In the first half of the 16th century, Hamshen (Trk.: Hemşin) was under Ottoman rule. A manuscript copied in 1531 informs us that Armenian boys were taken for the devşirme (child levy) from ‘Trebizond, Hamshen, Sper and Baberd… to the shores of the lake of Van, and who can describe the misery and tragedy of the parents’.[1] At least until the midst of the 17th century, Hemshin (Arm.: Hamshen) was an Ottoman border district, presumably with unconsolidated power.

Hamshen / Hemşin People of Armenian origin

According to a 2005 international conference, the overall figure of this diverse ethno-linguistic group of people (Trk.: Hemşinliler; Arm.: Համշենցիներ, Hamshentsiner), also known as Hemshinli, Hamshenis, Homshetsi (also Hamshetsi) and Hamshil, was given as high as 400,000, half of them being Sunni Muslims, while the others remained Christian or reversed to Christianity; of these, up to 200,000 live inside Turkey.[2] A more recent expert estimate, published in 2017, mentions “30-35 thousand Armenian speaking Hamshen (Hopa-Hamshen), who speak their own dialect, and about 200 thousand Turkish speaking Hamshen” in Turkey.[3]

The Hamshen people today can be divided into three main groups: The Christian Armenian Hamshentsiner, who live in Abkhazia and Russia’s Krasnodar District. They speak the Hamshen Armenian dialect; the Sunni Muslim Armenian-speaking Hopa-Hamshens, who live in the Hopa and Borçka regions of Artvin and call themselves Hamshetsi or Homshetsi; and Sunni Muslim Turkish-speaking Hamshens (Bash / Baş-Hamshens) who mostly live in the Turkish province of Rize and call themselves Hamshil.[4]

History

The isolated Armenian Hamshen community in a non-Armenian – Laz and Greek – environment goes back to the late 8th century when a part of the Armenian nobility rebelled against the harsh treatment by the Arab invaders and had subsequently to emigrate, including the Amatowni leader prince Šabowh Amatowni (Shabuh Amatuni), his son Hamam and 12,000 followers. They were given the town of Tambur in the mountains south of Rhizaion (Trk.: Rize), where they founded a new principality in the Byzantium-controlled mountains of Pontos. Tambur was then burnt by Hamam’s brother-in-law, the Georgian prince Vašdean, and the new city that was reconstructed at the same place was called Hamamashen (‘Built by Hamam’) after Hamam Amatowni.

Islamization

Ottoman records show that Hamshen Armenians remained overwhelmingly Christian until the late 1620s. Islamization seems to have taken place gradually, mainly as a result of the need for equality with Laz Muslim neighbours, the desire to avoid the oppressive taxation of non-Muslims, increasing Ottoman intolerance of non-Muslims in a period of weakness for the Ottoman Empire, and anarchy caused by semi-autonomous local Muslim rulers, or ‘valley lords’ (dere-beys). Islam took root in the coastal areas first, and then advanced to the highlands. Emigration of Armenians also took place during this period of pressure, from the 1630s to the 1850s, though fugitives who fled to other parts of the Pontos were still often forced to convert to Islam.

Conversion to Islam in Hamshen led to divided families, in which typically house-bound mothers persevered with Christianity, while men with their more frequent external contacts became Muslim. In addition, there emerged a segment of crypto-Christians called gesges (in Armenian ‘kes-kes’ – half-half). These Hamshen Armenians privately kept practicing various Christian and pre-Christian customs, in particular the custom of popular pre-Christian feast days such as Vardavar[5], even sometimes including their attendance of church services. In difference to Pontian Greek crypto-Christians[6], who still have a visible presence in the Trebizond region and beyond, the Hamshen crypto-Christians had disappeared by the end of the 19th century, for two reasons: During the liberal Ottoman Tanzimat (reform) period (1839-1876) with its proclamation of religious equality some Muslim Hamshenlis felt encouraged to revert. Reversion to Christianity, however, caused intensified Muslim mission and led to the opening of Turkish schools in the area and increased linguistic Turkification.

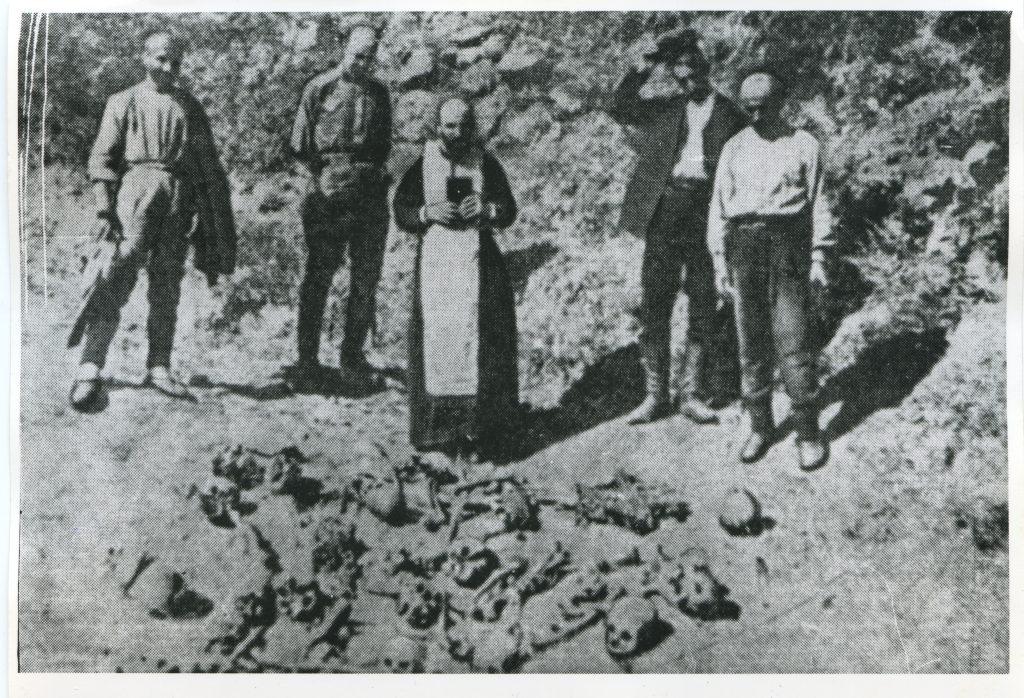

Relations between Muslim Hemşinliler and Christian Armenians in the region were sometimes uneven. In Khotorjur (Trk.: Hodoçur), the neighbouring area in the south, Muslims of Hamshen were hired by the Catholic Armenians as guides for travellers, guards, and seasonal workers. Despite these generally friendly relations, some Hamshen Muslims who engaged in banditry also periodically attacked the Khotorjur Catholic Armenians. During the genocide of 1915, some Hemşinliler and other Muslims of Armenian descent used the opportunity to rob their Christian Armenian neighbours and took over their properties. The last Christian Armenian village in Hamshen, Eghiovit (Elevit), was destroyed, with its population deported and killed. After the First World War, Khotorjur was partially repopulated by Hemşinliler. In Hopa and more particularly in Karadere Valley and regions closer to Trebizond, Islamisized Armenians helped Christians instead of robbing them.

Language

Initiatally, the gradually Islamized Christian minorities of the Black Sea littoral and its hinterland – Pontian Greeks and Armenians from Hamshen – were well preserving their distinct Greek (Pontiaká) and Armenian dialects (Homshetsma or Hemşinçe in the Western sub-dialect, Homşenc‘i lizu in the Eastern and hyeren in the Northern sub-dialect).

As to the Hamshen dialect, the crisis started when in the 19th century Turkish school education was intensified in the area between Rize and Hopa, in order to foster Muslim counter-mission there.[7] The pressure exerted by local authorities, combined with new opportunities of economic and social advancement in Muslim Ottoman society led to the loss of the ability to speak the Armenian language for most Hamshen Armenians. However, Armenian still continued to influence the type of Turkish spoken by the Hamshenlis through vocabulary, phrase structure, and accent.[8]

Together with Pontic Greek and the Laz language, the UNESCO classified the Armenian dialect of the Hamshen people of the Black Sea as one of the 18 languages under the threat of disappearance in Turkey, according to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in danger. Currently, the Hamshen dialect is classified as ‘Definitely endangered’. The report does not mention the number of Homshetsma speakers.[9]

Music

Identity Issues

The Muslim Hamshenlis developed their own unique group identity, and managed to maintain it till present times. In public, most Hemşinliler reject an Armenian origin, and some even insist they were descended from Turks from Central Asia who allegedly founded the ‘Gregorian’ (Armenian-Apostolic) denomination of Christianity. They resent Lazes and others who call them – usually insultingly – Armenians. This may be a result of the experience of persecution and destruction during and after WW1, when some Muslim Hemşinliler were mistaken for Armenians because of their Armenian language and killed.

Unlike Armenian converts in other regions, there were no recorded instances of reversion to Christianity among the Islamized Armenians and Greeks of Hamshen or Pontos during the Russian occupation of the area from 1916 to 1918. But abroad Christian Hamshenlis can be found, in particular in the Krasnodar region of the Russian Federation and in Abkhazia, where nearly all Hamshen Armenians adhere to the Armenian Apostolic Church. Their presence in Abkhazia goes back to Tsarist nationalities and religious policies of the 19th century, when after the successful oppression of Northern Caucasian resistance to Russian conquest during 1864-1878 the Russian Empire tried to alter the ethnic and religious composition of the population by increasing the Christian share. While most Muslim Abkhazians and other Northern Caucasian ethnic groups were expelled and fled their destroyed villages during the muhajiroba[10], seeking refuge in the neighbouring Ottoman Empire as the self-proclaimed protector of Russian Muslims, Russia transferred Ottoman Christians – Pontos Greeks and Hamshen Armenians – from the southern Black Sea region to Abkhazia, with the result that the Abkhazian titular nation found itself in a minority position already one hundred years after the Russian conquest of Abkhazia 1810-1829.

The case of the Christian Hamshenlis of Abkhazia is indicative for the competition of self-identifiers in the Hamshenlis’ identity: Hamshen can be used as a synonym for all Muslims from a certain region, even without the notion of Armenianness, or as a synonym for Islamized Armenians from this particular area, or as a synonym for all ethnic Armenians from Hamshen, not regarding their religious affiliation. There is also the option of identifying the Hamshenlis as an ethnos in its own right, as the website Hamshenian Forum suggests.[11]

The current Armenian interest in the Hamshen ethnos or sub-ethnos seems to be caused by the specifics of this ethno-religious group. In its understanding as a regional Armenian identity of the Black Sea Region the Hamshen case not only questions any limitation of Armenianness to the religious constituent of identity, but has the ‘modern’ capacity to bridge the traditional gulf between Muslim and Christian identities. (…)

In modern industrial or post-industrial societies, identities are a matter of personal, individual choice and at the same time a response to given circumstances. In Turkey, dual identities with their ‘bridging’ capacities seem to be highly relevant after compulsory mono-ethnization and modernization, – often at the expenses of local and regional peculiarities and massive estrangement. Many Turkish nationals from the Muslim majority are currently in search of their family’s ethnic and cultural roots, which some may discover in their Hamshen or otherwise Armenian heritage. Although most Armenians continue to identify Armenianness with the affiliation to the Armenian Apostolic Church or at least to Christianity, they are now confronted with the fact that part of their nation was compelled to embrace Islam and stayed with this decision.

Sergey Vardanyan: The Number of Hemshil (Hamshen) Muslims Living in Turkey

Due to the existing ban over the decades the Armenian intellectuals and academics living in Turkey have not had the opportunity to openly speak about the Armenian genocide and one of its consequences: the forced conversion to Islam. In Soviet Union and in Armenia as well, this topic was not being discussed further and only starting 1980 several publications have more or less mentioned about the forcibly Islamized Armenians, in particular Hamshens.

The numerous publications of the Armenian and Turkish press about the Armenians, who were forcibly converted to the Mohammedan faith made in recent years, are unfortunately very late because the silence of several decades has caused irrecoverable losses.

Many people, who had changed their religion but had retained their Armenian language and the memory of their origin, were out of touch with the Armenians of Armenia and Georgia due to closed border between the USSR and Turkey and thereby they had forgotten their native language and had distanced themselves from their roots. During this time, Turkish propaganda did its dirty deed: it created a negative image of the Armenian people, falsifying the history of Islamized Armenians.

The Armenian priesthood of Turkey, deprived of all rights, could not help its compatriots; forcibly Islamized Armenians who lived in provinces and were scattered over distant mountain villages. On May 30, 2007 the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople His Holiness archbishop Mesrop Mutafyan during a meeting with the delegation of congressmen from the USA reminded that 1.5 million Armenians were killed during the genocide, noting “We should not forget that a large number of Armenians adopted Islam to avoid mass deportation. We consider them our people because despite converting to another religion they continue to speak Armenian and adhere to the Armenian culture.”

It appears that the words of Patriarch apply to the Hamshen Armenians as well, forcibly converted into Islam in the 18th century in the Hamshen region, who were forced out of there and today they live far away from their homeland but were able to preserve the Armenian language.

And what is their number in Turkey at the beginning of the 21st century?

Although the Turkish authorities formally display that only Turks live in the country, in fact they are very concerned inside and are trying to gain insight into the puzzle of people living in Turkey. On the orders of the National Council of State Security in 2000 the scientists from the following universities – Erciyes (Kayseri), after Inönü (Malatya) and Fırat (Elazığ-Kharberd) studied the ethnic minorities of Turkey and made up a report where along with 60 thousand Armenians, 12.6 million Kurds, 870 thousand Arabs, 80 thousand Lazi, 2.5 thousand Circassians, 1 million Georgians there were also 13 thousand Hamshens living in Rize and Artvin. We are uncertain as to under which principle this census was conducted, but the fact is that according to the Armenian newspaper ‘Agos’ of June 13, 2008, these figures were presented to the National Security Council in Istanbul.

According to our research the number of Hamshen, including the Armenian speakers is much higher. They mainly live in the town of Hopa, in Artvin province and in the regions. The locals say that half or even more than half of the residents of Hopa are Armenian speaking Hamshen. In 2015, 19 thousand 748 people lived in Hopa and approximately 10-11 thousand of them were Hamshen. The proof of the increase of their number is that since 1922 out of 15 alternating mayors two – Yilmaz Topaloğlu (2004–2009) and Nadim Cihan (elected in 2014) are Hamshen.

As per the data of 2015 15 thousand 104 people lived in the regional villages of Hopa. According to our research there are more than twenty villages and countries in the province where Hamshen live, part of which administratively subordinate to the regional center Kemalpaşa (former Makrial). The Lazi live in seven villages of the province. And again, according to the locals the number of Hamshen among the rural residents is prevailing. We believe that their number surmounts 8 thousand.

Summing up we can affirm that in the province of Hopa, in the region of Artvin more than half – about 18-20 thousand (maybe a little more) out of 34 thousand 852 residents (2015) – are Hamshen. To confirm our assumptions for the first time we present the comprehensive list of places of residence of Hamshen in Hopa compiled by us which had been added to and verified during the last years of our visits. Their old names and variants used by the locals are also shown in brackets.

- Balıklı (Zendid), 2. Başoba (Khigi, Khigoba), 3. Güneşli (Dzagrina, Zargina), 4. Eşmekaya (Veyi Ardala), 5. Hendek (Gardji), 6. Yoldere (Zurbidji), 7. Çavuşlu (Chavushin), 8. Chimenli (Vayi Ardala), 9. Pnarl (Anchiog, Anchorokh), 10. Koyuncular (Zaluna, Zalona) and also Kemalpaşa town (Makrial) and all the villages included in its administrative district, 12. Akdere (Choli ked, Medogum ked), 13. Gümüşdere (Helu ked), 14. Chamurlu (Chanchakhana, Chanchagon), 15. Üçkardeş, 16. Kazimie (Veyi Sarp), 17. Karaosmaniye (Hedzelon, Hetselan), 18. Keprudju, 19. Osmaniye (Keshogtsets ked, Keshoglinoun ked), 20. Halbaşi, Halbaş, 21. Şana, 22. Chagmagin, 23. Papat.

As per the official Turkish statistics in 1990 2 thousand 658, in 2000 – 4 thousand 124, in 2007 – 4 thousand 597, 2008 – 4 thousand 519, in 2009 – 4 thousand 480, in 2010 – 4 thousand 794, in 2011 – 4 thousand 894, in 2012 – 4 thousand 942, in 2013 – 5 thousand 216, in 2014 – 5 thousand 182, in 2015 – 5 thousand 176 people lived in Kemalpaşa (Makriali).

Almost 3 thousand Islamized but Armenian speaking Hamshen live in the Artvin province, Borçka region (population in 2007: 24 thousand 133, in 2015 – 22 thousand 293 people), in the town of Borçka (in 2015 – 10 thousand 864 people) and in villages Çiftekeprü (Chkhala), Chayli (Beylivan, Beglevan, Baglivon) and Yeşilköy (Manastir).

Thus, the total amount of residents in the province of Artvin in 2015 was 168 thousand 370 people, as per our approximate estimates 24–25 thousand Armenian speaking Hamshens live there, including 22–23 thousand in the Hopa and Borçka regions, 1–2 thousand (or a little less) are scattered around the province. According to our data in the village of Achmabash of Sakaria province they also understand the Hamshen dialect of Hopa, although in everyday life the middle and the new generation prefer to communicate in Turkish.

Today there are several villages of Hamshen-Muslims in the towns of Karasu and Koçali in the Artvin region and also in the region of Akçakoca of the neighboring Düzce province: Paral (mainly Baş-Hemshil, there are also Hopa-Hemshil, they have settled in the former Greek village of 1930’s, there is a Greek church there), Kestanepnar, Aktaş, Karapelit, Yenidağ (now Ortaköy), Lahana, Karatavuk, Yenidje, Hemşin (now Armutlu) and Gegam (now Kovukpelit) which used to be inhabited by Christian Hemshils. The middle and the new generation of these villages speak Turkish, although they understand the dialect of Hopa. According to the inhabitants of the neighboring villages (the representatives of other nationalities) living in the abovementioned villages, Hamshen are called ‘Ermeni’ (Armenians). And how many Turkish speaking Hamshen live in the Rize province, where the historical province of Hamamashen-Hamshen was once located and is currently divided into five regions: Hemşin, Chamlikhemshin, Fındıklı, Igizdere, Çaylı, Pazar, Ardeşen. As per 2015 data 328 thousand 979 people lived in the province of Rize, from which 215 thousand 596 people are urban residents and 113 thousand 383 people live in the village. According to our inquiries every third or fourth person in different villages of the province is Hamshen, although not everyone accepts his or her Armenian roots. There are many supporters of left-wing political beliefs, Marxists, a large number of radical Islamists and grey wolves among the Hamshen of this province. Most likely the amount of Turkish speaking Hamshen is about 80–100 thousand. Since the flow of people from the villages to the cities is very large, one may assume that approximately the same amount of Hamshen live in Istanbul, Ankara, Bursa, Izmir and other provinces of Turkey.

The Turkish speaking Hamshen live in the Trabzon province; (population as of 2013 – 758 thousand 237 people) in Arakla, Sürmene, and other regions. Due to lack of material resources we could not do the same kind of work in Trabzon, hence we cannot say anything about the amount of Hamshen living there.

We managed to find out that there are fourteen villages in the Erzurum province, where Turkish speaking Hamshen live. We were able to visit two villages. According to our surveys one could notice that estrangement is at its highest in these fourteen villages: people hardly remember Armenian language. As we were not able to visit all the villages, we cannot say anything about the Hamshen of Erzurum.

To sum up as per our research data 30-35 thousand Armenian speaking Hamshen (Hopa-Hamshen) who speak their own dialect and about 200 thousand Turkish speaking Hamshen live in Turkey. To reconfirm the real amount of Hemshil living in Turkey, researches need to be implemented in the provinces of Artvin, Rize, Trabzon, Erzurum, Düzce and Sakarya, also in Istanbul and other towns, but it requires material resources. Therefore we turn to our compatriots to assist in this matter. Alongside with the study of the number of Hamshen, ethnographic, folkloristic, dialectological studies will be implemented, as well as surveys of villages, houses, household items and work tools, songs and dances of peasants, musicians, all the speakers will be sound recorded. High quality devices for sound recording, video recording and photographing are needed to implement the abovementioned. As to the Muslim Armenians, their number according to the press and television ranges from 2 to 5 million people, but we think that these figures today are not scientifically proven and it is unknown whether there are more or less Islamized Armenians, as these numbers were disclosed without taking into account the standards adopted in science, without reliable ethnographic, dialectological, genealogical database of the inhabitants of provinces, regions, cities and villages.

“Dzayn Hamshenakan”, March-April 2017

English translation published in “Armat: National platforms”, 10 January 2019, https://armat.im/en/publication/1547074197

Further information:

https://bantuhd.blogspot.com/2020/09/700.html?view=timeslide