of children, surrounded by gendarmes who beat them with whips to calm them down. Then they sent two policemen to our mud hats. Uncle Panagiotis came from the direction where the police station was. He often went there to visit his friend, the sergeant. As soon as he saw the policemen going to the mud huts, he shouted out loud, “Where are you going?” They stopped and waited for him. He came closer and asked them what they wanted. They answered, “We need bread for these children you see there.” The uncle says: “Oh God, oh God, there are only seven or eight families here and we don’t have ten loaves of bread altogether. But you need hundreds.” They laughed and said, “Bring us five loaves and don’t worry. We’ll cut them up real small and throw them at them to keep them quiet.”

Uncle Panagiotis asked all the neighbors he met to bring bread and cheese and anything else they could find. Further up, in the gorge, was the village of the Pervanantes. All Turks. Only five or six families, but good people. They lived there all year round. The uncle also asked them to bring food and give it to the Armenian children.

Within an hour, the Pervanantes arrived, men and women, all loaded with baskets of bread and other things. After them came an old woman on a stick, crying.

Our people were even afraid to cry. A gendarme said to her: “Old woman, they are bringing the food for the Armenian children to feed them. But you, what are you doing here? Go back immediately!” The old woman replied: “I came here to get rid of something! I want to tell you and your master: Cursed be you, you wicked man, son of a donkey!” “Old woman”, the gendarme said to her, “be quiet, or I’ll do to you what I did to the Armenian woman. I killed her yesterday and threw her off the Pigaditsa[15] Bridge. Her basket is still there, by the side of the road. There’s a hen and her chicks in the basket. Go, take it with you and go home!” The old woman replied, “You go and take it to your mother, so she can run a decent household. For killing her you shall be cursed, and your father shall be cursed too!” Then he pounced on the old woman and wanted to cut off her head with his dagger. But Uncle Panagiotis intervened and begged him to leave her alone. And from the other side my grandmother and others went in between and grabbed the old woman.

My people and the Pervantes, who had gathered in the yard with the baskets full to the brim, took the policeman and left. They arrived in Omalopa. There the gendarmerie met them and took the baskets off their shoulders. They cut the loaves of bread into very small pieces and threw them to the children, just as one throws food to dogs. Within half an hour all the baskets were empty. They threw every empty basket to the side, and as soon as all the baskets were empty, a sergeant shouted, “Take your baskets and go to hell! And go to hell!”

The children threw themselves on the pieces of bread. Some choked, others stuffed their pockets with it, others cried, others screamed! It was horrible!

The next day the soldiers left, perhaps for Chapsi-Köy[16], loaded four mules with bread, came and, after having crushed the bread again, threw them at the children. The children threw themselves on the pieces of bread again and collected them. The older ones beat the younger ones, they also fought among each other. Crying, screaming, horrible! The soldiers looked on amused.

The clouds had cleared away, the sun was shining. The children had warmed up, they had also eaten something, and the older ones wanted to play the “slave children game”. They put up stones here and there, and next to them the smaller ones, and they talked in Armenian. ” Tsar, tsur…” Of the older children, some went on top, some on the bottom, and the younger ones beside the stones. They had to hold on to their trousers with one hand while running across from one stone to the next to catch those who had run down.

In the late afternoon we could see from our houses how a convoy came from the big street. They were about fifty people, men and children between ten and seventeen years old, as far as we could estimate. They were not very far away either. They were loaded with saddlebags. They were passing us on their way to the police station. On the other side, the soldiers and gendarmes had sorted out fifty children and brought them to the station as well. From there they left the main road and went into the forest, as one leads lambs. They took them to Samsora[17], in the middle of the dense forest, and before they reached the stream, they stopped. Around them were large pits, and the fir trees all around reached up into the sky.

Not even God could see anything in there … These pits were very deep. Not even grass could grow in them. They lowered the Armenian children into these pits, surrounded them, and then they called those who had come with the saddlebags. These were loaded with round stones from the stream. Immediately, the Kostorites[18], these run-down people with the dirty shoes and long underpants, surrounded the children. “Beat the infidels!” cried the soldiers and the people from here. And they opened their sacks and stoned the children like mad. The children’s heads sparkled… The screaming went up to the sky. But who was listening? And who was looking?

They struck without mercy. Eventually, the voices became quieter. These derelicts then went to the children’s pile, stripped them and took the clothes they were wearing. They left the children naked. The children had been very well dressed. Because the Armenians were wealthy. The Armenian women dressed their children with jackets made of thick woolen cloth, trousers, decorated vests, embroidered shirts, with caps and hats, with shoes, and they went off with them. The Turks had told the Armenians: “We’ll take you to Greater Armenia and we’ll make you a great empire.” The poor believed them. That’s why the old Armenian woman carried her hen with the chicks to the Pigaditsa bridge.

There was another one, a poor man, a weaver from Trapezounta. He had woven blankets for the horses. All our people, as far as they were carters, knew him. When the first convoy of Armenians arrived and stopped in front of the shops of Kounaka, our people saw him and went with him to the inn of Lazaroglou. He was loaded with a sack of balls of wool, still carrying the weaving comb and weaving tools under his armpits. “Where are you going?” they asked him. He replied, “We’re all going home to the Greater Armenia!” “What Armenia?” asked our people. “They will kill you.” “What are you saying?” he marveled. “Yes, last night, down at the inn, they killed twenty of you,” they told him. “What are you telling me? What am I going to do with this stuff?” He dropped the balls and the combs. There, at the end of the inn, near the door, was the stove. “Come,” our people said, “let’s hide you in the oven. When they’ve gone, and when it gets dark, we’ll take you to the village to give you shelter.” But he wouldn’t, and when the convoy left, he went out, mingled with the others and pushed forward. He went…

The mothers with their children also went as far as Chapsi-Köy. There they locked everyone in the hostels, the gendarmerie came in, separated them and took all the children. They gathered them in the street. A poor woman stood by the door of the inn and held her child, six, maybe seven years old, dressed, covered, her only child. She handed out a gold coin and wanted to give it to the gendarmes to spare her child. The gendarme kicked her, grabbed the gold coin and also grabbed the child, pulled its collar and threw it in the middle of the other children. The poor mother screamed: “My child, my child”. The gendarme pulled his knife and stabbed her…

All these children from the convoys that were moving towards the mountains were gathered and taken to Omalopa. The girls, they also brought them here. They desecrated and murdered them. They also stripped them of their clothes and took everything they wore.

The next day my aunt took the cows out to graze. She took me down to Arnolimn[19] so I wouldn’t have to see anyone. The gendarmerie and the soldiers sorted out another sixty or seventy children and took them to the pits down by the stream. In there they gathered the children. This time it was the Zyganites’[20] turn, loaded with sacks and stones. They could not see us.

But we heard their voices. “Strike the infidels!” The stones split the heads of the children. All of Samsora heard their cries. Before they finally died, the Zyganites went down to take the things from them, like the butcher takes the skin off the lamb, and they stuffed them into sacks.

After that we heard axe blows. They beat fir branches and covered the children with them. Then they took their sacks and went on their way. They went to dress their half-naked children, whose backsides were sticking out, with the clothes of Armenian children. On the way they said, “One day the Greeks will get their turn. “They’ll get the same treatment!” And they’d make jokes and sing…

Shortly afterwards we saw a gendarme coming out of the creek in our direction. We immediately left the animals and ran off, auntie first and I after them. The gendarme yelled: “You’ll never set foot here again!” We arrived home. The cows followed us… Why would we ever set foot down there again?

In the evening, Uncle Panagiotis came. He was bitter and said to his grandmother: “Parthena, there’s no God!” “Don’t say such things! That’s a sin!” replied granny. “What I say is true,” replied the uncle. “There is no God! Who ever saw little children being butchered, slaughtered with stones? Yesterday, the day before yesterday, and today, the Kostorites and Zyganites, the wretched, came upstairs packed with their clothes. They left them naked in the pits and covered them with branches! They went to clothe their own brats with them, to rejoice and celebrate. And you tell me that there is a God. Ah, poor Parthena, they’ll do the same to us soon. Our God has forgotten us…”

The uncle stayed sitting for a moment, then suddenly he stood up and said: “You, it must not be like this, stoning little children, taking their clothes off and taking them with you! The wicked! And those poor children! With their beautiful dresses, caps, jackets and shoes… At their necks they still wore talismans and jewellery. They looked like flowers! And to this day, the children of the Kostorites had never worn shoes, they walked around barefoot, but now they wore shoes!”

In the evening, everyone from the neighbourhood gathered at our place. Uncle Panagiotis told them, and they cried. No one wanted to eat. They came back from work hungry. No one had seen or heard anything like this before… All these children, within a week they had taken them here and killed them with stones. Exterminated.

Sixty-eight years have passed since then. Time passed without complaint… a year later it was our turn. We could not return to Farnavazou.

Those heads of the little children, I tell you, are still there, lying in the pits of Samsora. They scream: “Come and get us!”

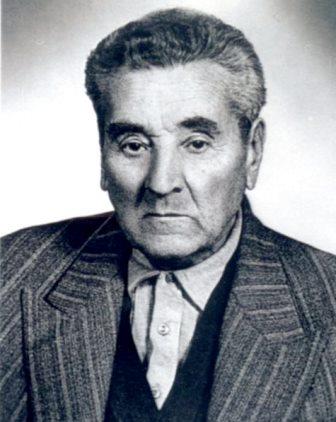

About the eyewitness

Efstathios Christoforidis (Sarpoglis) was born in 1905 in Kounaka, Trapezounta (Turkish Trabzon; today Bağışlı). The pseudonym Sarpoglis comes from the word sarpin = wood grain store.

After the genocide and the forced population exchange (Treaty of Lausanne 1923) E. Christoforidis lived in Xirolimni, Kozani, Greece, where he died in 1984. At the age of 10, he experienced a tragedy in his Pontic homeland, which brought him to his new home in 1923.

One year before his death and 68 years after the events, he managed to overcome the trauma of 1915 to the point where he was able to record his memories in his Pontic maternal dialect (Pontiaka). His book Black Times and Black Day – the Birthplace of Kounaka (1983) contains among other things the brutal murder of six hundred Armenian children.

This traumatic event haunted E. Christoforidis throughout his life. His children said: “Our father never slept through till morning” because “the heads of the Armenian children are waiting for me“, as he explained to his family.

His text was first translated into the New Greek vernacular (Dimotiki) by Jordanis Pampoukis in 1986 and ‘refreshed’ after 32 years by Stathis Taxidis in 2018.

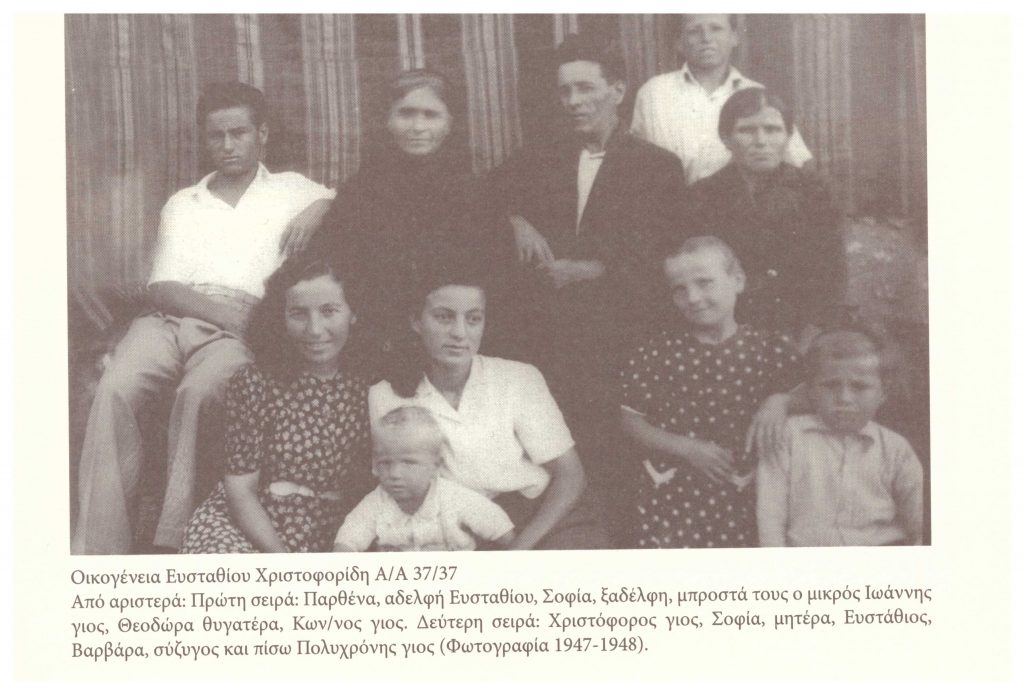

Efstathios Christoforidis had five children: Christoforos, Polychronis, Theodora, Konstantinos and Ioannis.